Last updated: November 18, 2019

Article

An Increase in Fires for Lake Clark

NPS photo/E. Rupp

Read more!

McKinley Fire

Read more!

Swan Lake FireThere are three fuels thought to be the most important for understanding fire danger in boreal and temperate forests: Litter, measured as a Fine Fuel Moisture Code/FFMC, the loose duff material, measured as the Duff Moisture Code/DMC, and deep, compacted organic fuels or Drought Code/DC. For the park and preserve, when the duff moisture code, a measure of the moisture content just below the green moss that covers much of the forest floor, is at or above 60 DMC (moisture content of 72.9%) it is a pretty good indicator that fire can smolder overnight in the duff material. When DMCs reach 20 and higher there is greater potential for lightning ignitions.

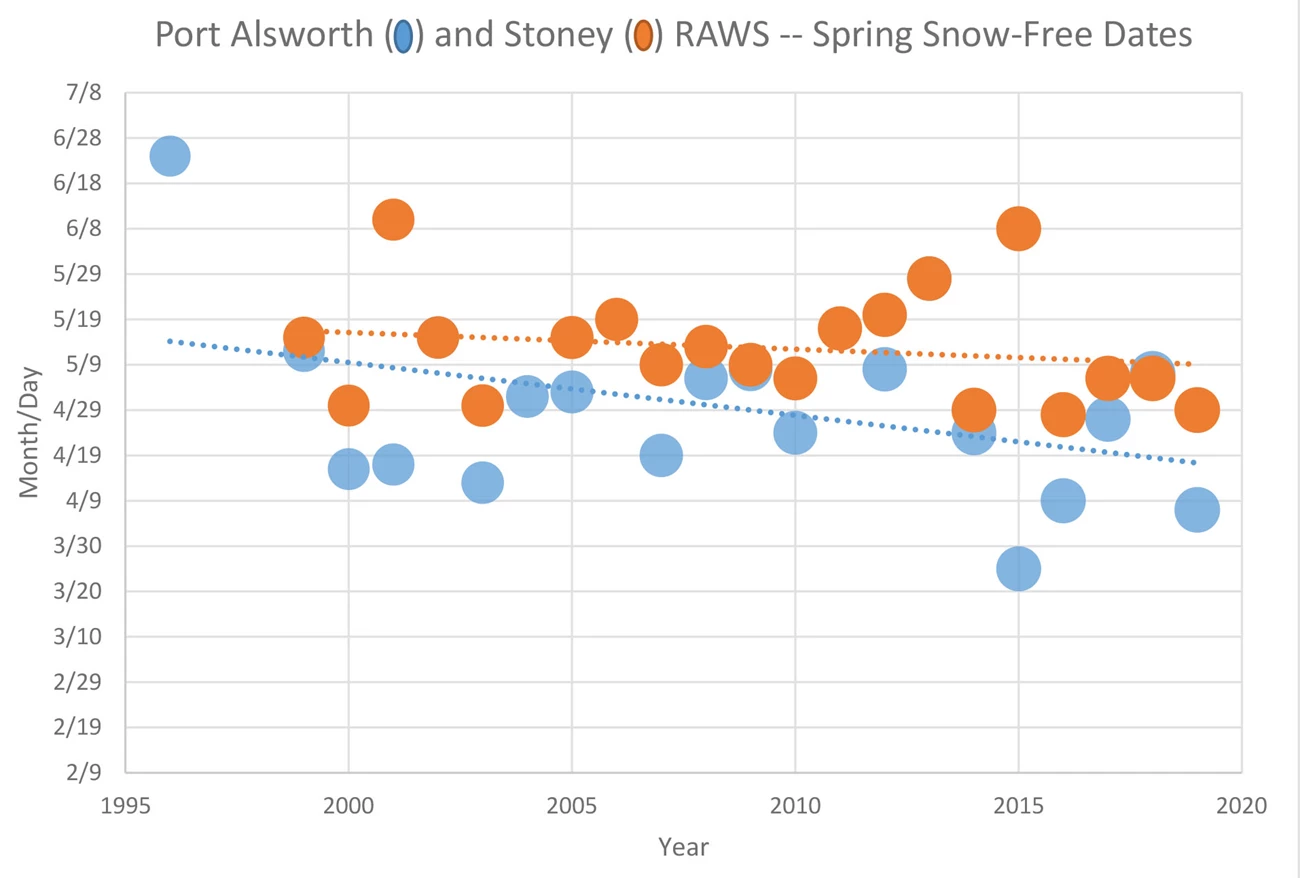

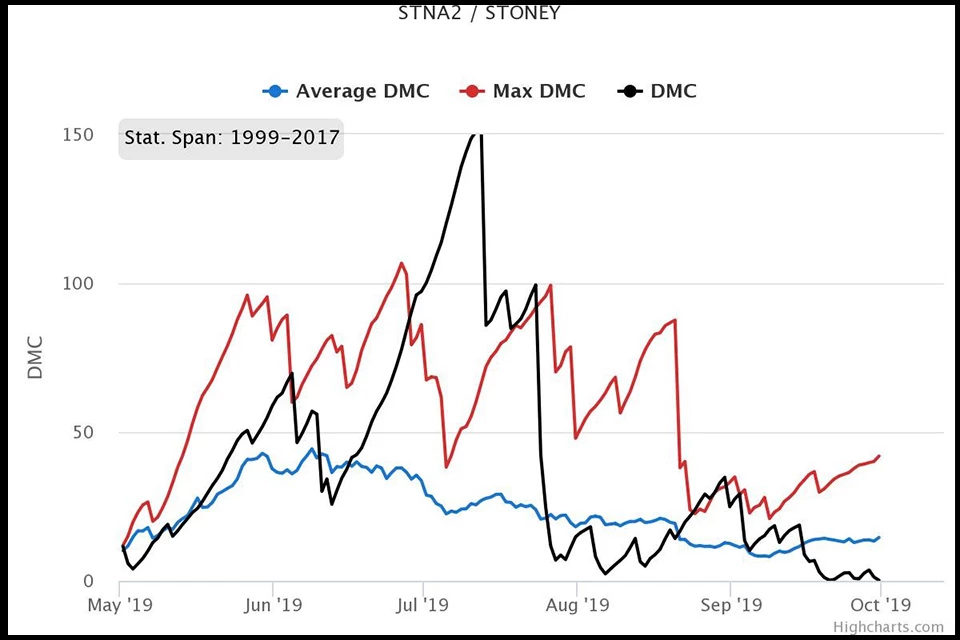

By June 1 of this year, the Stoney RAWS reached a DMC of 61 and by June 11, the Port Alsworth RAWS reached a DMC of 62 and the first wildfire in LACL, Round House Mountain, was discovered. Based on the location (proximately of identified values to be protected) of the wildfire and the time of the season (the potential that the fire could negatively impact multiple sensitive resources over time) the fire was suppressed by Mat-Su/Southwest Area Forestry and declared out on June 13 at 2 acres.

On June 12, two fires were discovered west of LACL along the Chulitna River, near Long Lake. Both fires were suppressed with suppression resources within a couple of days.

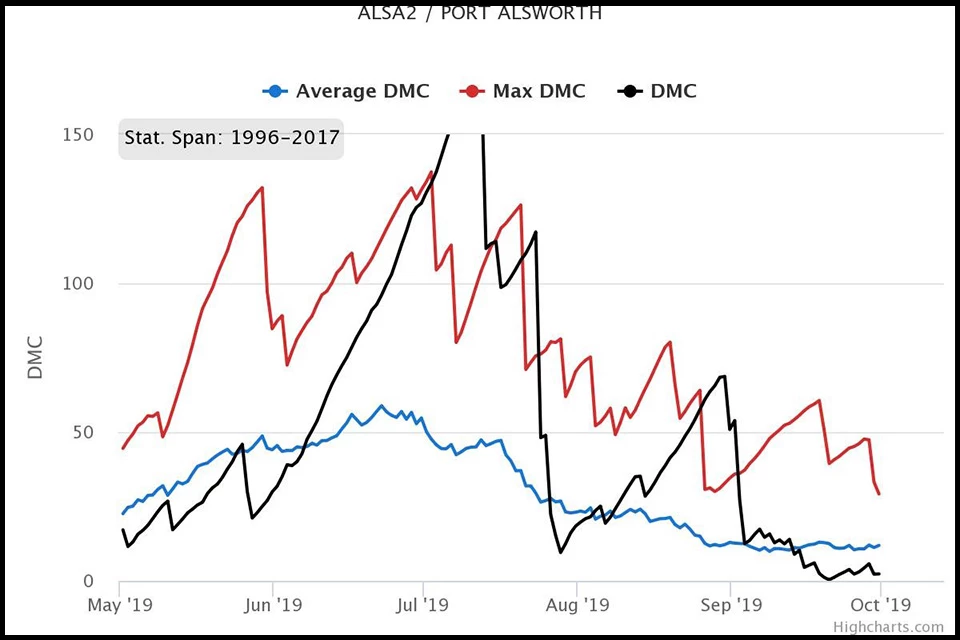

DMCs correspond to daily rainfall, temperatures and humidity. June and July were hot and dry. By June 28, Stoney RAWS began setting new daily records for recorded DMCs and by July 3, began setting new records for the highest DMCs ever recorded at Stoney RAWS. Meanwhile in Port Alsworth, the RAWS began setting new daily records for recorded DMCs on July 3 and by July 4, began setting new records for the highest DMCs ever recorded at this location.

The hot and dry weather persisted and on July 8, a new fire was discovered southwest of LACL called the Pete Andrews Creek Fire, near Iliamna Lake. While Mat-Su/Southwest Area Forestry attempted to suppress this fire, the extreme fire danger coupled with the competition for fire suppression resources across the state, the containment efforts were ineffective (low probability of success) and the fire was placed into a monitor status. The smoke from this fire was visible and impacted LACL.

Left image

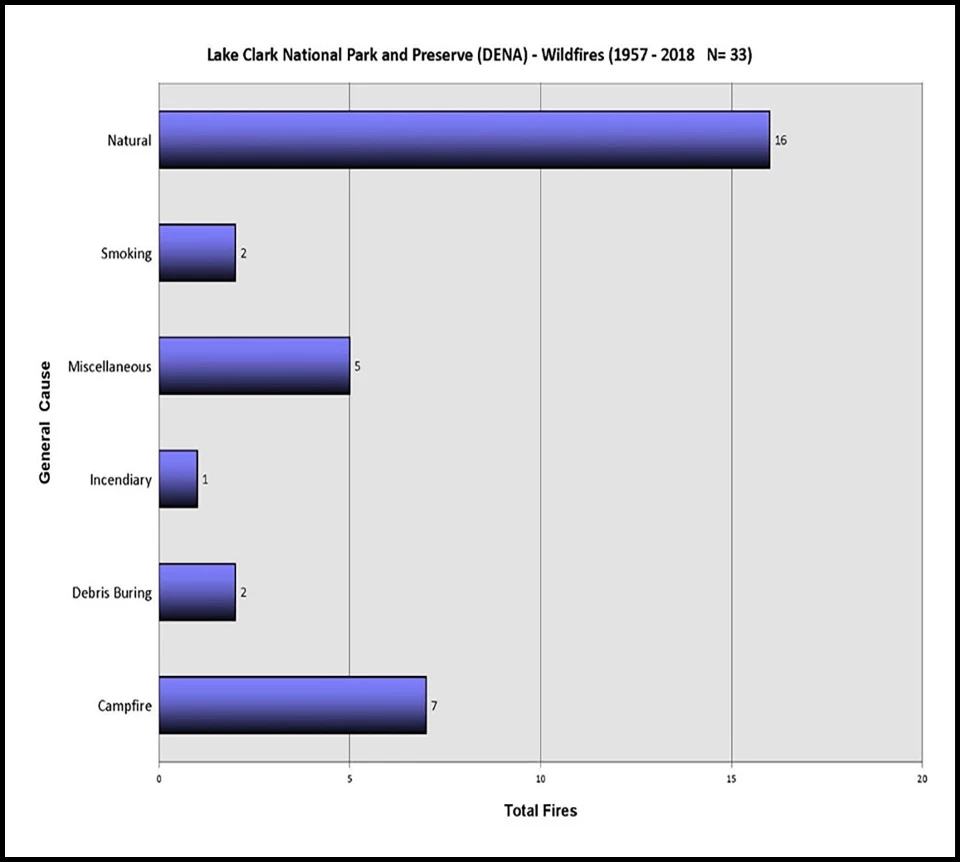

The number one cause for wildfires in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve are natural, lightning-caused fires followed by campfires.

Right image

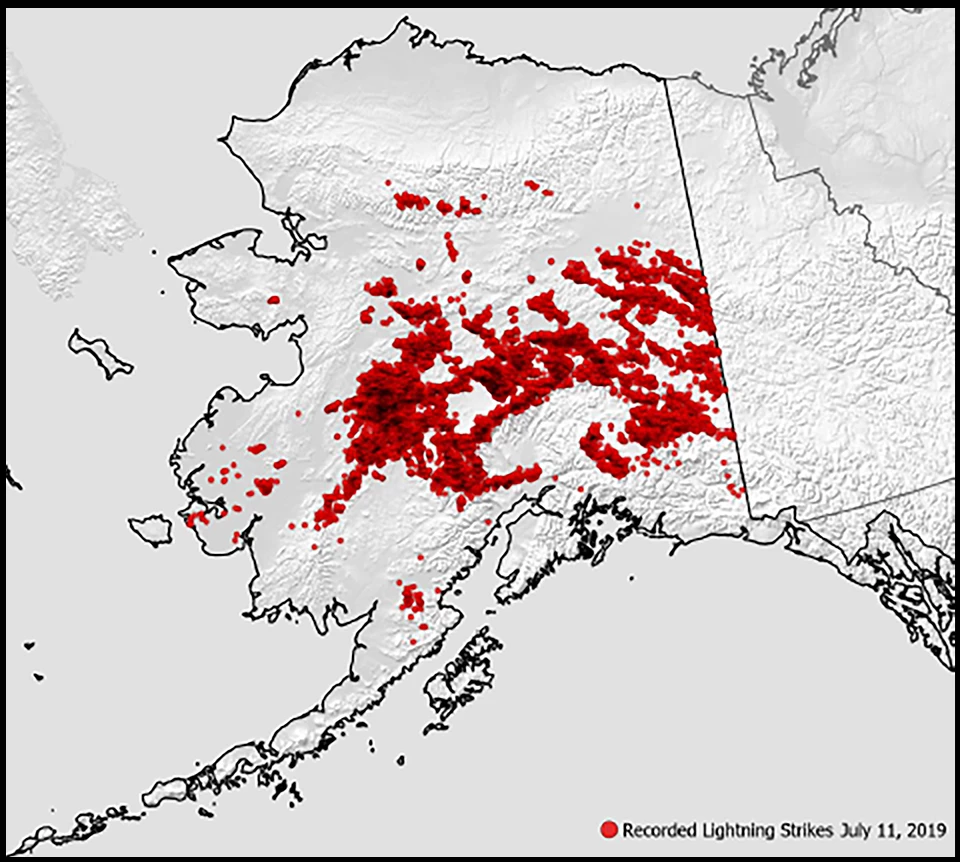

The red dots depict recorded lightning strikes on July 11, 2019.

Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy/R. Thorman

Read more!

Southwest Area FiresToward the end of July, there was some relief in the weather. The weather event that significantly reduced wildfire potential growth was widespread across southern and southwest Alaska. The Stoney RAWS finally stopped breaking daily high records of DMCs on July 24 resulting in 26 days of daily record highs. The all-time high records ceased after 10 days. Port Alsworth RAWS ceased breaking daily high records of DMCs on July 14, resulting in 12 days of daily record highs. The all-time high records came to a stop after nine days.

Left image

Port Alsworth Duff Moisture Code Data

Right image

Stoney Duff Moisture Code Data

Starting August 6, the weather started a slow, warm, and drying trend and once again, fire managers observed new daily DMC records. In the afternoon of September 1, wind speeds reach 41mph with gusts up to 54mph at the Snipe Lake RAWS. This resulted in Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) IBand heat detections in the interior of the Snipe Lake Fire. The fire did not grow during this wind event and was finally declared out on September 26 at 326.9 acres.

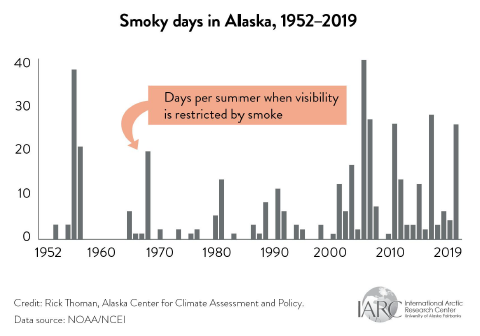

It is important to remember that with the increasing trend in fire activity, the warmer than average predicted winter for this year, and the extreme fire weather indices of last season (there are still a lot of deep, dry duff areas out there), we ask you to remain vigilant in preventing unwanted wildfires.

How to report a wildfire in your park and preserve (Internal site) (External site) and the Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System provides additional resources and information on the topics above.