Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

Gardening in Skagway

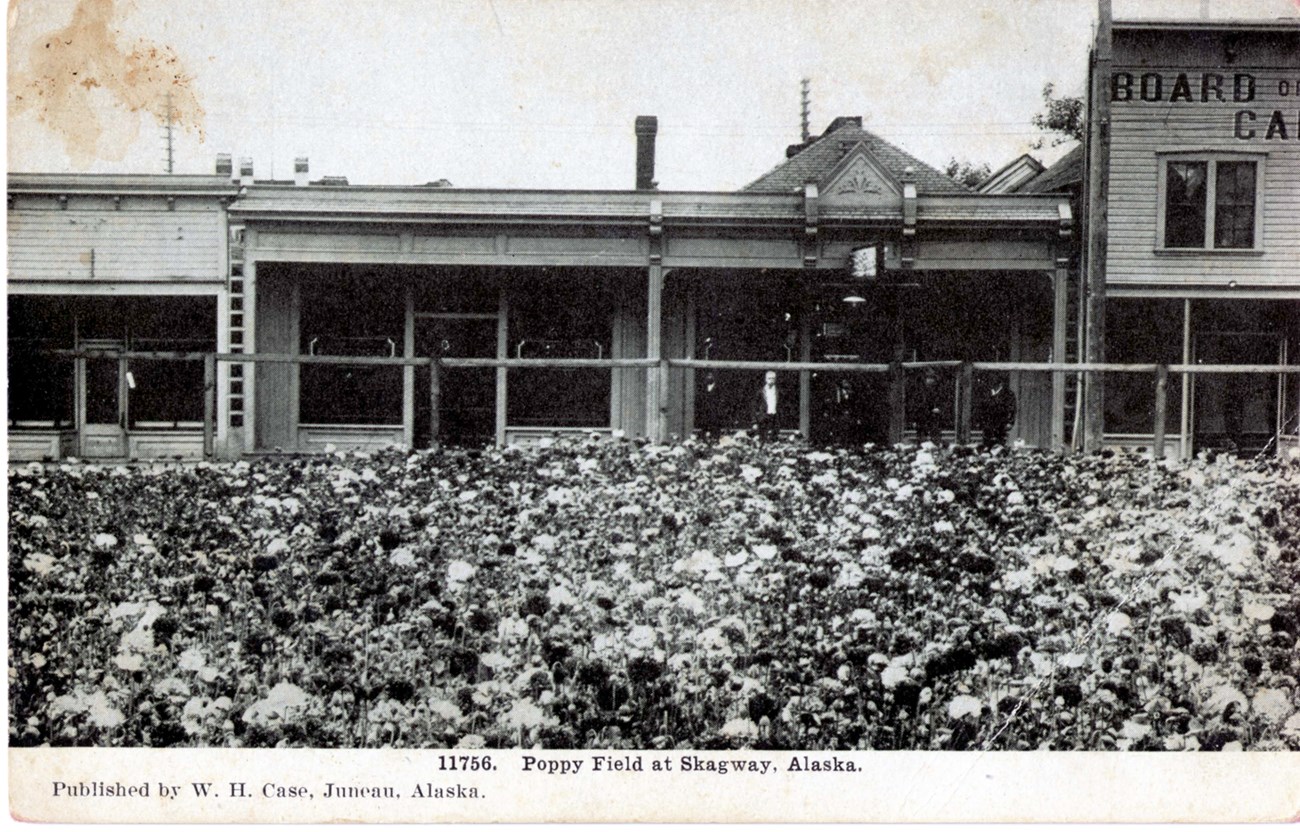

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Lois Butt Collection, KLGO 0004.015.0003_14

Eventually, markets were large enough to feasibly look at a goal of Skagway self-sufficiency. In 1901, farmers confidently stated that this goal was in sight and added onions, beets, pumpkins, and strawberries to their door-to-door deliveries. Small, individual family gardens were also successful to the point where it was said that, “the novelty of home produce has ceased."

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Shoemaker Collection, KLGO 38022

At this time flower gardens also took root in Skagway and many novice gardeners began to dabble in home adornment. The Alaskan agricultural experiment station agent serving in Sitka in 1901 visited Skagway that year and was surprised to find that the quality of flower beds was on par with the best he had seen anywhere.

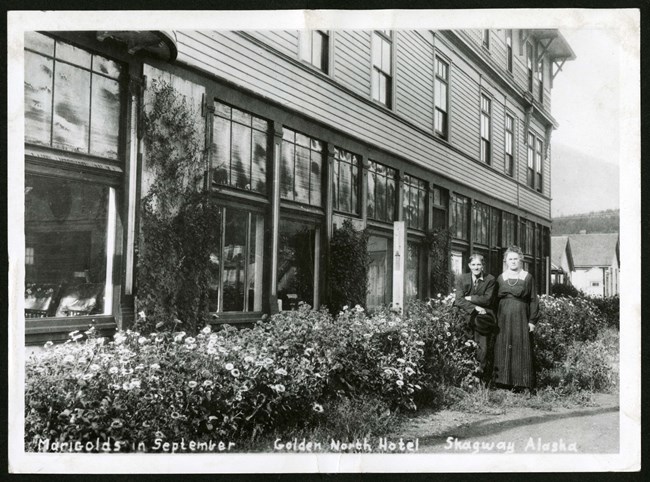

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59783d_Golden North Marigolds. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

1906 brought a new era to the White Pass and Yukon Route Railroad. Previously, the focus of the train system was on transporting miners and their supplies into the Yukon Territory. Recognizing the financial gains of catering to tourists, the company began producing material that advertised the scenic beauty and abundant wildlife all to be seen from the comfort of a train car. Among the images of the wilderness were photos of Skagway’s flower gardens, used to illustrate civility in the midst of Alaskan gold rush history. Visitors could experience both the wild frontier and the comfortable aspects of settled life in an established town before heading up the pass into a world of seemingly untouched forests and mountains. At this point, tourism played a minor role in the Skagway economy and gardens were grown by residents for their own aesthetic pleasure and sense of settlement in a town that would be largely characterized by its historical assets.

Tourism took hold in Alaska right before the United States became involved in World War I. Larger incomes across the country allowed for more travel and conflict in Europe encouraged travelers to explore new territories. Alaska became a feasible and desired destination. In response to this new interest, Skagway’s dentist and newspaper editor Dr. L.S. Keller in 1916 coined the nickname “Garden City of Alaska” to increase tourist appeal. This slogan beat out other considerations such as “the Key City”, “the Lynn Canal City”, “Gateway to the Golden Interior”, “The Garden Spot”, and “Summer Resort of Alaska”.

NPS photo/A. Lattka

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55736_Blanchard Garden. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

While flowers painted Skagway for tourists and residents alike, vegetable gardens were also thriving during this time period. Henry Clark was known as the rhubarb king and also had acres dedicated to cabbages. A weekly truck or cart carried produce grown by Clark and two other men, Walter Wills and Dale Cowen, around to residents who froze or canned vegetables for the winter.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library SP-276-8933

North of the Skagway City School ball fields lay handfuls of raised beds, access to gardening tools and a large compost pile, which make up the community garden. Fliers around town advertise flower sales and local businesses dedicated to supporting the growth of healthy residential gardens. The National Park Service adorns Broadway with a native plant garden designed and cultivated by local children. On Facebook Skagway Organic Gardening Society has 233 members as of July 2017, and is an online medium for discussion and resources for all things gardening. The residents of Skagway keep up their gardens to continue making Skagway the Garden City of Alaska.

NPS photo/K. Howard

About This Article

This article was researched and written by Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in April 2012. It was originally given as a radio talk.