Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

The People Back Home and the Sinking of the Clara Nevada

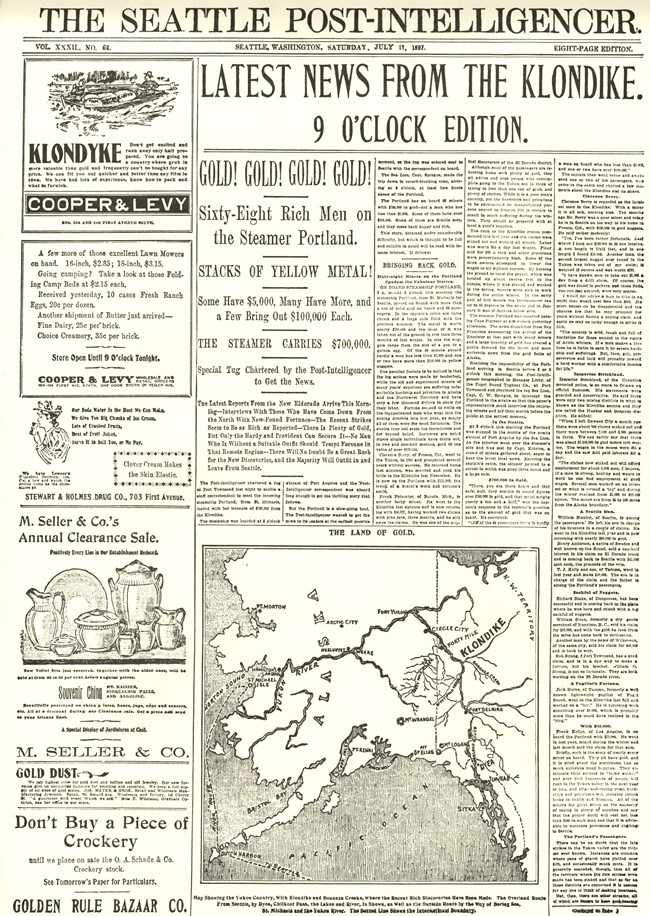

Seattle Post Intelligencer Klondike Edition, July 17, 1897

Gold! Gold! Gold!

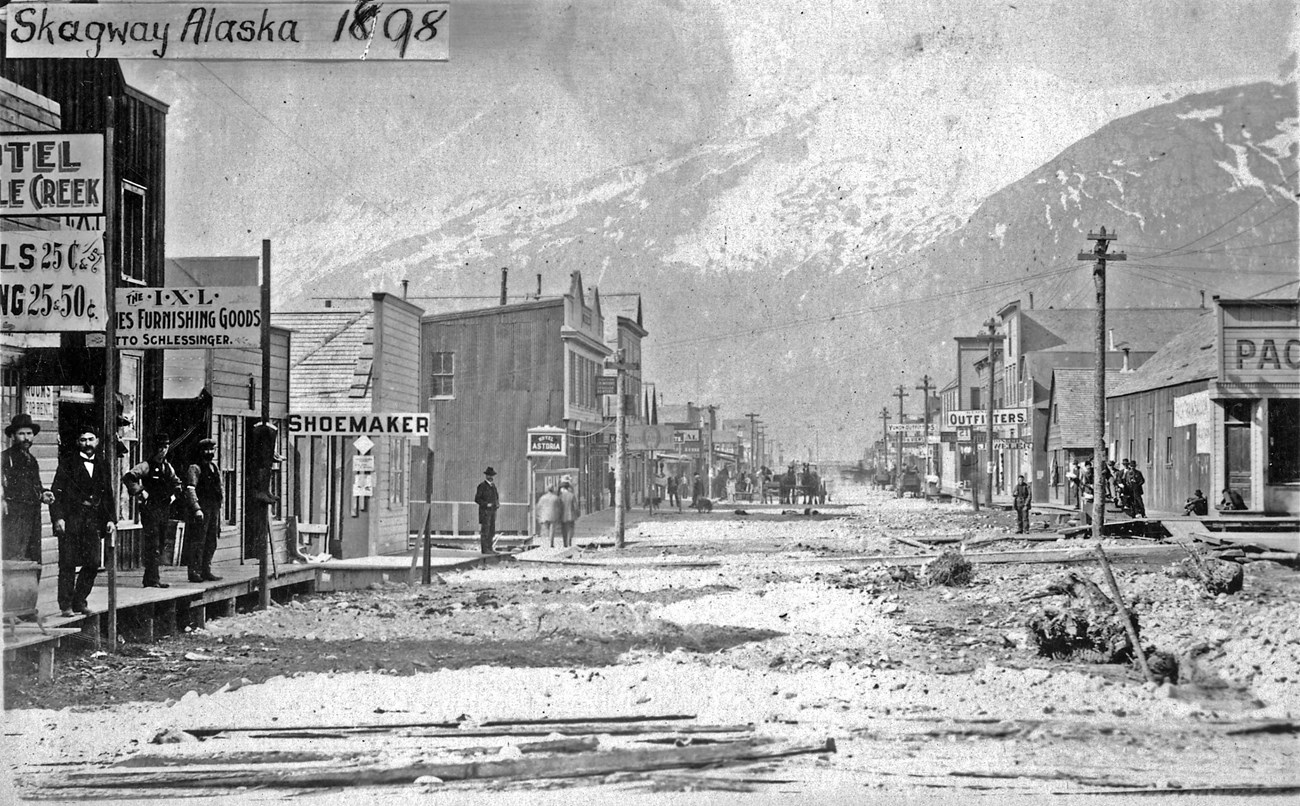

News of gold in the Klondike drew thousands of people north. Some came seeking their fortune in gold, some were entrepreneurs looking for business opportunities, and others came trying to find work. Robert Bruce Banks, a father of six, was one example of someone who came to Skagway looking for employment instead of gold. Banks left his home and family in Thorp, Washington in January of 1898, and in his first letter home to his wife Josie from Seattle, he noted that:

“an able bodied man can surely make 6 to 15 dollars per day up at Dyea or Skagway. Other people say there are too many there now. I mean to know for myself. The rush has begun and I believe I can do well to go up.”

Keep in mind that $6.00 in 1898 was roughly equivalent to $170.00 in 2016. To a father of six, who had taught school, farmed land and worked as a carpenter to support his family, the prospect of making between $6.00 and $15.00 per day was life changing, and this promise of a better life sent him to Skagway.

A Family Left Behind

The decision to leave was not easy, Josie, Bruce’s wife, wrote that their son Clyde, age 3 “insists on carrying out his threat to you, says he will get a cannon that will shoot to Seattle,” she added, “but I guess it would hardly hit you away up there. He thinks to scare you into submission so you will come back.” She also noted that the youngest member of the family, Lyman, aged 21 months, “feels all over my face every morning and then says Where’s papoo?” Harold, age 6, included one sentence, “We are reading about (…) Susy and her chickens in my reader now.” Lillian, age 9, noted that she and her brother Waldo were called upon to sing “The Moon Song” at community gathering, she added that “they want me to speak a piece [probably a memorized poem] but I don’t think I will.” Each of the older children mentioned a basket social that would raise money to pay freight charges for a new organ that was coming to the school, and had some questions about the trip north. Waldo asked, “Did you take any popcorn with you or not? Mamma said she dident [sic] think you did.” Josie had her hands full with six children and a farm, in addition to family duties, she taught choir at the school, and would probably play the organ that was being shipped to the school. Josie probably also taught private lessons, in mid-January her son Waldo wrote that a neighbor “brought us a sack of apples to pay for Addah’s singing lessons.” Josie worked hard, and left some responsibilities to her eldest children. Farm duties in particular fell to the eldest son, Waldo, age 13.

Life On The Home Front

Josie reassuringly wrote in her first letter that Waldo, “tends to his chores” and added that neighbors were helpful, writing “folks here are very kind” and “we are not left much alone except during the day while the children are in school.” But having her husband gone was a challenge, Josie’s first letter ended with “The children are all writing too and I must stop now and go to work.” Indeed, a couple of weeks later Waldo opened with “we are all right now the cow is getting along all right too.” A sick cow the week before had probably been Waldo’s responsibility. Waldo also milked the cow at night, on one occasion he talked about seeing an owl that “winks and blinks at the light” from the barn. Another evening his chores did not go as smoothly. When Waldo “went out to milk the cow” he found “some chickens in the feed box” so he “put the lantern on the wheat box and when [Waldo] pulled the old ro[o]ster out he tipped the lantern…and the burner dropped out and started blase [sic],” luckily Waldo “put it out so it did not hurt any thing [sic].” Waldo was learning to solve problems and take extra responsibility in his father’s absence. Daisy, the eldest daughter, age 15, was also introduced to the realities of the world. A couple of weeks after Bruce left, she wrote, “Mr. Peck acts kind of queer about paying that three dollars in vegetables. The other day, Mamma asked him about cabbage and he said it was all buried up and then she asked about potatoes and he answered the same.” In the community, food and bartering seemed to be a common form of payment. This food and Josie’s income from singing lessons kept the family afloat.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55887. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

No Work To Be Found

While Josie and her children shouldered extra responsibilities, Bruce cared deeply for his family, and was aware of his wife’s situation. In a letter on January 31, 1898, he wrote, “I can hardly sleep at night for thinking, ‘Are you all well? I have not had a word from you since the letter I got in Seattle. Don’t let Clyde go to sleep with cold feet. Daisy, Don’t [sic] let Mama over work [even] if you have to stay out of school.” Bruce had the additional disadvantage of unreliable mail service, and never received any of the letters that his family sent from Washington. He rapidly became lonely and discouraged when he found that employment opportunities in Skagway were limited. On January 31, 1898, just 10 days after he arrived in Skagway, Bruce wrote,

"Do keep well and try to not worry about me. [He wrote] The buildings here are generally cheap and not much contracting done. Most all is day work. I am told some are offering to work for 30 cents an hour but that won’t do for me and won’t hold me here. The symptoms are that all lines of work will be overdone. Most all the people coming in now are coming to work. I cannot say how it will be for packing. Don’t fail to write me as many as can from baby up. You know I shall be very lonesome and a letter will help me."

Steady employment that paid over cents an hour never materialized for Bruce Banks, on January 29th he wrote, “you can see notices up on some buildings where there has been some packing let. ‘No packers wanted.’ On the road office a notice says ‘No men wanted.’ I have worked most of the time since coming here a day here and there, but hundreds are hunting work.”

Turning To Home

It did not take long for Bruce to make the decision to return to Washington, on February 2nd he wrote that he had been working and was “very healthy,” “but pay here is generally uncertain.” Bruce added that he “did not come here for health or poverty. Had plenty of that before,” so he wrote that he planned to leave on the Alki, a steamer that regularly arrived in Skagway. However, for an unknown reason, Bruce decided to take the Clara Nevada, a steamer that ran aground on Eldred Rock on Saturday, February 5, 1898. There were no survivors, Bruce Banks never made it back to his family.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 60185. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

An Uncertain Fate

Because the family assumed that Bruce was on the Alki, they dutifully wrote more letters. Waldo in particular was looking forward to his father’s return, in a February 13th letter he urged, “If you can come home soon, come, for I don’t think I will get the crop in right.” Sadly, Waldo would have to sow the spring crop on his own. As weeks passed, letters became increasingly frantic, on March 9, 1898 Josie wrote, “We are very anxious about you in view of the sickness and the Clara Nevada disaster about the time you said you might return on the Alki…O I pray that if you are alive you may come home as soon as possible only do not any risk on a boat of uncertain reliability. The wheat will be put in next week all right,” she assured, but closed with “We are well as our anxiety will permit.” A postscript read “We can send you money if you want it.” Daisy, the oldest was equally anxious about her father and her mother. “We want you to come home as soon as you can,” she wrote on March 6, “no matter about what wages you may be getting there…It is fine spring weather here, some buttercups in blossom. You could get work here all right. All usually well, tho Mamma has a headache a good deal.”

The family closely followed the route of the Alki in the newspapers, but when their father never came home, it became clear that Bruce had taken the Clara Nevada. On April 8, Mrs. Baker a friend in Skagway wrote, “I have received your letter of March 9th today but know that by this time you must know of what we consider Mr. Bank’s untimely end. I hunted up all of the facts as near as I could and sent them to your Uncle sometime ago, just as soon after the disaster as I could. We feel sure that he met his death on that boat because he left our house expecting to go on her, and that is the last we have heard from him.”

The tragic story of Bruce Banks highlights the family connections that many Klondike accounts overlook. It is true that the majority of stampeders were white, male and single, but they had brothers, sisters, mothers and fathers who cared for them and worried about their well being. Relatives at home could follow reports of the Klondike through newspapers and letters. This news was a valuable link to family members who were far away on a cold frontier.

About this article

This article was researched and written by Susannah Dowds, the Assistant Historian at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in June 2016. It was originally given as a radio talk. Information was supplied by the following sources:

Rodney Edvinsson, “Portal for Historical Statistics,” Stockholm University, accessed 7 February 2017. http://www.historicalstatistics.org/

Pam Randels and Blythe Carter. “Shipwrecks of the Lynn Canal and Juneau Area,” Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center, updated 2013. http://www.sheldonmuseum.org/Vignettes/shipwrecks.htm