Last updated: June 11, 2019

Article

The Ceramics Assemblage from the Kingsley Plantation Slave Quarters

For the past four years, a University of Florida field team has conducted archaeological excavations at Kingsley Plantation, located in the National Park Service’s Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, in Duval County, Florida. Kingsley Plantation was active in the early nineteenth-century and the excavations have focused primarily on the slave quarters from this period in an attempt to reconstruct the daily lives of their inhabitants. The following report describes the ceramics assemblage recovered from the Kingsley Plantation Slave Quarters, in an initial effort towards the project’s broader interpretive goal. After a description of the ceramics assemblage, the collection is compared to the archetypal antebellum plantation of Cannon’s Point Plantation, GA. Such a basic analysis of the artifacts is a fundamental first step to interpreting the role of material objects in the slaves’ daily lives.

Settlement of Fort George Island

The English, Spanish, and American governments struggled for decades during the 18th century over the control of Florida’s rich resources. Fort George Island changed hands several times, from Spanish control to British and back to Spanish; eventually, it became American territory. The first change of hands from Spanish to British control in 1763 “ushered in the era of Plantation Agriculture” (Stowell 1996).

European farmers began to occupy the island in the 1760s, and a large plantation was established by John McQueen, a planter from South Carolina in 1798. McQueen built the infrastructure of his plantation on the north end of the island, clearing land to be used by the next several owners of Fort George (Stowell 1996).

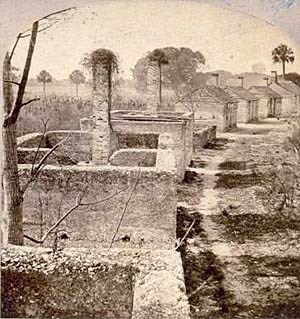

In 1811, “rural residents of East Florida” banded together to wrest control of the colony away from Spain for the United States (Stowell 1996). This uprising, termed the Patriot Rebellion, was unsuccessful. Fort George Island was sold to Zephaniah Kingsley (Stowell 1996). Kingsley was a wealthy shipbuilder and slave trader who had lost his previous plantation on the St Johns River, Laurel Grove, to Seminole raiders during the Rebellion. He moved his family and remaining slaves to the more defensible location of Fort George in 1814, where they remained for the next two decades (Schafer 2003). The entire plantation infrastructure (except the main house) had been destroyed by Seminole raiders during the rebellion. When the Kingsleys arrived, they quickly constructed buildings on the property, including an arc of 32 shell sand-and-shell-mortar, or tabby, cabins that housed more than 200 slaves (Walker 1988).

Zephaniah Kingsley and his wife, Anna, are perhaps the most well-known and widely discussed figures that ever inhabited Fort George Island (Schafer 2003). Kingsley wrote a great deal, and published several pamphlets and letters about his philosophy of slavery. His ideas were revolutionary for the time, espousing ideals of racial interdependence, the superiority of the “African” physique, and benevolent treatment of slaves (Stowell 2000). His affection for his wife, Anna, one of his former slaves, is often brought to bear as a demonstration of Kingsley’s affinity for “Africans.”

Anna’s life is well documented as an exceptional case of a slave-turned-owner, free black woman in America (Stowell 1996). The Kingsleys treated their slaves in a much more humane and laissez-faire manner than was common at the time. After the day’s assigned tasks were finished, the slaves of Kingsley Plantation were allowed to spend their time as they pleased, growing food in their own gardens, hunting, fishing, socializing, etc. The formation of stable family units was encouraged and Kingsley allowed the enslaved to continue their own native religious practices (Schafer 2003).

The United States took possession of Florida in 1821, and the tolerant slave system of the Spanish was replaced by the harsh American slave economy. Kingsley fought legislation in Florida that would increase racial tensions, but he was unsuccessful each time and the barriers between enslaved and slave owner became further and further cemented (Stowell 2000). Seeing the way that East Florida was headed, Kingsley decided it was time to move his family to Haiti, a colony that was touted as a safe home for free blacks. Anna and her youngest child left Fort George Island in 1837. Two years later, Kingsley sold his plantation and forty of his slaves to two of his nephews. Beginning in the 1860s, the Island passed from owner to owner every few months or years until the Civil War.

A wave of tourist development followed Fort George's agricultural era. Several luxury hotels were constructed on the island, all of which were successful until each accidentally burned down in the 1930’s. The island remained a winter retreat for families that could afford private homes, but tourism and vacationing did not revive again until the 1920s. In 1923, Rear Admiral Victor Blue founded the Army and Navy Club on Fort George and rejuvenated tourism for the wealthy. The Club encompassed the area of the island that had been the home of so many planting families, the part now known as Kingsley Plantation. In the wake of the Great Depression and World War II, the Fort George Club closed its doors and the island was left alone for decades (Stowell 1996).

Through a series of land and property sales, the portion of Fort George Island that had been the site of so much activity in the past century and a half came into the possession of the state of Florida in the 1980s. Much of Fort George Island is now a national park, part of Timucuan Ecological and Historic National Preserve.

Excavation of Kingsley Plantation

Through four seasons of field schools, archaeologists have recovered much information about the conditions of daily life and retention of African ideology and practices amongst enslaved persons on Fort George Island during Zephaniah Kingsley’s occupation. Three cabins were chosen for excavation (West-12, West-13, and West-15). Archival records indicate that cabins without standing walls were robbed of their tabby by the early 1870s to be used as a rubble foundation for a boathouse adjacent to the main house. This information establishes a terminal date for occupation of the cabins.

Ceramics Analysis

The ceramic assemblage used for this analysis consists only of ceramics from occupations from the Antebellum Period of Fort George Island. Prehistoric ceramics were recovered from almost every unit excavated, but it is not likely that the vessels these sherds represent were actually used in the historical periods of the island’s history. Many of the recovered sherds exhibit evidence of having been embedded in the tabby that made up the cabins’ walls. Other prehistoric sherds were recovered far below the remains of the cabin floors, again indicating that the associated vessels were not part of the cabin or post-cabin contexts.

As an assemblage, the ceramics from the Kingsley Plantation Slave Quarters are fairly typical of a nineteenth century, low economic status site. The portion of the assemblage that can be identified contains a very high number of tablewares (plates, platters, bowls, and teawares). This is not unusual, as ceramics were mostly relegated to a serving capacity by this point in history. By the time the cabins were being occupied, most cooking was performed in metal (iron) vessels over an open fire or a in a cast iron oven.

The 887 cabin-era sherds recovered from the 2006-2008 excavations were analyzed as individual artifacts, identified, weighed, catalogued, and labeled (see Table 1). They were then sorted into vessel lots based upon form, and decorative technique, style and motif. Provenience of the individual artifacts was not included in the sorting criteria. The sherds were sorted into groups representing 68 vessels (Table 2).

The vast majority of the ceramics recovered from the Kingsley slave quarters were classified as pearlware, a cream-colored refined earthenware of English Manufacture and popular as tableware during the years of 1780-1820 (Miller 1991). Pearlware was easy to mass produce, making them relatively affordable across class lines. Vessels made near the beginning of the pearlware date range were usually hand-painted in blue geometric or floral patterns. With the advent of transfer-printing, more intricate designs were developed including landscapes, detailed floral arrangements, and domestic scenes. The choice of vessel decoration appears to have been based primarily on personal taste; no connections have yet been made between preferred motif and class status. The rest of the assemblage contains lead-glazed redwares and stonewares, few creamwares (an earlier version of pearlwares), and one porcelain fragment.

NPS

Using Ceramics to Date Occupation

When the ceramic assemblage is used to calculate an approximate date of occupation of the slave cabins, the results of those computations can be compared to the dates provided by the historic records, revealing information about the residents’ purchasing power. A date of occupation of the cabins built for slaves was computed using the mean ceramic dating (MCD) formula developed by South (1972, modified in 1974). The formula provisionally dates sites for which no historical documentation is available to determine chronological context. Archeologists working on historical period sites with European ceramic wares commonly calculate the MCD of an assemblage using this formula based on median dates of ceramics present at the site (Hume 1969; Miller 1991).

The mean ceramic date formula works best when used with diagnostic ceramics with a period of manufacture of less than 100 years (Miller 1991). Two types of ceramics were not included in the calculations of the mean ceramic date for the slave quarters assemblage from Kingsley Plantation. Lead-glazed redwares and stonewares have been manufactured for centuries and are, in fact, still made today. For this reason, these categories were eliminated from the MCD calculations.

A total of 63 vessels were used in the mean ceramic dating formula. The MCD that resulted from these calculations was the year 1809, five years before the known construction of the tabby cabins, based on historical documentation. The early date may reflect the economic circumstances of the cabins’ occupants. As slaves, they would not have had the expendable income to continually purchase new ceramics for personal use. Therefore, it is likely that the slaves used what ceramics they possessed for long periods of time simply because they did not have the funds or opportunities to purchase more. Another possible explanation for the early date resulting from the mean ceramic dating formula could be that the ceramics assemblage reflects the extended use life of those older, more worn, or outdated vessels handed down from the plantation owner, Zephaniah Kingsley. Unfortunately, such a hypothesis could only be definitively tested through a comparison with a ceramics assemblage from the plantation’s main house, which is not available at this time.

NPS

Using Ceramics to Examine Socio-Economic Status

The “CC Index” is a way to gauge the cost of an entire ceramics assemblage by calculating the cost of the individual refined earthenwares that it includes, based on index values (Miller 1991). The index values were computed from exhaustive studies of price lists for refined earthenwares from the late 18th century through the late 19th century (Miller 1980). Before computing the CC Index of an assemblage, an archaeologist must sort vessels by form, size, and decorative technique. Then, the index value for each vessel type is multiplied by the number of vessels of that type. The results for each vessel type are then summed and divided by the total number of vessels. This results in the average CC Index value for the assemblage. This process is performed three times for each assemblage; once each for plates, cups, and bowls.

The average CC Index values of a site can be used as a basis for the comparison of different sites. As the CC Index reflects the cost of the ceramic wares, some archeologists have used it as a marker of economic class or social status when comparing sites. For instance, Adams and Boling (1989) compared the CC Index values of 44 archeological sites from plantations across Georgia. They used the values to argue that, for selected vessel forms, slaves might have had more expensive vessels than their masters, and that the slaves’ had much more expensive ceramics than white farmers and businessmen in the contemporary North (Adams and Boling 1989).

Of the 68 ceramic vessels, only 26 were useful for to determining average CC Index values (see Table 3). There were 18 identifiable plates; all blue or green painted shell-edged with an index value of 1.33. Therefore, the average CC Index for plates at the Kingsley Plantation slave quarters was 1.33. There were 3 identifiable cups; all blue transfer-printed London size teacups with the index value of 3.67. Therefore, the average CC Index for cups at the Kingsley Plantation slave quarters was 3.67. There were 5 identifiable bowls, in three different decorative styles: two annular slipped with index values of 1.2, two blue hand-painted with index values of 1.6, and one polychrome hand-painted with an index value of 1.6. Therefore, the average CC Index value for bowls at the Kingsley Plantation slave quarters was 1.44. The average value for cups was nearly three times the average for either plates or cups. The most common expenditure pattern in archeological assemblages from historic sites in North America exhibits the highest average index value for teacups and the lowest average index value is for bowls (Miller 1991). The assemblage from Kingsley Plantation seems to fit this established pattern.

Comparison to Cannon’s Point

Comparison of the Kingsley Plantation slave quarters ceramics with other ceramic assemblages of similar age provides a better appreciation of the individual character of the former assemblage. One of the most applicable comparisons available is that of Cannon’s Point, also known historically as Couper Plantation, located on the Georgia Sea Island of St. Simon’s Island. Cannon’s Point was a cotton plantation owned by the Couper family from 1794 to the 1860s (MacFarlane 1975). Cannon’s Point consisted of a fine home for the planter and his family, a lesser dwelling for the white overseer, and two identified sets of slave cabins (MacFarlane 1975). By 1862, when Union troops occupied the island, the main house was gutted. The property was essentially unoccupied during Reconstruction, save for a few caretakers (MacFarlane 1975). In 1876, the main house was purchased and occupied until a fire destroyed it in 1890, and the plantation was finally abandoned (MacFarlane 1975).

Archeological excavations focused on one of the cabins; a single room of wood frame construction with a red brick fireplace and a compacted dirt floor; estimated to have been occupied circa 1820s to 1860s (Otto 1975). The Cannon’s Point collection also contained a great majority of pearlwares along with some creamwares, stonewares, redwares and porcelains. However, whitewares and yellowwares were also recovered; consistent with the later occupation of these cabins than those of Kingsley Plantation.

Analysis of the ceramics from the Cannon Point slave cabin identified a pattern of ceramic distribution that became a signature for status differentiation on historic archeological sites in North America (Moore 1985, Adams and Boling 1989).

Otto (1984:66) remarked that “a comparison of ceramic types from the slave, overseer and planter refuse revealed that slaves and overseers used remarkably similar ceramics”. He further noted that:

“a comparison of ceramic shapes from the plantation sites revealed that the slaves, overseers, and planter family also used rather different shapes of ceramics. In particular, there were striking differences in the tableware shapes – serving bowls, plates, and platters. Serving bowls composed 44% of the slaves’ tableware shapes, 24% of the overseers’ tableware, and only 8% of the planter’s tableware. In turn, serving flatwares (plates and platters) were most common at the planter’s site, composing over 80% of the tableware, but were less common at the overseer’s site and least common at the slave cabin (Otto 1984:66).

In other words, a high proportion of hollowware vessels to flatware vessels were interpretable as a sign of low economic classes on an archeological site. Otto’s model was the first to be accepted among researchers in the field of African-American archeology as a reliable pattern for the identification of a signature of enslaved presence at a site. Moore (1985), Brown (1994), and Russell (1997), among others, have applied this model across the southeast United States and found it fairly accurate.

This observed pattern of slaves owning a relatively high proportion of hollowware vessels has become the norm for identifying enslaved workers in the archeological record. The question to answer in this study is whether the assemblage from the Kingsley Plantation slave quarters fits this expected pattern.

A comparison of the percentages of types present in the ceramics assemblages from the occupation of the Kingsley Plantation slave quarters and the Cannon’s Point North Third Slave Cabin is summarized in Table 1. There are notable similarities and differences between the two assemblages in terms of ceramic types. Pearlware (85.3% at Kingsley Plantation and 84.0% at Cannon’s Point) is the most common type identified. However, the relative amounts of porcelains, creamwares, and whitewares at the two sites differ significantly.

Differences in frequency of creamwares and whitewares are most likely explicable by reference to the years in which the sites were occupied. The Kingsley Plantation site was occupied a few years earlier in time than the Cannon’s Point site and the ceramics assemblages reflect this difference. Creamwares (manufactured from circa 1760 to circa 1820), for example, are present at Kingsley Plantation, but not at Cannon’s Point. Conversely, whitewares (manufactured from circa 1805 to the present, but not recovered from American sites until after 1820) were recovered from the Cannon’s Point occupation but not that of Kingsley Plantation, reflecting the later years of occupation on former site.

The ratio of identifiable hollowware vessels to flatware vessels present in the Cannon’s Point North Third Cabin is approximately 1:1 (1.1875:1 to be exact). This is what Otto has set as a “high” amount of hollow wares in an assemblage. The Kingsley Plantation Slave Quarters assemblage reveals a much higher ratio of identifiable hollowware vessels to flatware vessels (1.7774:1).

So, does the Kingsley Plantation ceramics assemblage fit into the established slave status pattern identified by Otto and exemplified by the Cannon’s Point assemblage? The answer is both a resounding “Yes!” and a hesitant “No.” The Kingsley collection does indeed show a very high proportion of hollowware vessels present in the assemblage, thus confirming the pattern. However, the proportion is nearly twice that of Cannon’s Point. Is this difference meaningful? Does this indicate that the enslaved at Kingsley chose to use more bowls than plates, or is it merely an anomaly resulting from methodological biases? These are research questions to be answered in the future.

Conclusions

The meaning of the differences between collections from the Kingsley quarters and Cannon’s Point is unclear. However the analysis demonstrates the Kingsley collection’s resemblance to the archetypal Cannon’s Point status pattern. The full implication of ceramics as a class of artifacts in the field of African American Archaeology is beyond the scope of this paper. However, this study of the slave quarters’ ceramics will enable further exploration of enslaved foodways and help forge connections to theories about retaining or recreating African or creolized identities. Future studies will also address the implications of slaves choosing one type of ceramic vessel over another.

By Karen E. McIlvoy, University of Florida

References

Anonymous

2004 Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, Kingsley Plantation Cultural Landscape Report. Prepared by Hartrampe. Submitted to Historical Architecture, Cultural Resources Division, Southeast Regional Office, National Park Service. n.p.

Adams, William Hampton and Sarah Jane Boling

1989 Status and Ceramics for Planters and Slaves on Three Georgia Coastal Plantations. Historical Archaeology 23(1): 69-96.

Brown, Kenneth L.

1994 Material Culture and Community Structure: The Slave And Tenant Community At Levi Jordan’s Plantation, 1848-1892. In Working Toward Freedom: Slave Society and Domestic Economy in the American South, ed. by Larry E. Hudson, Jr., pp. 95-118.

Fairbanks, Charles H.

1974 The Kingsley Slave Cabins in Duval County, Florida, 1968. Conference on Historic Sites Archaeology Papers 7:62-93.

Davidson, James M.

2007 University of Florida Historical Archaeological Field School, 2007 Preliminary Report of Investigations, Kingsley Plantation (8Du108), Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, National Park Service, Duval County, Florida. Submitted to the United States Department of the Interior, National Parks Service, Southeast Archaeological Center, Tallahassee, Florida.

Lewis, Lynne G.

1985 The Planter Class: The Archaeological Record at Drayton Hall. In The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life, edited by Theresa Singleton, pp. 121-140. Academic Press, Orlando, FL.

MacFarlane, Suzanne

1975 The Ethnoarchaeology of a Slave Community: The Couper Plantation Site. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida.

Miller, George

1980 Classification and Economic Scaling of 19th Century Ceramics. Historical Archaeology 14:1-40.

1991 A Revised Set of CC Index Values for Classification and Economic Scaling of English Ceramics from 1787 to 1880. Historical Archaeology 23(1):1-25.

2000 Telling Time for Archaeologists. Northeast Historical Archaeology 29: 1-21.

Moore, Sue Mullins

1985 Social and Economic Status on the Coastal Plantation: An Archaeological Perspective. In The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life, ed. by Theresa A. Singleton, pp.141-160. Orlando: Academic Press.

Noel Hume, Ivor

1969 A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Otto, John Solomon

1975 Status Differences and the Archaeological Record -- A Comparison of Planter, Overseer, and Slave Sites from Cannon’s Point Plantation (1794-1861), St. Simons Island, Georgia. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Florida, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

1984 Cannon’s Point Plantation 1794-1860: Living Conditions and Status Patterns in the Old South. Orlando: Academic Press.

Russell, Aaron E.

1997 Material Culture and African-American Spirituality at the Hermitage. Historical Archaeology 31(2): 63-80.

Schafer, Daniel L.

2000 Zephaniah Kingsley’s Laurel Grove Plantation, 1803-1813. In Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida, edited by Jane G. Landers, pp. 98-120. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

2003 Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley: African Princess, Florida Slave, Plantation Slaveowner. University Press of Florida.

South, Stanley

1972 Evolution and Horizon as Revealed in Ceramic Analysis in Historical Archaeology. The Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers, 1971 6:71-116.

1974 Palmetto Parapets: Exploratory Archaeology at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina, 38CH50. In Anthropological Studies #1, Occasional Papers of the Institute of Archeology and Anthropology. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina.

1977 Method and Theory in Historical Archaeology. New York: Academic Press.

Stowell, Daniel W.

2000 Balancing Evils Judiciously: The Proslavery Writings of Zephaniah Kingsley. University Press of Florida.

1996 Timucuan Ecological and Historical Resource Study. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Southeast Field Area, Atlanta, GA.

Walker, Karen Jo

1988 Kingsley and His Slaves: Anthropological Interpretation and Evaluation. MA Thesis. Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Type |

Kingsley Plantation |

Cannon Point |

||

|

|

Number |

Percentage of Assemblage |

Number |

Percentage of Assemblage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creamwares |

1 |

1.5 |

|

|

|

Transfer-Printed |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Plain |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Handpainted |

1 |

1.5 |

|

|

|

Stenciled |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Ironstone |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Lead-glazed Redwares |

3 |

4.4 |

2 |

1.6 |

|

Majolicas |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Pearlwares |

58 |

85.3 |

105 |

84 |

|

Slipped |

15 |

22.1 |

22 |

17.6 |

|

Transfer Printed |

12 |

17.6 |

33 |

26.4 |

|

Handpainted |

11 |

16.2 |

12 |

9.6 |

|

Plain |

2 |

2.9 |

26 |

20.8 |

|

Edged |

18 |

26.5 |

12 |

9.6 |

|

Porcelain |

1 |

1.5 |

5 |

4 |

|

Industrial |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Non-industrial |

1 |

1.5 |

5 |

4 |

|

Stoneware |

5 |

7.3 |

9 |

7.2 |

|

Salt-glazed |

3 |

4.4 |

5 |

4 |

|

Unglazed |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

Alkaline-glazed |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Lead-glazed |

2 |

2.9 |

3 |

2.4 |

|

Whitewares |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2.4 |

|

Plain |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Transfer-Printed |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

Sponged |

|

|

3 |

2.4 |

|

Yellow-wares |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

Painted |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

Unidentifiable |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

68 |

100 |

125 |

100 |

TABLE 1 – Vessels from Kingsley Plantation And Cannon Point by Type

|

Form |

Kingsley Plantation |

Cannon’s Point |

||

|

|

Number |

Percentage of Assemblage |

Number |

Percentage of Assemblage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hollowware |

32 |

47.1 |

57 |

47.5 |

|

jug |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2.5 |

|

bowl/basin |

5 |

7.4 (15.6) |

35 |

29.2 |

|

cup |

3 |

4.4 (9.3) |

13 |

10.8 |

|

bottle |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

jar |

6 |

8.8 (18.7) |

5 |

4.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flatware |

18 |

26.5 |

48 |

40 |

|

plate/platter |

18 |

26.5 |

39 |

32.5 |

|

saucer |

0 |

0 |

9 |

7.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other |

|

|

8 |

6.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

18 |

26.5 |

7 |

5.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

68 |

100.1 |

120 |

100 |

TABLE 2 – Vessels from Kingsley Plantation and Cannon’s Point by Form

|

Plates |

CC Value |

n = 18 |

1.33 |

|

shell-edged |

1.33 |

x18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Teacups (printed) |

CC Value |

n = 3 |

3.67 |

|

teacups (printed) |

3.67 |

x3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bowls |

CC Value |

n = 5 |

1.44 |

|

annular (dipt) |

1.2 |

x2 |

|

|

blue painted |

1.6 |

x2 |

|

|

poly painted |

1.6 |

x1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mean CC Index Value |

2.15 |

TABLE 3 – CC Index Calculations for Kingsley Plantation Ceramics

Tags

- timucuan ecological & historic preserve

- florida

- south

- southeast region

- archeology

- archaeology

- southeast archeological center

- timucuan ecological and historic preserve

- plantation

- plantation architecture

- slave quarters

- african american

- african american sites

- ceramics

- antebellum

- 19th century

- research

- evaluation

- analysis