Last updated: December 13, 2023

Article

Japanese American Life During Incarceration

NPS photo

The process of removal began in late March 1942, as Japanese Americans throughout the West Coast were given a week’s notice to get their affairs in order and report to temporary detention centers built on local fairgrounds and racetracks. Allowed to bring with them only what they could carry, people were forced to abandon their homes and the lives they had built over generations.

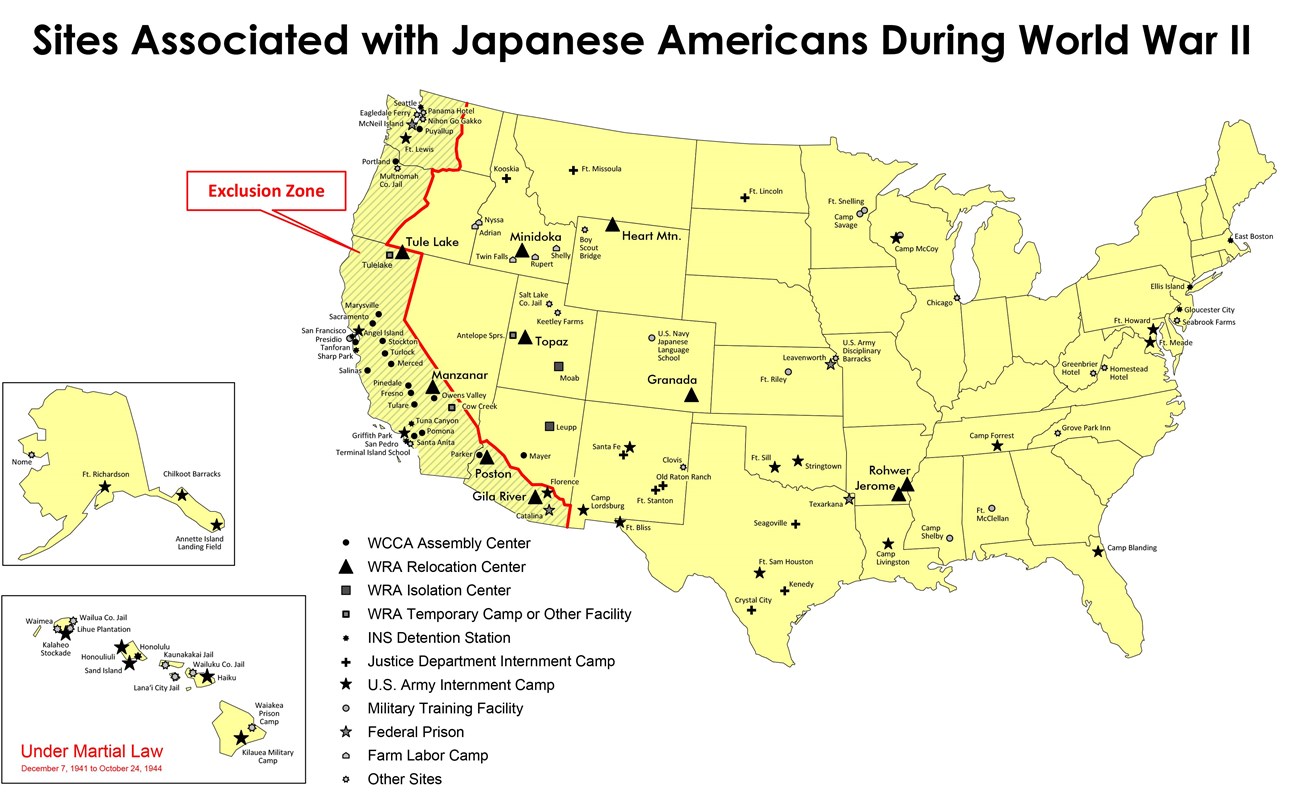

By the end of the summer, the US Army transported everyone to one of ten incarceration camps, euphemistically called “War Relocation Centers.” These camps—Amache (also known as Granada) Gila River, Heart Mountain, Jerome, Manzanar, Minidoka, Poston, Rohwer, Topaz, and Tule Lake—were hastily built and located in some of the most desolate places in the country, exacerbating the conditions of forced incarceration with the extreme weather of deserts and swamps.

Incarcerees slowly adjusted to the conditions of the camps, but the surrounding guard towers, barbed wire, and armed soldiers acted as constant reminders of their forced confinement. The last of the “War Relocation Center” camps closed in 1946, but the last camp that held Japanese Americans closed in 1948.

A 1982 congressional report called Personal Justice Denied stated that the incarceration was due to “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” This congressional study found that the exclusion and forced imprisonment of Japanese Americans by the US government was based on the false premise of military necessity. There was no documented evidence of Japanese American espionage or sabotage during the war.

Through efforts of many within and outside of the Japanese American community, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was formalized. President Reagan acknowledged the ethically unjust and unconstitutional nature of the Japanese American incarceration period during World War II through an official government apology and redress.

Thirty-four years after its closure, the site of the former Minidoka War Relocation Center was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Nearly a decade later, in the wake of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Manzanar was designated a National Historic Site. Rohwer was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1992; followed by Amache (Granada) and Tule Lake in 2006, and Heart Mountain and Topaz in 2007. In 2001, Minidoka was designated as National Monument and in 2008, it was re-designated as the Minidoka National Historic Site. In 2008, Tule Lake was designated as a National Monument; in 2015, Honouliuli was designated a National Monumnet in 2019 and redesignated as a National Historic Site.

Overseen and operated by the National Park Service, the sites at Manzanar, Tule Lake, and Minidoka were examined by NPS archeologist Jeff Burton and his team between 1993 and 1999, along with the seven other historic prison camps, as well as isolation and detention centers associated with Japanese American incarceration. The product of their work, a comprehensive report entitled Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites, examined the extant remains at these sites. With the help of old photographs and blueprints, it also synthesized the surveys to recommend all sites for either National Register of Historic Place or National Historic Landmark status.

Because most of the barracks and other buildings had long since been removed from the site, archeologists were not sure what they would find. During an excavation at Manzanar, archeologists were surprised to discover ceramic fragments, flower wire, bottles, and even the remnants of rock gardens built by incarcerees. The artifacts found on site reveal how incarcerees adapted to forced confinement. Archeological studies conducted at the sites uncovered many building foundations, which have aided in reconstructing the topography of the incarceration camps.

Archeological efforts of the NPS have in recent years been supplemented by university researchers and community groups interested in reclaiming the history of prison camps. The sites at Kooskia and Amache have been excavated by archeologists from the Universities of Idaho and Denver respectively, preserving the history of nearly forgotten camps in Idaho and Colorado. In addition, both NPS and university archeology programs have encouraged locals and the Japanese American commuity to participate. Manzanar hosts a Public Archeology programs annually during which volunteers aid in the excavation, restoration, and preservation of the site.

Development continues, with numerous plans to create and expand resources at the incarceration camps. The history of the Japanese American incarceration camps remains alive through preservation efforts in the hopes that this dark moment in American history will be neither forgotten nor repeated.

Tags

- manzanar national historic site

- minidoka national historic site

- tule lake national monument

- archeology

- archaeology

- asian american

- japanese

- minidoka relocation center

- manzanar national historic site

- manzanar war relocation center

- manzanar

- excavation

- california

- idaho

- tule lake

- pacific west region

- asian american and pacific islander heritage