Last updated: July 1, 2018

Article

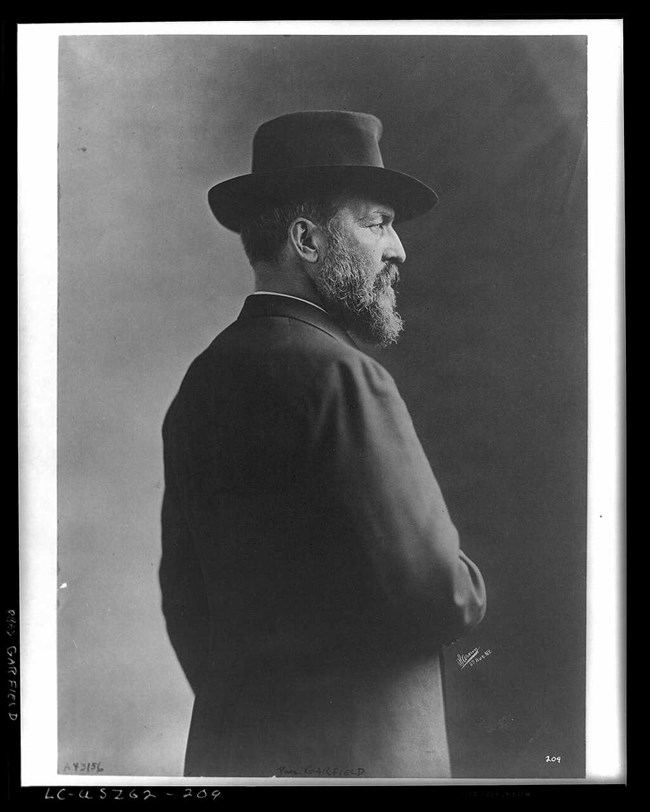

James Garfield: The Great "What If" President

Library of Congress

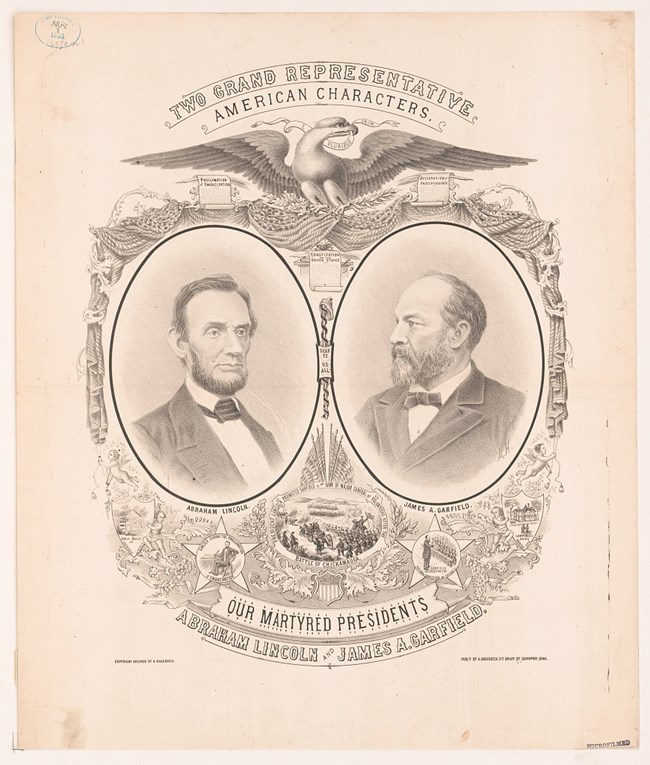

Of the four assassinated presidents, James Garfield is the least recognized. Kennedy’s administration was televised. McKinley was in his second term following the Spanish-American War. And Lincoln was, well, you know... Lincoln? But Garfield falls into that hazy, post-Reconstruction period where nothing much seems to be going on; no war, no global economic or social crisis, no real era-identifying issue. And that’s a shame, because, brief though Garfield’s time was, it was still productive and he confidently set out to steer a recalibrated country towards the modern era.

The last president to be born in a log cabin, James Garfield was born near Cleveland, Ohio, on Nov 19, 1831. Two years later his father died and he was raised by his single mother in straitened circumstances. Regardless of their poverty, she scraped enough money together to send her bookish son to school and then to college. Highly intelligent, after three years in college he out-learned all of his teachers, graduated with honors, and was a teacher himself before becoming a lawyer. In 1858 he married Lucretia Rudolph and the following year was elected to the Ohio State Senate. He served in the Civil War as a major general and saw action at Middle Creek, Shiloh, and Chickamauga. In 1863 he was elected to the House of Representatives where he served until 1880. When he was elected president, Garfield became the first, and thus far the only, president to come directly from the House.

Library of Congress

As Garfield entered the White House, he thought about Lincoln’s death 16 years before but considered it had been a fluke of the Civil War now long over, writing, “Assassination can no more be guarded against than death by lightning; and it is not best to worry about either.” He instead got right to work with his ideas on how he wanted to lead the country.

A desire to increase trade and influence with Latin America was near the top of his list, as was spreading the country’s influence wider in the world with commercial treaties with Korea and Madagascar. In conjunction with that, he looked into modernizing and expanding the navy. While a member of the House of Representatives, he had supported the abolition of slavery and praised the passage of the 15th Amendment granting black men the right to vote, and as president, he continued to advocate for civil rights. He proposed government-funded education to improve the lives of African Americans, especially in the South, and appointed several blacks to prominent federal positions, including Frederick Douglass as the District of Columbia recorder of deeds and Blanche Bruce as Register of the Treasury.

But at the top of his presidential to-do list was civil service reform, an issue lawmakers had been struggling to solve since the Grant administration and had led to the fracturing of the Republican Party, the party in power. Party patronage, also known as the spoils system, was the unofficial ruler of politics. It meant jobs were given not to merited applicants but to supporters of winning candidates, whether they were appropriate for the position or not. As a result, politicians were hounded for jobs by anyone and everyone. Garfield hated it. He found it wearying and a distraction from real business. “The personal aspects of the presidency are far from pleasant. Almost every one [sic] who comes to me wants something which he thinks I can and ought to give him, and this embitters the pleasure of friendship.” He was pursued on the street, in his office, and at home; his carriage rides were frequently interrupted; no place was safe from the office seeker. “I shall be compelled to live in great social isolation.” To be in control of the patronage was to hold a lot of the power. Unsurprisingly, corruption was rife.

At the head of the corruption pack was New York Senator Roscoe Conkling who tried to use his influence to pressure Garfield to appoint Conkling-approved individuals to lucrative positions. Garfield not only refused, he stood his ground, which resulted in a showdown in the Senate chamber. It ended with Conkling resigning after he realized the steadfast president now had more support behind him and was the one who held the power.

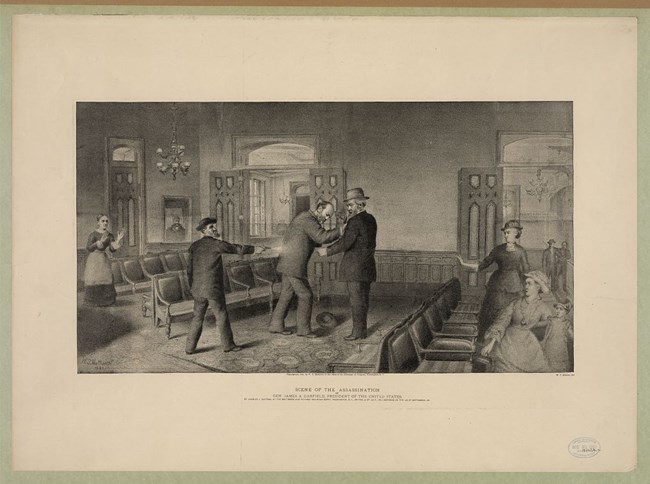

Library of Congress

One person who did support Conkling’s beloved spoils system was lawyer-theologian-writer-bill collector-commune member-drifter Charles Guiteau. Guiteau believed he was owed a consul position because of a speech he had given to a small gathering during Garfield’s campaign. When he felt he was being slighted by the president and not properly “rewarded”, he decided to take matters into his own hands.

On the morning of July 2, 1881, Garfield was looking forward to heading out to New Jersey for a much-needed vacation. As he and Secretary of State James Blaine walked into the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, along present-day Constitution Avenue NW between 6th and 7th streets, the quietness was broken by a loud, sharp clap. A bullet hit Garfield in the back, shattered a rib, and pierced his abdomen. He yelled out, “My God! What is this?” and fell to the floor, semi-conscious. Guiteau was immediately arrested and taken to jail.

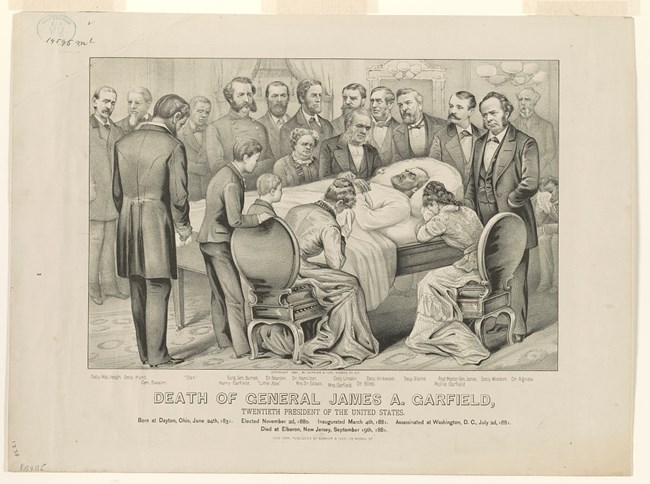

Library of Congress

Garfield was transported back to the White House for examination. In an attempt to find the bullet, doctors probed the wound with their unwashed fingers. The once-normal practice was slowly on its way out due to Louis Pasteur’s relatively recent germ theory and Joseph Lister’s recommendations of washing hands and using sterilized instruments. These recommendations were working their way through Europe, but had not yet fully caught on in America. All this poking and probing caused Garfield’s wound to hemorrhage and become inflamed. His body initially fought off the infections and he seemed to improve at first, but after two bed-ridden months of perpetual infections, it became obvious he was fading.

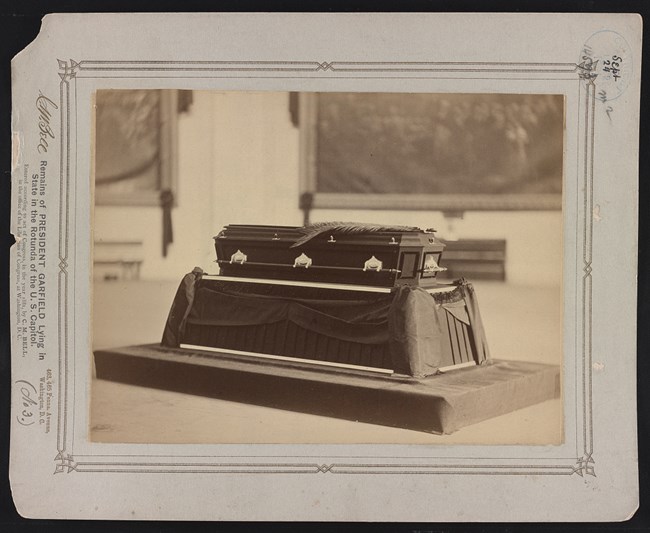

As he slowly died, his popularity across the country soared. Former president Rutherford Hayes wrote, “Garfield will now have a hold on the hearts of the people like that of Washington and Lincoln.” In early September, to escape the unrelenting heat and mugginess of the city, he was transported to the fresh air of his favorite seaside resort in Elberon, NJ, where, on September 19, 1881, he died. As the nation mourned, church bells tolled across the country.

Library of Congress

In 1882, Guiteau was found guilty of his crime and hanged. The following year, in honor of Garfield, President Chester Arthur brought about one of the most important reforms of the time, the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which did away with the spoils system and placed nearly 90,000 federal positions under a merit system administered by a new, independent Civil Service Commission. A large percentage of federal employees today have this act to thank for their jobs. (Like Park Rangers!)