Many of Lincoln's early attempts at emancipation focused on a policy of compensation. Slave owners would be paid by the Federal government to willingly give up their "property." As a test of the policy, compensated emancipation worked to a small degree in the District of Columbia.

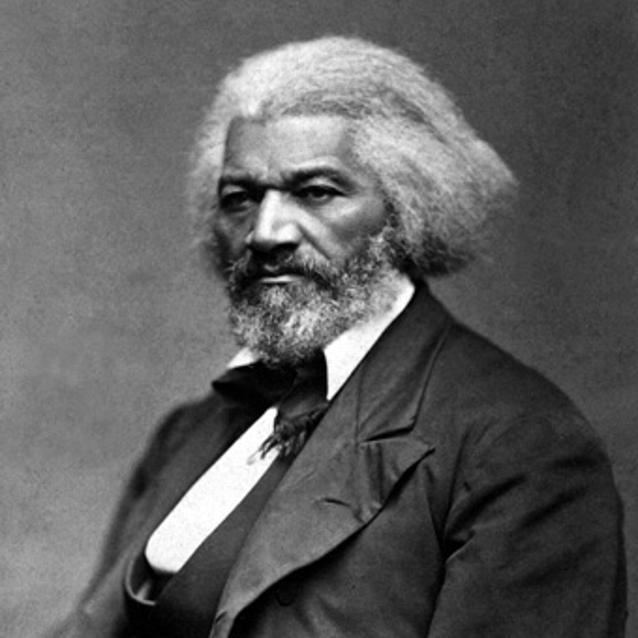

"The day dawns; the morning star is bright upon the horizon! The iron gate of our prison stands half open. One gallant rush from the North will fling it wide open, while four millions of our brothers and sisters shall march out into liberty." Frederick Douglass

Start with Washington

National Archives and Records Administration

The law went into effect on April 16th, 1862, and freed 3,100 people. The Federal government paid almost one million dollars to compensate slaveholders who took a loyalty oath to the United States. Money was also paid directly to some of the freed people as encouragement for them to emigrate to Africa or the Caribbean.

While no longer enslaved, African Americans in Washington, D.C. were far from equal citizens. It would take a century of struggle and many defining moments, such as the March on Washington in 1963, to secure the "blessings of liberty" and civil rights for all; a struggle that continues today. Emancipation Day, April 16th, is still an official holiday in the District of Columbia. Every year citizens celebrate freedom and remember those that worked and sacrificed to make it a reality.

An Opportune Moment?

Library of Congress

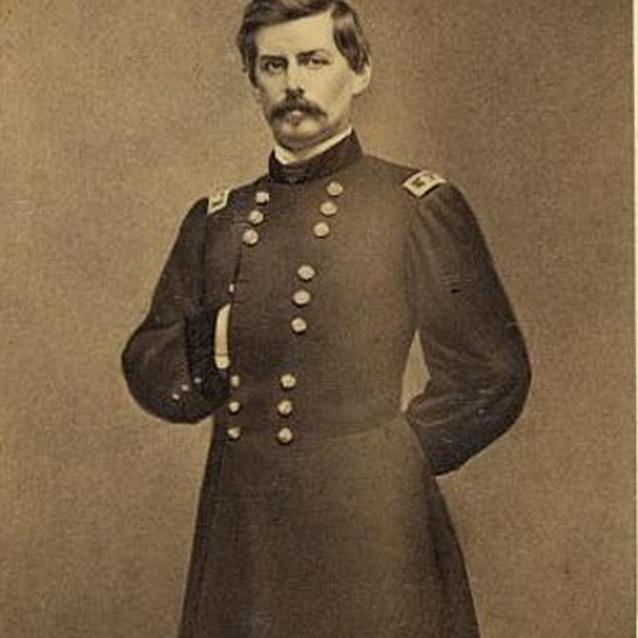

In late August 1862, Union Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia clashed with Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at the Second Battle of Manassas. Lee's audacity and Pope's mismanagement combined for a spectacular Union defeat. With the Union army forced to withdraw to Washington, D.C. and reorganize under Gen. George B. McClellan, the Confederates used the opportunity to invade Maryland and turn the war in their favor by intimidating northern civilians and earning international recognition. The Maryland Campaign was a setback for Lincoln and the Union. Under this kind of pressure, issuing an Emancipation Proclamation could give the impression of desperation Seward had warned him about. Lincoln chose to wait longer, hoping that somewhere in Maryland, the Union army would win a victory and alter the course of the war.

A House Divided

Library of Congress

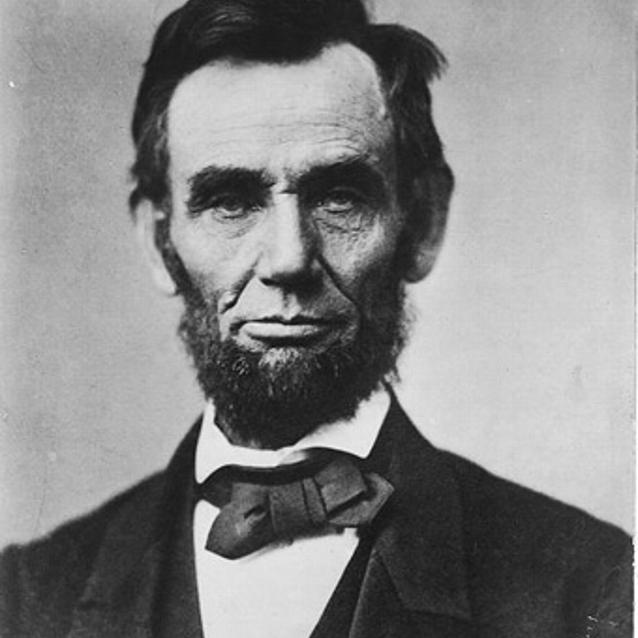

Before the war, Abraham Lincoln said,"I believe this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free." One might wonder what James Robinson thought of that statement. After all, his own family was half slave and half free. As a free man, Robinson worked hard to establish himself as a farmer and businessman in the Manassas area. Eventually marrying a slave woman, Robinson made deals to ensure the safety of his wife and children. He bought his son, Tasco. Later his wife and two daughters were freed when their owner died. Unfortunately, two other sons were sold South. One of them, James, was never heard from again.

Not just once, but twice, major battles were fought on Robinson's farm. Refusing to abandon what he had worked so hard for, he stayed and witnessed both battles.

Convinced that a victorious South would imperil his status as a freedman, Robinson held strong Union sympathies. However, his loyalty afforded him little protection from the ravages of war. During the Second Battle of Manassas, Federal forces commandeered Robinson's house and farm and forced Robinson to serve as a guide on the battlefield. During the battle, Union corps commander Franz Sigel used the house as his headquarters, and when the general vacated the dwelling, it became an aid station for the wounded. Also, Federal troops carried off the Robinson family's livestock, crops, provisions, and household furniture. Robinson had asked a Union officer for a guard for the premises, but "he paid no attention to me in the world." After the war, Robinson filed a claim with the Federal government for compensation for his lost and damaged property. He won partial restitution, in the amount of $1,249. With his personal liberty secure after the war, Robinson expanded his house, enlarged the farm, and became a prominent member in the now-free African American community.

Part of a series of articles titled Born of Earnest Struggle.

Previous: The Changes Were Starting

Next: Keeping It Together

Tags

Last updated: February 4, 2015