Last updated: March 25, 2022

Article

The Unique Role of Iroquois and Cree Employees at Fort Vancouver

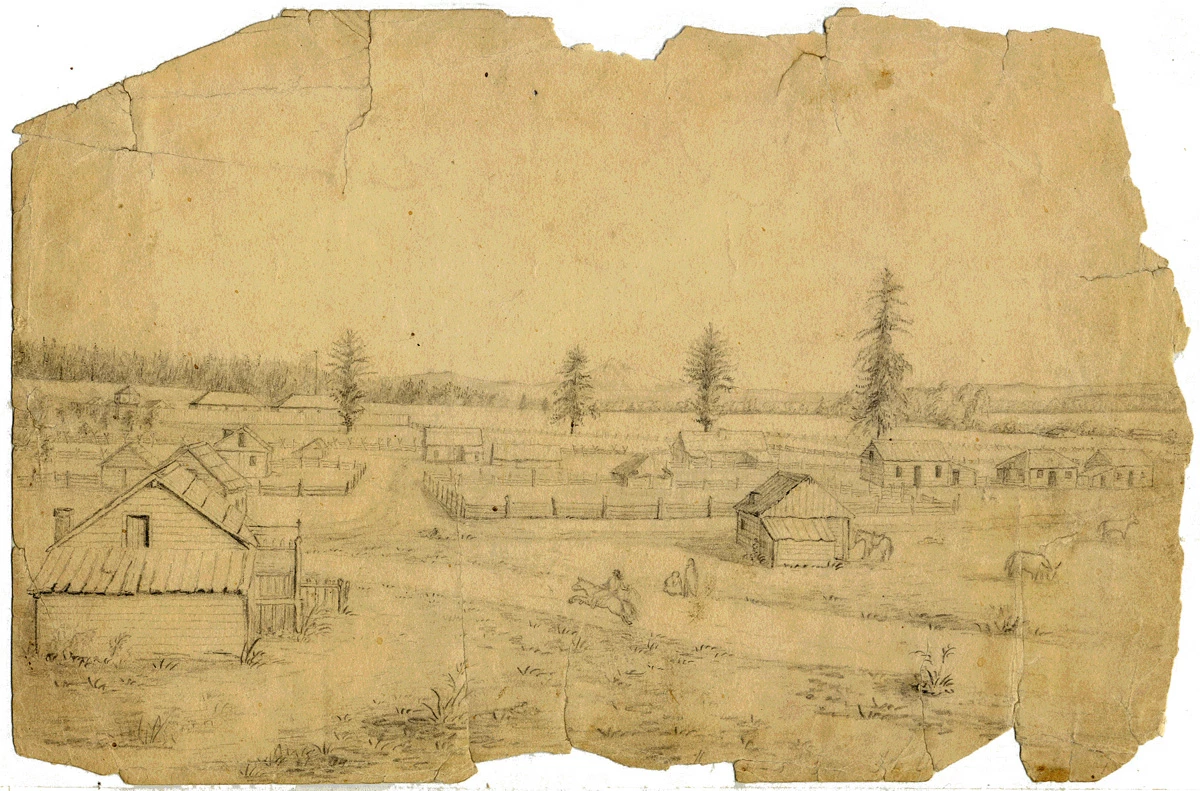

NPS Photo

Excerpted and adapted from An Ethnohistorical Overview of Groups with Ties to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, by Douglas Deur. Contact us for a PDF of the full report.

Throughout the journals, correspondence, and other chronicles of life at Fort Vancouver, there are innumerable passing references to both Cree and Iroquois residents and employees of the fort. The paths by which the two populations arrived at Fort Vancouver were very different, yet both played critical roles in HBC operations. To understand how both of these native peoples of Canada arrived at the fort, one must consider the history of both the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company.

The Cree traded actively with the HBC beginning very early in that Company’s history, and gradually took on roles as trappers for the Company. Simultaneously, for well over a century prior to the development of Fort Vancouver, the policy of encouraging intermarriage with native communities had been tested and developed squarely within the heart of traditional Cree territory. By the time that the HBC had ventured into the Pacific Northwest, the Company employees included a population of Cree descendents who were, in some cases, more than fourth-generation descendents of the original cross-cultural marriages between Cree and Euro-Canadian Company employees.

New Cree employees were being recruited constantly throughout much of the Company’s operations north of the 49th parallel in the early 19th century, and some portion of this population was recruited to assist in the early development of operations in the Columbia Department. Often, these individuals were among the most experienced fur traders available to the Company. Certain areas, such as James Bay and York Factory were places of active recruitment during this period, but innumerable small forts and posts dotted Cree territory and recruitment appears to have been restricted to no one portion of the HBC domain. Accordingly, the “Cree” of Fort Vancouver originated from HBC posts from throughout Canada – especially though not exclusively those of the Laurentian Plateau.

Individuals of Cree ancestry are mentioned frequently, if parenthetically, in fort records, though they are not generally discussed as a discrete population by early writers – probably reflecting their integration into the ranks of HBC employees to a degree that was distinctive among its native cohort. Many of these employees appear to have been among the undifferentiated population of “mixed-blood” or “Canadian” Métis reported in association with the fort, and it is unclear whether many of these individuals would have considered themselves “Cree” or some alternative designation.

Cree and part-Cree individuals are mentioned in Catholic church records at Fort Vancouver, and “Cree” children were among those reported at the Fort Vancouver school in the 1830s. Cree was among the languages recorded by visitors at Fort Vancouver, though remarkably little is said about its users, while a few Cree elements, documented within Chinook Jargon, suggest the historical use of this language at the fort. Those Cree men who worked at the fort sometimes stayed in the region after retirement, though it appears that many Cree employees moved to Canada after the dissolution of Fort Vancouver.

The modern Cree are composed of numerous constituent First Nations, spread from the Atlantic coast of Canada to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, in the provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, Saskatchewan, and Alberta as well as the Northwest Territories. In this context, the documentation of “tribal affiliation” for any individual of Cree ancestry associated with Fort Vancouver would require detailed biographical research.

In response, the North West Company established a practice of recruiting native labor from elsewhere within its operations. The lower Columbia, with its large, hierarchical tribal communities, each skilled in trade and negotiation, was as challenging a case as any that the Company had previously encountered. Within less than two years of trading from Fort George, Company staff determined that outside native labor was needed.

Beginning in 1815, the North West Company began recruiting Iroquois labor with trapping, hunting, and boating experience from the vicinity of its headquarters in Montreal and sending them to their operations on the lower Columbia River. The HBC had also been recruiting a modest number of Iroquois employees previous to the construction of Fort Vancouver, though by no means on the scale of its Montreal-based competitor. By the time that the HBC and the North West Company merged in 1821, both companies had been actively recruiting Iroquois labor for their work in the Columbia Department.

The Iroquois were also intended to reach out to the tribes of the Columbia River region to aid in their recruitment into the fur trade as labor, and to aid in teaching them the skills of commercial trapping – challenging tasks, at which the Iroquois men had mixed success. Efforts at Iroquois outreach to resident tribes were often unsuccessful, and conflicts between Iroquois employees and resident tribes are reported in the journals at least as much as successful interactions. Still, a few sources attribute some of the successes of Catholic missionization of Columbia basin Indians on the presence of the largely Catholic Iroquois as role models.

As a large and ethnically distinct component of the HBC employee population – ostensibly the largest discrete tribal community within the ranks of the HBC’s core group of employees – the Iroquois were a source of concern to many of the Company’s Anglo-Canadian leadership. They often operated under different assumptions than the HBC leadership, and maintained a sense of internal loyalty that sometimes appears to have trumped their loyalties to the Company and its Anglo-Canadian leadership.

Within the correspondence of John McLoughlin and other Company employees, there is a suggestion that certain Iroquois employees held resentment for Company management and that there was fear of potential mutiny. In 1855, Alexander Ross claimed that “The Iroquois were good hunters, but plotting and faithless." In 1842, McLoughlin suggested that “…the Iroquois…in General are always Ready for mischief." The HBC leadership made efforts to monitor and punish what they perceived as infractions, and almost never organized major operations in a manner that success was contingent on strict Iroquois adherence to Company plans. The HBC made occasional efforts to cap Iroquois numbers in the Columbia Department, but their effectiveness as trappers, hunters, boatmen and guides still placed them in high demand and they were therefore a persistent and major component of the HBC workforce on the Lower Columbia from the 1810s through the late 1840s.

Simultaneously, little specific information regarding the precise origins of the Iroquois men at Fort Vancouver can be found in written accounts from the fort. The men first arriving on the lower Columbia, according to Alexander Ross were “chiefly men from the vicinity of Montreal.” To understand the origin of these men, one must instead look into the broader history of the North West Company and, to a lesser degree, the Hudson's Bay Company.

The North West Company, at the time of the establishment of their Columbia basin operations, recruited labor most actively in a handful of Indian communities in close proximity to their Montreal headquarters. Many of the Iroquois recruits appear to have been associated with the Caughnawaga area, immediately across the Saint Lawrence River from Montreal. There is much evidence to suggest that the Iroquois employed in the Northwest were in some manner associated with the Jesuit Caughnawaga Mission at that location.

Other Iroquois populations that were frequently recruited into western ventures were the Oka and St. Regis communities, sitting a few kilometers’ distance east and south of Montreal respectively. Other Iroquois communities may have contributed a few individuals to the fur trade efforts on the Pacific coast, but the few communities listed above appear to have been the principal source for the vast majority of Iroquois labor during the period of active recruitment to the Columbia Department.

Recent sources suggest that the Iroquois of the lower Columbia were derived “from peoples now confined to the Kahnawaké, Kanesataké, and Akwesasne reserves and reservations in present-day Quebec and New York State” (Lang 2008: 91). This claim appears to match the historical evidence found in older sources. Kahnawaké – or more properly the Kahnawaké Mohawk Territory – is located at the site of the Caughnawaga Mission near Montreal. Kanesataké – or more properly the Kanesataké First Nation – is centered near the Oka settlement, also near Montreal. Akwesasne – or, more properly, the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne – is associated with the St. Regis community south of Montreal, and has a traditional territory that straddles the international boundary; their “St. Regis Mohawk Reservation” is located in far northern New York state while their “Mohawk Council of Akwesasne” is located across the international boundary in Quebec. All three of these communities are participants in the traditional governing body, the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs, which is itself a member organization of the Iroquois League or “Haudenosaunee.”

It is important to note that many of the Iroquois working on the lower Columbia River did not return home to eastern Canada. While single men often moved on to other HBC posts after the dissolution of Fort Vancouver, a significant number of the Iroquois working in the fort married into native or Métis families. Many of the frontier Iroquois labor ultimately found “homes in Métis settlements on Indian reservations established in the United States from 1856 onward” (Lang 2008: 93). Many of these families ultimately stayed in the Pacific Northwest. Individuals of Iroquois descendents found their way to Pacific Northwest reservation communities, such as the Grand Ronde Reservation; following the 1850s, some Métis of Iroquois ancestry were ultimately absorbed by the larger Anglo-American community of the Pacific Northwest.

Throughout the journals, correspondence, and other chronicles of life at Fort Vancouver, there are innumerable passing references to both Cree and Iroquois residents and employees of the fort. The paths by which the two populations arrived at Fort Vancouver were very different, yet both played critical roles in HBC operations. To understand how both of these native peoples of Canada arrived at the fort, one must consider the history of both the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company.

Cree Employees of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Cree people are inextricable from the history of the Hudson’s Bay Company. From the beginnings of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s operations in North America in 1670, it operated within Cree territory. The shoreline of Hudson Bay proper consisted significantly of Cree territory, as did adjacent lands of the Canadian interior east and west of the bay. Indeed, the term “Cree” is generally applied to Algonquian-speaking people whose traditional territories have ranged from Atlantic Canada to the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains in Canada.The Cree traded actively with the HBC beginning very early in that Company’s history, and gradually took on roles as trappers for the Company. Simultaneously, for well over a century prior to the development of Fort Vancouver, the policy of encouraging intermarriage with native communities had been tested and developed squarely within the heart of traditional Cree territory. By the time that the HBC had ventured into the Pacific Northwest, the Company employees included a population of Cree descendents who were, in some cases, more than fourth-generation descendents of the original cross-cultural marriages between Cree and Euro-Canadian Company employees.

New Cree employees were being recruited constantly throughout much of the Company’s operations north of the 49th parallel in the early 19th century, and some portion of this population was recruited to assist in the early development of operations in the Columbia Department. Often, these individuals were among the most experienced fur traders available to the Company. Certain areas, such as James Bay and York Factory were places of active recruitment during this period, but innumerable small forts and posts dotted Cree territory and recruitment appears to have been restricted to no one portion of the HBC domain. Accordingly, the “Cree” of Fort Vancouver originated from HBC posts from throughout Canada – especially though not exclusively those of the Laurentian Plateau.

Individuals of Cree ancestry are mentioned frequently, if parenthetically, in fort records, though they are not generally discussed as a discrete population by early writers – probably reflecting their integration into the ranks of HBC employees to a degree that was distinctive among its native cohort. Many of these employees appear to have been among the undifferentiated population of “mixed-blood” or “Canadian” Métis reported in association with the fort, and it is unclear whether many of these individuals would have considered themselves “Cree” or some alternative designation.

Cree and part-Cree individuals are mentioned in Catholic church records at Fort Vancouver, and “Cree” children were among those reported at the Fort Vancouver school in the 1830s. Cree was among the languages recorded by visitors at Fort Vancouver, though remarkably little is said about its users, while a few Cree elements, documented within Chinook Jargon, suggest the historical use of this language at the fort. Those Cree men who worked at the fort sometimes stayed in the region after retirement, though it appears that many Cree employees moved to Canada after the dissolution of Fort Vancouver.

The modern Cree are composed of numerous constituent First Nations, spread from the Atlantic coast of Canada to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, in the provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, Saskatchewan, and Alberta as well as the Northwest Territories. In this context, the documentation of “tribal affiliation” for any individual of Cree ancestry associated with Fort Vancouver would require detailed biographical research.

The North West Company and the Iroquois

The Iroquois arrived by a different path, and in response to different pressures. As the North West Company advanced into new portions of North America, it encountered frequent difficulties in recruiting local native labor. Local Indians generally possessed loyalties to their villages, tribes, and families that trumped their loyalties to the Company; moreover, they were often pulled away from Company duties to aid their communities in hunting and fishing, ceremonies, and other activities that competed with Company goals.In response, the North West Company established a practice of recruiting native labor from elsewhere within its operations. The lower Columbia, with its large, hierarchical tribal communities, each skilled in trade and negotiation, was as challenging a case as any that the Company had previously encountered. Within less than two years of trading from Fort George, Company staff determined that outside native labor was needed.

Beginning in 1815, the North West Company began recruiting Iroquois labor with trapping, hunting, and boating experience from the vicinity of its headquarters in Montreal and sending them to their operations on the lower Columbia River. The HBC had also been recruiting a modest number of Iroquois employees previous to the construction of Fort Vancouver, though by no means on the scale of its Montreal-based competitor. By the time that the HBC and the North West Company merged in 1821, both companies had been actively recruiting Iroquois labor for their work in the Columbia Department.

Iroquois Employees at Fort Vancouver

The reasons for recruiting Iroquois labor, specifically, among the pool of potential outside native laborers were numerous. The Iroquois had themselves experienced the effects of the fur trade in their homeland generations before arriving in the Pacific Northwest, including many of the fur trade’s corrosive effects, but had been integrated into the fur trade economy and were now enlisted as its agents in distant lands. Iroquois labor had been an effective vanguard of the North West Company as it expanded its operations in the Canadian Shield and Canadian Prairies. The Iroquois were accomplished boatmen, hunters, and were noted as early masters at the use of steel traps for beaver and other fur-bearers. Many early writers seem impressed by the strength, courage, and frontier competence of the Iroquois that they encountered working for Fort Vancouver. Naturalist David Douglas, for example, made reference to Iroquois working as capable hunters, guides, and boatmen in the region. Iroquois were often depicted as intrepid field men, being numerous among the first fur trapping expeditions into the Snake Country, Willamette Valley, and southern Oregon.The Iroquois were also intended to reach out to the tribes of the Columbia River region to aid in their recruitment into the fur trade as labor, and to aid in teaching them the skills of commercial trapping – challenging tasks, at which the Iroquois men had mixed success. Efforts at Iroquois outreach to resident tribes were often unsuccessful, and conflicts between Iroquois employees and resident tribes are reported in the journals at least as much as successful interactions. Still, a few sources attribute some of the successes of Catholic missionization of Columbia basin Indians on the presence of the largely Catholic Iroquois as role models.

As a large and ethnically distinct component of the HBC employee population – ostensibly the largest discrete tribal community within the ranks of the HBC’s core group of employees – the Iroquois were a source of concern to many of the Company’s Anglo-Canadian leadership. They often operated under different assumptions than the HBC leadership, and maintained a sense of internal loyalty that sometimes appears to have trumped their loyalties to the Company and its Anglo-Canadian leadership.

Within the correspondence of John McLoughlin and other Company employees, there is a suggestion that certain Iroquois employees held resentment for Company management and that there was fear of potential mutiny. In 1855, Alexander Ross claimed that “The Iroquois were good hunters, but plotting and faithless." In 1842, McLoughlin suggested that “…the Iroquois…in General are always Ready for mischief." The HBC leadership made efforts to monitor and punish what they perceived as infractions, and almost never organized major operations in a manner that success was contingent on strict Iroquois adherence to Company plans. The HBC made occasional efforts to cap Iroquois numbers in the Columbia Department, but their effectiveness as trappers, hunters, boatmen and guides still placed them in high demand and they were therefore a persistent and major component of the HBC workforce on the Lower Columbia from the 1810s through the late 1840s.

Modern Ties to the Iroquois Community

Discerning the identity of modern Iroquois descendents tied to the Fort Vancouver community is challenging. Iroquois men intermarried with Cree and Métis extensively prior to moving into the Pacific Northwest, while French voyageurs had married Iroquois women occasionally too; the children of these unions often took positions in the fur trade and were categorized as Iroquois, Métis, or other designations - often depending on the predilections of the individual chronicler. Moreover, many Iroquois working for the Company took on the surname “Iroquois” apparently due to the fact that their supervisors could not pronounce their Iroquois names.Simultaneously, little specific information regarding the precise origins of the Iroquois men at Fort Vancouver can be found in written accounts from the fort. The men first arriving on the lower Columbia, according to Alexander Ross were “chiefly men from the vicinity of Montreal.” To understand the origin of these men, one must instead look into the broader history of the North West Company and, to a lesser degree, the Hudson's Bay Company.

The North West Company, at the time of the establishment of their Columbia basin operations, recruited labor most actively in a handful of Indian communities in close proximity to their Montreal headquarters. Many of the Iroquois recruits appear to have been associated with the Caughnawaga area, immediately across the Saint Lawrence River from Montreal. There is much evidence to suggest that the Iroquois employed in the Northwest were in some manner associated with the Jesuit Caughnawaga Mission at that location.

Other Iroquois populations that were frequently recruited into western ventures were the Oka and St. Regis communities, sitting a few kilometers’ distance east and south of Montreal respectively. Other Iroquois communities may have contributed a few individuals to the fur trade efforts on the Pacific coast, but the few communities listed above appear to have been the principal source for the vast majority of Iroquois labor during the period of active recruitment to the Columbia Department.

Recent sources suggest that the Iroquois of the lower Columbia were derived “from peoples now confined to the Kahnawaké, Kanesataké, and Akwesasne reserves and reservations in present-day Quebec and New York State” (Lang 2008: 91). This claim appears to match the historical evidence found in older sources. Kahnawaké – or more properly the Kahnawaké Mohawk Territory – is located at the site of the Caughnawaga Mission near Montreal. Kanesataké – or more properly the Kanesataké First Nation – is centered near the Oka settlement, also near Montreal. Akwesasne – or, more properly, the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne – is associated with the St. Regis community south of Montreal, and has a traditional territory that straddles the international boundary; their “St. Regis Mohawk Reservation” is located in far northern New York state while their “Mohawk Council of Akwesasne” is located across the international boundary in Quebec. All three of these communities are participants in the traditional governing body, the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs, which is itself a member organization of the Iroquois League or “Haudenosaunee.”

It is important to note that many of the Iroquois working on the lower Columbia River did not return home to eastern Canada. While single men often moved on to other HBC posts after the dissolution of Fort Vancouver, a significant number of the Iroquois working in the fort married into native or Métis families. Many of the frontier Iroquois labor ultimately found “homes in Métis settlements on Indian reservations established in the United States from 1856 onward” (Lang 2008: 93). Many of these families ultimately stayed in the Pacific Northwest. Individuals of Iroquois descendents found their way to Pacific Northwest reservation communities, such as the Grand Ronde Reservation; following the 1850s, some Métis of Iroquois ancestry were ultimately absorbed by the larger Anglo-American community of the Pacific Northwest.