Last updated: December 10, 2024

Article

Collaboration & Innovation For Ecosystem Restoration in the Southwest

NPS / Tani Hubbard

Curbing a voracious, amphibious predator using science

In the expansive wilderness of America's southwest, a potent threat looms – or croaks: invasive bullfrogs. While seemingly harmless, the presence of the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) disrupts fragile wetland ecosystems and poses a significant danger to native amphibian species.

Even though they’re called ‘American’ bullfrogs, they are not native to the West; rather, they’re native to the Eastern United States, commonly found in states east of the Mississippi River. The response to this ecological challenge is a collaborative project, with Inflation Reduction Act funds and multiple partnerships, to eliminate bullfrog populations and restore the balance of native species in eight southwest national parks.

So – what’s so bad about these bullfrogs? Their malice can be found in their appetite, presence, and ecosystem-wide effects: American bullfrogs are really hungry, they’re really dominant in their ecosystems, and they often carry some really nasty pathogens.

Both tadpoles and adult bullfrogs are known to consume the eggs of native fishes, reptiles, amphibians, water birds, and even small mammals. Once an invasive bullfrog population is established, they can compete directly with those native species for limited food resources. Additionally, park managers and recent research has found that these bullfrogs are hosts of chytrid fungus (specifically Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), fungi that can be deadly for some amphibians.

NPS Photo

“Control of bullfrogs is particularly difficult because they have high reproductive rates, they are voracious predators, and they can disperse across long distances.,” said Dr. Erin Zylstra, a quantitative ecologist for the Tucson Audubon Society and a close partner with this project. “We're hoping to build off the knowledge and experience of other groups tackling bullfrogs in Arizona (such as the University of Arizona, Arizona Game and Fish Department) to develop effective, site-specific solutions and establish long-term monitoring programs for aquatic species and systems moving forward.”

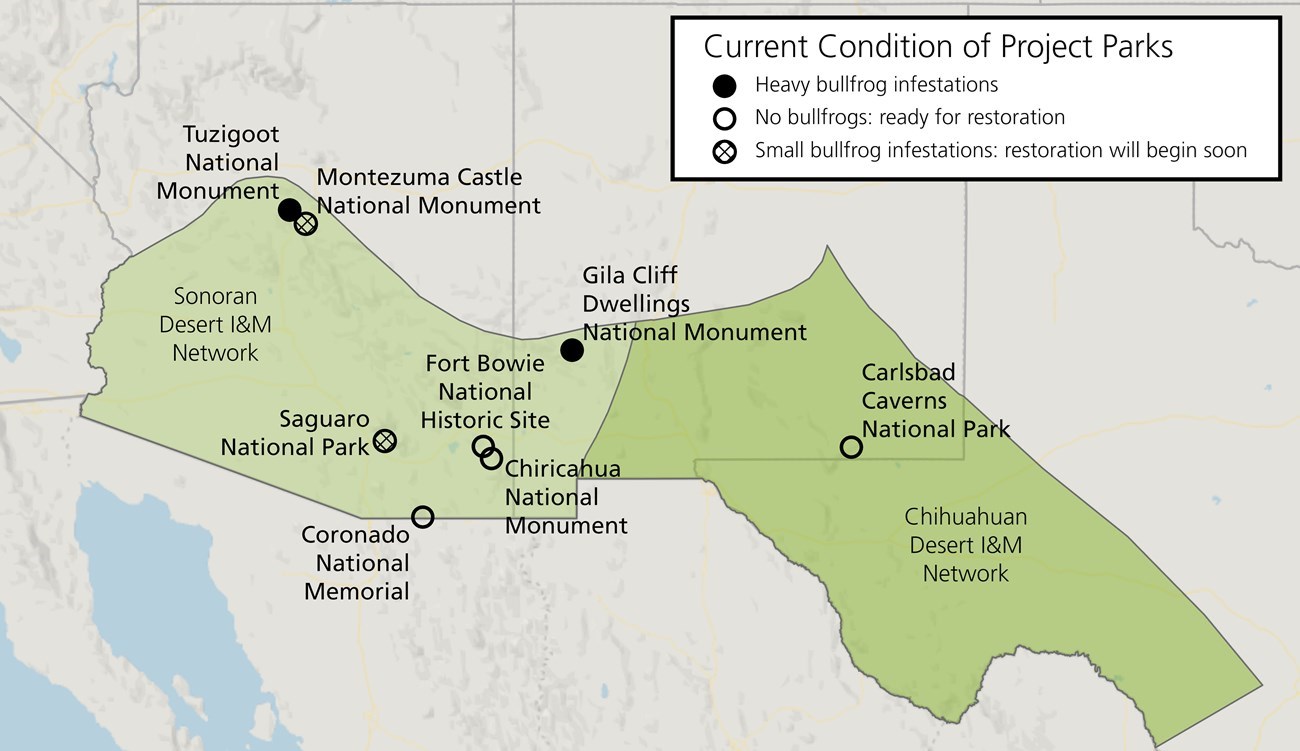

The project encompasses work at Carlsbad Caverns National Park, Chiricahua National Monument, Coronado National Memorial, Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, Montezuma Castle National Monument, Saguaro National Park, and Tuzigoot National Historical Park.

NPS / ELIZABETH SCHNAUBELT

When the bullfrogs are gone, it's harder for pathogens to continue thriving, and thus, no longer wrecking havoc on these Southwestern ecosystems.Therefore, the removal of these bullfrogs will relieve pressure on native amphibians and reptiles, encouraging the natural recovery of these wetlands.

“Invasive species are a neighborhood issue,” said Andy Hubbard, NPS Program Manager of the Sonoran Desert Network, and project lead. “In this case, it’s a really big neighborhood when we talk about the whole project area – and that ‘neighborhood’ includes parks, local and area residents, and a variety of non-profit conservation groups.”

Hubbard said project success depends on coordinating neighborhood skills. “It doesn’t make sense for us to go to a small park like Gila Cliff Dwellings and deal with ‘our’ local problem when there might be a large population of bullfrogs right next door. Those nearby bullfrogs would simply move into now-vacant habitat and we’ve solved nothing. The only way to do this is in a holistic, collaborative fashion with our partners,” Hubbard said.

Elizabeth Schnaubelt, a Sonoran Desert Network Scientist in the Park, has been integral to the public outreach side of the project. “The project has a long list of community partners, such as the Arizona Frog Team at the University of Arizona, other federal agencies and state departments, park neighbors and private landowners…the list goes on and on,” said Schnaubelt. “It's important to us that we have a relationship with all parties and work together to develop action plans that benefit everyone. We've had longstanding relationships with many of our partners, and park neighbors are the newest to our collaboration since they are uniquely involved with this project.”

NPS / Elizabeth Schnaubelt

Innovation Amidst Invasives: Using eDNA for Species Inventory

The battle against invasive species is ongoing, but with collaborative efforts and innovative approaches, the NPS and its partners are starting to see progress. The project's early stages focused on gathering baseline data, crucial to inform subsequent control and restoration efforts. Experienced herpetologists led traditional survey methods to detect bullfrog populations and assess native species' status across the project’s parks. The project added the innovative technique of gathering environmental DNA (eDNA)--noted by Hubbard as “a groundbreaking tool in the fight against invasive species.”

Using eDNA allows for water sampling that can match known DNA traces for target species such as bullfrogs, chytrid fungi, and ranaviruses. In this case, eDNA analysis allows researchers to identify not only bullfrog populations but also the native species present, including very rare or hard to detect native species. This technology, combined with acoustic recordings that capture distinctive mating calls, provided a multi-faceted approach to species monitoring and assessment.

“We have several sites where we did not detect some of our target species using traditional visual encounter surveys, but eDNA samples collected at the same time provided reliable detections of their current use of that wetland,” Hubbard said. “So, the eDNA helps us establish which sites need to be treated, which sites still have some of the native species as well as which sites are still currently being invaded by bullfrogs.”

NPS Photo

Spread the word to educate the neighborhood and beyond

Project team members chose diverse outreach strategies to alert the public to the bullfrog threat. From traditional media coverage to social media campaigns and educational materials like stickers and coloring books, efforts were made to raise awareness and foster community involvement. Public events and educational programs further enhanced engagement with park visitors and supporters, inspiring a sense of community stewardship for the parks and their native inhabitants.

“This project is one of those rare, funded opportunities to think big about conservation. Threats to native amphibians and reptiles in the southwest, particularly decreases in surface water availability and the spread of invasive species, are landscape-scale problems that require collaborative work from a number of partners,” said Dr. Zylstra. “The more diverse the group of collaborators (federal agencies, academic institutions, non-profits, local landowners), the more likely we are to develop effective strategies for species conservation, at both a local and regional scale.”

With this funding, project managers will be able to recruit and hire advanced graduate research scientists to lead native species recovery assessments and help the Arizona Frog Team develop site-specific bullfrog control and native species recovery plans. This team will continue to reach out to park neighbors to aid in public understanding of this niche issue – as well as raising awareness via social media and community gatherings – such as the recent Natural History of the Gila Symposium.

As the project continues to unfold under the leadership of National Park Service managers such as Andy Hubbard, park scientists like Elizabeth Schnaubelt, and local partners such as Dr. Erin Zylstra— this holistic project serves as a beacon of hope for the preservation of biodiversity in our nation's cherished national parks.

Ben is a current graduate student at Colorado State University, within the Journalism & Media Communication Masters of Science Program. He works as a BIL & IRA Science Communication Specialist with the National Park Service's Natural Resources Office of Communications. Apart from his work, Ben is a professional triathlete, with an affinity for adventures and exploration in the mountains.

Tags

- carlsbad caverns national park

- chiricahua national monument

- coronado national memorial

- fort bowie national historic site

- gila cliff dwellings national monument

- montezuma castle national monument

- saguaro national park

- tuzigoot national monument

- inflation reduction act

- ecosystem restoration

- science

- sonoran desert network

- chihuahuan desert network

- inventory and monitoring

- inventory and monitoring division