Artist and writer Mary Hallock Foote’s life was transformed in 1875 when she married Arthur DeWint (A. D.) Foote. As a civil and mining engineer, Arthur followed the mining boom throughout the American West, bringing along his new wife and growing family. By the time Mary arrived in Boise, Idaho, in 1884, she had accompanied Arthur from California to South Dakota, on to Colorado, and even to Mexico, as his entrepreneurial instincts drove him to various mining outfits. As the West’s early mining economy evolved to include agriculture, Arthur also pursued irrigation projects, and traveled to Boise to harness its river with his immense canal scheme—the New York Canal.

The Boise River, a tributary of the Snake River, drains westward out of the Sawtooth Range, where mountains rise to 10,000 feet. In the last 60 miles of its course to the Snake River, the Boise River passes through the Boise Valley, an area with great agricultural potential if it could be irrigated. Upon seeing the rushing Boise River, Mary described it as a “wild river” they had “come to tame.” Arthur envisioned building a long canal that would carry water to power mills, irrigate farm lands, and hydraulically mine gold. In A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West, Mary reflected on the sureness Arthur, her “dreamer,” felt about this grand project. Yet, for Mary, Idaho was merely “thousands of acres of desert empty of history.” Although many easterners romanticized the frontier, Mary unenthusiastically ventured west, leaving behind her beloved friends in New York. Despite this resistance, Mary’s art and writing came to reflect her western experiences, which fed Victorian curiosities in the East. The royalties from Mary’s work kept food on the table as her husband struggled to secure funds for his mining and irrigation project. After years of trying to secure financiers, and receiving enough funding from a group of New York investors—for which the canal is named— to build only the first 10 miles of the canal, Arthur lost hope in his venture, and in 1896, found long-term employment with a California mining company, moving the family further west. In 1905, the U.S. Reclamation Service purchased the canal and its water rights, which became the foundation of the Payette-Boise Project, the agency’s largest irrigation project at the time.

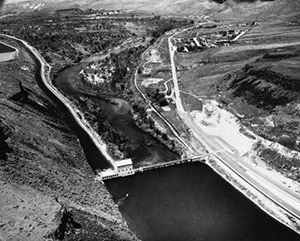

On December 27, 1905, the Secretary of the Interior authorized construction of the first components of Reclamation’s Payette-Boise Project. Surveyors labeled Boise Valley lands under two designations—“irrigated” or “desert.” Agency engineers concluded that they could irrigate 94,000 “desert” acres by building a large storage dam on the Boise River and by extending Foote’s New York Canal further west to a small reservoir they would build, Lake Lowell. A new diversion dam, the Boise River Diversion Dam, would channel water into the New York Canal.

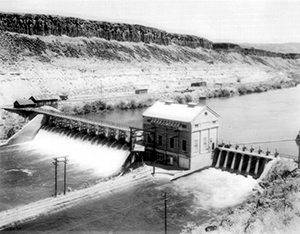

In 1906, Reclamation began constructing the Boise Diversion Dam and the new headworks for the New York Canal. On February 22, 1909, nearly 3,000 spectators lined up to watch water gush into the New York Canal at the Boise Diversion Dam. Two days later, the Idaho Statesman published an article penned by D. W. Ross, Reclamation’s chief engineer in Idaho, titled “A. D. Foote—An Appreciation.” Ross praised Foote’s progressive vision for the Boise River Valley that foresaw great irrigation works and populated farmland. Mary Hallock Foote recalled how her husband’s “broken work…came to its accomplishment, with the government behind it.” She pasted the clipping in her scrapbook and pondered “all we didn’t do in Idaho.”

At 40 miles long, the finally complete New York Canal directed river water to a series of ditches for irrigation. The remaining Boise River water that was not diverted continued over the diversion dam and down its natural channel, thus water constantly passed over the Boise Diversion Dam. This constant flow made the site ideal for a new project—a powerplant to fuel construction of the storage dam proposed by Reclamation engineers, later named Arrowrock Dam, to be built 22 miles upstream from the City of Boise.

Electricity was needed to power construction equipment, and light and heat buildings in the construction camps at the Arrowrock Dam site. Work on the Boise Diversion Powerplant began in June 1911, and it first delivered power in May 1912. The rectangular concrete building has a gabled roof, and four bays on the upriver and downriver sides, and three bays each on the other sides. Each bay contains a tall window, kept open to ventilate the spinning turbines. Two 17 mile-long, 23,000-volt transmission lines were also constructed to carry current generated at the powerplant to the Arrowrock construction site.

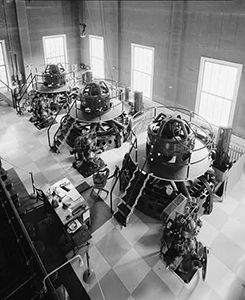

Like many mass-produced technologies in the early twentieth century, hydroelectric equipment had become standardized. Reclamation used uniform equipment for the Boise Diversion Powerplant, and had to design the powerplant building to fit the standardized equipment. Engineers also needed the equipment to fill the space resourcefully, as the power facility was constructed right into the dam itself, on the sliver of space between the river to the north and the New York Canal to the south. Because of these constraints, Reclamation chose the space-saving vertical double Francis turbines that used standardized wooden turbine bearings and belt-drive auxiliary systems. Reclamation used two former sluicing tunnels, which had originally been built to divert the river around the dam construction site, as discharge tunnels for two turbine units, requiring workers to excavate for the third unit only. Because Reclamation reused this space, engineers installed the equipment first, then finished the structure around it. Although constructing the powerplant directly in the dam was an efficient use of space, the design required engineers to cut penstock openings in the dam to allow water into the turbine pits for generation, potentially compromising the dam’s structural integrity. To counter this, they crafted special gates on the outside of the openings that, when closed, redistributed the upstream water pressure to the powerhouse foundation and walls.

Boise Diversion Powerplant generated 1,500 kilowatts, enough power to light 1,100 homes. After Arrowrock Dam’s completion in 1914, the powerplant supplied Boise Valley farms, homes, and other construction projects with its excess electricity. In a 1928 New Reclamation Era article titled “Electricity on an Irrigated Farm, Boise Project, Idaho,” author J. F. Bruins told how government electricity first brought lights, then a motored water pump, then a milk separator—all easing home and work life on the western farm.

However, the plant’s constant use—especially during the 1973 energy crisis—exhausted its original equipment, which became potentially unsafe to operate. Furthermore, parts needed to repair the equipment were often no longer mass produced and had to be custom manufactured at great cost. Therefore, in 1982, Reclamation put the timeworn powerplant on “ready reserve status,” meaning it would only be used when there was a high demand for electricity. When not in use, the penstock gates remained closed and water simply bypassed the plant and flowed down the river. However, in 2000, ever increasing power demand combined with energy shortages caused Reclamation and BPA to re-tap renewable hydroelectric energy by rehabilitating the Boise Diversion Powerplant to bring it back into steady service and by “uprating” other historic facilities.

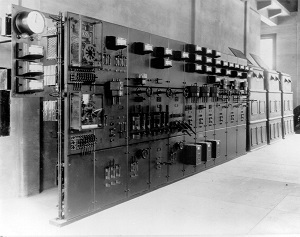

Reclamation took particular care to rehabilitate the Boise Diversion Powerplant in a way that preserved the features that defined the plant’s historic character, keeping the main floor of the plant essentially unchanged. The plan also improved the technology in an unobtrusive way by maintaining the double turbine configuration and installing the new generators within the original generator housings and behind the original slate control panels. For this reason, much of the plant still looks as it did in 1911. Due to advances in technology since the powerplant was constructed in 1911, the three new generators installed in the plant increased the generative capacity from 1,500 kilowatts to 3,300 kilowatts. The retrofit began in 2002 and the plant was returned to service in 2004, preserving the historic powerplant while maximizing its efficiency and safety.

Today, power generated at the Boise Diversion Powerplant is marketed by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), a Federal non-profit agency that delivers nearly one third of the power consumed in the Pacific Northwest. Power from Boise Diversion Powerplant serves BPA’s Southern Idaho Power System, and is among the oldest powerplants, along with the Minidoka Powerplant, in operation in the Pacific Northwest.

Transforming desert into farmland, shouldering unfinished canal schemes, and salvaging old technology for renewable energy contribute to the Boise Diversion Powerplant’s reclamation story. On March 15, 1976, the historic district comprising the Boise Diversion Dam, Powerplant, and Deer Flat Embankments that create Lake Lowell was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, recognizing the system’s significant contribution to the history of the Boise and Payette river valleys, and for its representation of early twentieth-century hydroelectric engineering design and technology.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017