Women from every part of the Creek Nation suffered from the war. As widows, refugees, and victims of terror they were forced to fend for themselves and construct new realities for their children.

In his memoirs, David Crockett described the desperation of one woman from the town of Tallahatchee, who sat in the door of her home, and, in a determined and desperate attempt at defense, fired an arrow at advancing Americans, killing one of them.

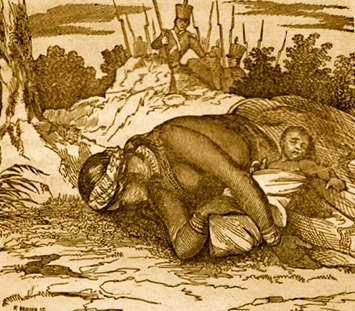

John Frost, A Pictorial Biography of Andrew Jackson by John Frost. New York: 1860.

In late November 1813, an American army led by General John Floyd attacked the Creek village of Autossee. Floyd’s army was one of three that descended on the Creek Nation in the late fall of 1813, after the civil conflict among the Creek people was transformed into an American-Creek War following the attack on Fort Mims by Red Stick Creeks. As the inhabitants of Autossee fled the invaders, Floyd’s men set the village on fire, destroying everything. Most of the inhabitants, including women and children, escaped with their lives, but with little else. The destruction of Creek settlements and villages continued throughout the winter into early spring. Some Creek became prisoners of the invading armies, while the majority became homeless refugees hiding in inaccessible cane breaks and remote locations far from the smoldering ruins of their homes and corn fields.

Women from every part of the Creek Nation suffered from the war. Some women lost their lives as casualties of the attacks, and some were specifically targeted for execution by one side or the other due to their family affiliation or for their own part in the growing conflict. Those forced to flee their homes as American troops advanced during the winter of 1813-1814 suffered greatly during due to lack of clothing, blankets, shelter, and adequate food.

Protecting the civilian population was a major problem for Creek defenders as the home front became a battleground. Many women and children were killed or severely wounded during battles. In his memoirs, David Crockett described the desperation of one woman from the town of Tallahatchee, who sat in the door of her home, and, in a determined and desperate attempt at defense, fired an arrow at advancing Americans, killing one of them. She was promptly killed in return by the advancing soldiers. Some captured Creek women—and their children—were enslaved. After the town of Hillabee was destroyed by a joint detachment of Americans and allied Cherokee warriors, many of the surviving women were taken back to Cherokee country as slaves. A few American soldiers, including Andrew Jackson, took possession of orphan Creek babies and young children, and sent them home as “petts” or companions for their own children.

The war that devastated the Creek country destroyed upwards of 50 towns and villages and left more than 2,000 warriors and an uncounted number of civilians dead. The war disrupted town life and agriculture, leaving the entire population homeless and without adequate food. By the time General Andrew Jackson oversaw construction of the fort that would bear his name and prepared to impose a peace settlement on the Creek nation, over 8,000 hungry Creeks were drawing government rations. Many were drawn to Fort Jackson, built in the center of the Creek Country in the summer of 1814. In a letter to his own wife, Andrew Jackson recounted the horrific plight of the Creek women he observed who were scavenging for grains of corn dropped from the mouths of his army’s horses. After the war, a handful of women who had been aligned with the National Council were able to obtain compensation for their property losses. But the majority were not so lucky and faced the task of rebuilding in a devastated country, a task made more difficult by the disproportionate loss of adult men in battle. Some Creeks simply fled, seeking refuge from further military action as permanent exiles in Florida.

Last updated: August 15, 2017