Last updated: May 8, 2024

Article

The History of the Spring Enclosure

NPS.

Historical archeology is often about testing assertions made in historical documents against physical remains in the archeological record. Historical archeologists often look at whether the archeological remains verify what is written, or tell a different story. If they do suggest something different than written accounts, what alternative version do they present and why might people have written down something else?

This process of verifying the written record was used to unravel and document the stone masonry of the spring enclosure at Fort Davis National Historic Site. Was the existing spring enclosure actually a reconstruction built in the 1940s? If it was a reconstruction, was it built in the original location? If there was some portion of the original masonry left, which portions were original and which were reconstructed? The resulting investigation illustrates the unique perspective that archeology can bring even to sites occupied relatively recently and the way it can provide information on aspects of peoples’ daily lives that aren’t discussed in detail in written accounts.

Fort Davis

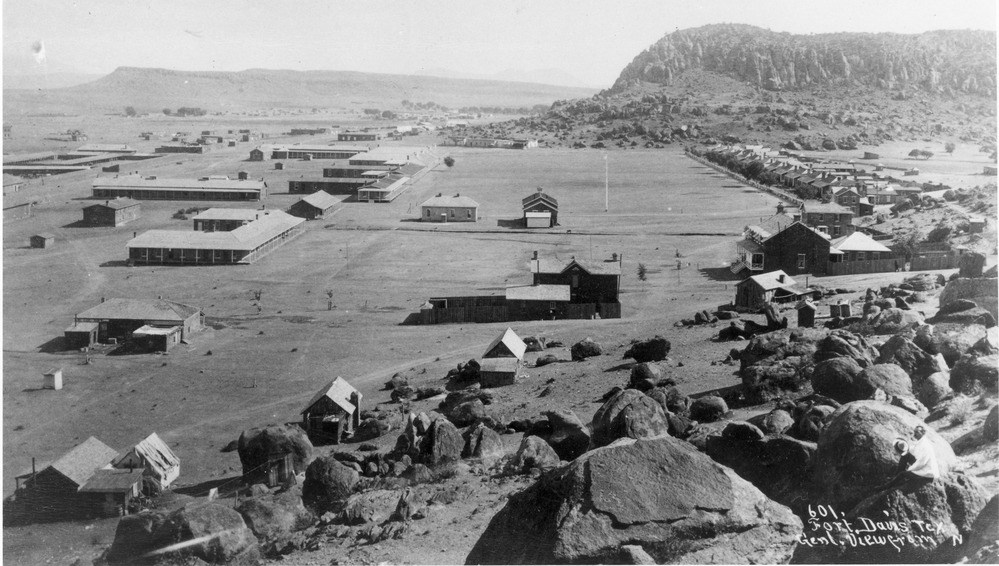

Situated near Limpia Creek on the eastern side of the Davis Mountains in western Texas, Fort Davis played a key role in the settlement and development of the western frontier. Established in 1854, the fort housed troops of the Eighth Infantry in their pursuit of Comanches, Kiowas, and Apaches. Texas seceded from the Union during the Civil War, and the Federal government evacuated the fort at that time. It was occupied by Confederate troops between 1861 and 1862 and though Union troops took possession in 1862, they left soon afterwards.

The fort lay deserted until the companies of the Ninth U.S. Cavalry reoccupied it. The Ninth U.S. Cavalry was an African American regiment that was formed after the Civil War. This regiment, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was active in securing the Southwest for American colonization. The African American troops began construction on a new fort, just east of the original site, and construction continued through the 1880s. With the end of the Indian Wars and in the wake of the army’s efforts to consolidate its frontier garrisons, Fort Davis was finally abandoned by the military in 1891.

Water at the Fort

As anyone familiar with the West knows, water is a precious and uncommon resource. In the early days of the fort, from the 1850s through the 1880s, water was hauled from the nearby Limpia Creek in mule-drawn wagons. In 1869, post officers urged that a spring near the fort be developed as an alternative to Limpia Creek, and it was used for several years. The spring was blamed for an outbreak of diarrhea, however and so hauling water in wagons recommenced. Several wells near the barracks and officers’ quarters were in place by 1872, and after a thorough cleaning, the spring that is the focus of this inquiry was once again in use in 1875.

At this point, according to the historical documents, a stone wall was raised around the spring, and a small pump was used. While this may have made water collection easier, the Post Surgeon, Ezra Woodruff, still had concerns about the water quality which he expressed in a communication to the Post Adjutant.

There is a defect in the fact that the water passes through to the wall below the surface and rises directly into the [adjacent] drainage ditch. The ditch...is the resort of pigs and I have observed them wallowing in it within six feet of the spring, besides being the receptacle of other rubbish. I would...suggest that the wall enclosing the spring should be made water tight by hydraulic cement, so that the water once escaped from the spring cannot flow back. I would also suggest that the ditch should be graded steeper so that the water should flow rapidly away and not be able to stand near the spring. I would also suggest that the spring be covered with boards & that a stone wall be built around it at a proper distance to prevent persons and animals from directly approaching the edge of the spring and dipping dirty vessels of all kinds directly into it.

There are no documents that specifically note that Surgeon Woodruff’s recommendations were implemented, but there is a clue in a contemporary description of the spring as being 10 by 13 feet in diameter and containing 6 feet of water, and in another that describes the spring as “walled up.” A period map shows the spring with irrigation ditches extending from the spring to the fort garden.

Photograph probably by Frank Higgins, courtesy of Fort Davis National Historic Site.

Big Plans for Fort Davis

Following the abandonment of the fort, many buildings fell into disrepair. A 1916 photograph of the spring enclosure shows only the western portion of the wall still standing. The interior is full of dirt and there is no evidence of water. In contrast, a photograph taken sometime around 1930 shows the interior of the spring cleaned of debris and full of water, though the wall had not been repaired. It seems highly likely that the clean-up efforts were conducted by Jack Hoxie, a movie man from Hollywood who saw Fort Davis as a business opportunity. Various articles in the local newspaper, the Alpine Avalanche, between 1929 and 1932 outline his plans to restore sections of the fort and build, in various combinations and to various specifications, a rodeo ground, a tennis court, a golf course, and other resort amenities.

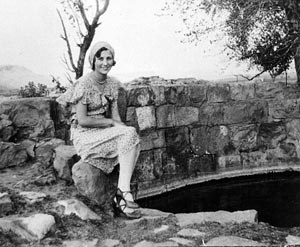

While his appearances with the actress Miss Dixie Starr and other promotional events were documented by the paper, of most interest to us here are the references for his plans for a swimming pool. In an article dated April 26, 1929, the scope was fairly modest: “There are two splendid groves of big cottonwood trees on the square mile. There is a spring that many a business eye has looked at with a view of making a splendid bathing pool.” Two months later (28 June, 1929), the undertaking had grown: “...a big cement swimming tank is to be placed among the fine grove of cottonwood trees, where a spring flows perpetually.” The tank was to vary from 18 inches to 10 feet in depth. A year later, the planned pool was going to be 18 inches to 14 feet deep, continuously renewed by not one but two springs, and would have bathhouses, according to an article dated 14 April, 1930.

While, ultimately, his plans for the fort never materialized in the manner Jack Hoxie planned, the swimming pool is mentioned in every article in which his plans are described and it seems likely that cleaning out the spring would have been an important first step towards the swimming pool and would have proved the viability of the pool (and, by extension, the rest of his enterprise) to potential investors.

Hoxie’s vision was never to come to fruition, however, and his plans fell apart in 1931. Little was done to maintain the fort and the buildings continued to deteriorate. There was interest in the property on the part of a local preservation group, but the asking price of the land was judged to be too high. In 1945, it was sold to Mack H. Sproul, who then sold 454 acres to David A. Simmons in 1946. Simmons wanted to use the site as a historic attraction and to provide vacation homes. It is known that he filled abandoned wells, and while there are no specific records describing his activities at the spring, a photograph he took in the 1940s shows the spring enclosure with a reconstructed wall and a functioning irrigation ditch.

After Simmons’ death in 1951, a group of local residents organized the Fort Davis Historical Society, but vandalism increased until the NPS acquired the property in 1961. It is unknown whether the members of the historical society attempted any maintenance on the spring enclosure, but cracks visible in a photograph taken in 1960 suggest that little maintenance was done. NPS preservation work appears to have begun in 1985, with work done in 1990, 1995, and 2002, before the most recent efforts in 2010.

Photo courtesy of Emily J. Brown.

Archeological Research at the Spring Enclosure

Archeological work began with documentation of the above ground masonry with a full-sized, scaled drawing of the individual stones and extensive photography, followed by comparison of the individual stones to those visible in historic photographs. It quickly became clear that the western section of the wall matched the historic photographs. This immediately eliminated the possibility that the entire spring enclosure was a reconstruction and that it had been built several feet offset from its original location. But another surprise awaited us as we removed the earth filling the inside of the spring enclosure so that the masonry could be better repaired.

The water table in this part of Texas has been falling and the spring stopped flowing several years ago; we were able to dig down into the spring enclosure without encountering ground water. Although we did not dig down to the very bottom of the masonry wall enclosing the spring, we did reveal two separate episodes of construction. Below the wall that extends above the ground surface today was an older enclosure made from much smaller, generally unshaped stones. There was an outlet on the north side, and the top of the stones was capped with a thin layer of concrete.

Photo courtesy of Emily J. Brown.

The stonework that was added to this was made of much larger, shaped stone blocks laid in a mortar heavy in lime. It appears that this later construction was built around and above the older one, completely enclosing and significantly enlarging the overall structure. There is an outlet in the southeast side, complete with a stone slab paving the bottom of it, which allowed the water to flow swiftly out at a steep angle.

In addition to exposing the different layers of architecture, the excavations recovered artifacts, including fragments of broken bottles, various types of nails (historic and modern), fragments of wire, and so forth. Analysis of the artifacts made it very clear that the earth in an around the spring enclosure had seen a great deal of disturbance over the years. The discovery of a modern penny from the year 2000 in a layer below one containing historic square nails was unexpected and would not have occurred if the layers in the spring had simply built up over time and remained intact. The mixture of artifacts of different ages throughout the fill suggested that at least the upper levels of the deposits in the interior of the spring enclosure were purposefully added at a later date and did not just develop over time. One possibility is that the fill was added during the early preservation efforts of the NPS in an attempt to make the deep spring enclosure safer for visitors.

If we look at the changes evident in the later additions to the original spring enclosure, they follow the Post Surgeon’s recommendations exactly. The new spring enclosure essentially encased the other in a large, impermeable wall. The lime-based mortar would have sealed it better, the height certainly would have restricted access by animals and even people, and the outlet was high in the wall and steep so that water could not flow back in. In this case, the archeological record verified the evidence in the historical records and provided the details on the construction that the historical records were lacking. The problems of obtaining water in sufficient quality and quantity was a reoccurring theme over the course of occupation of the fort. The story of the spring enclosure provides a window into one aspect of daily life at the fort and highlights the importance the army placed on a clean, reliable source of water in the challenging desert environment of western Texas.

By Emily J. Brown, Ph.D., R.P.A., Aspen CRM Solutions