Last updated: February 7, 2018

Article

History of the Shakers

Background

The Protestant Reformation and technological advances led to new Christian sects outside of the Catholic Church and mainstream Protestant denominations into the 17th and 18th centuries. The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, commonly known as the Shakers, was a Protestant sect founded in England in 1747. The French Camisards and the Quakers, two Protestant denominations, both contributed to the formation of Shaker beliefs.

The French Camisards originated in southern France during the 17th century. They regarded some of their leaders as Prophets, believing that they heard the word of God. Heavily persecuted by French authorities, they fought the armies of King Louis XIV from 1702 to 1706. After losing, some Camisards fled to England to continue their religious practices. While in England, their preachers heavily influenced a group of Quakers in Manchester.

The Quakers, or Society of Friends, were founded in England in 1652 by George Fox. Early Quakers taught that direct knowledge of Christ was possible to the individual - without need from a Church, priest or book. No official creed exists. Their belief that God exists in all people caused many to be sensitive to injustice and practice pacifism.

The name “Quaker” was derived from their process of worship, where their violent tremblings and quakings predominated. This form of worship changed in the 1740s, though it was retained by one group in Manchester, England. The “Shaking Quakers,” or Shakers, split from mainstream Quakerism in 1747 after being heavily influenced by Camisard preaching. The Shakers developed along their own lines, forming into a society with Jane and James Wardley as their leaders. Ann Lee, the founder and later leader of the American Shakers, and her parents were members of this society.

Ann Lee was born the daughter of a blacksmith in Manchester in 1736. She worked in a cotton factory, and in 1762 she married blacksmith Abraham Standerin. They had four children, all of whom died in childhood. Ann joined the Shakers in 1758, and 12 years later had "a special manifestation of Divine light." After this experience she became the leader of the Shakers. In 1774 she received a revelation directing her to establish a Shaker Church in America. Ann Lee, her husband, and seven members set sail for America on May 10, 1774. By late 1776 she and some followers were located northwest of Albany, New York, by which point she and her husband had separated. She gathered followers in New York until her death in 1784.

Shaker Beliefs

The Shakers practiced communal living, where all property was shared. They didn’t believe in procreation, and therefore had to adopt children and recruit converts into their community. For those that were adopted, they were given a choice to either stay within the community or leave when they turned 21.

Like the Quakers, the Shakers were pacifists who had advanced notions of gender and racial equality. The Shakers believed in opportunities for intellectual and artistic development within the Society. Simplicity in dress, speech, and manner were encouraged, as was living in rural colonies away from the corrupting influences of the cities. Like other Utopian societies founded in the18th and19th centuries, the Shakers believed it was possible to form a more perfect society upon earth.

Eventually there were 19 Shaker communities in the Northeast, Ohio, and Kentucky. They referred to those who lived outside their communities as people from "the World." They allowed contact with outsiders. Many outsiders, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, observed their religious practices. Communities were agriculturally based, and men and women lived, and mostly worked, apart.

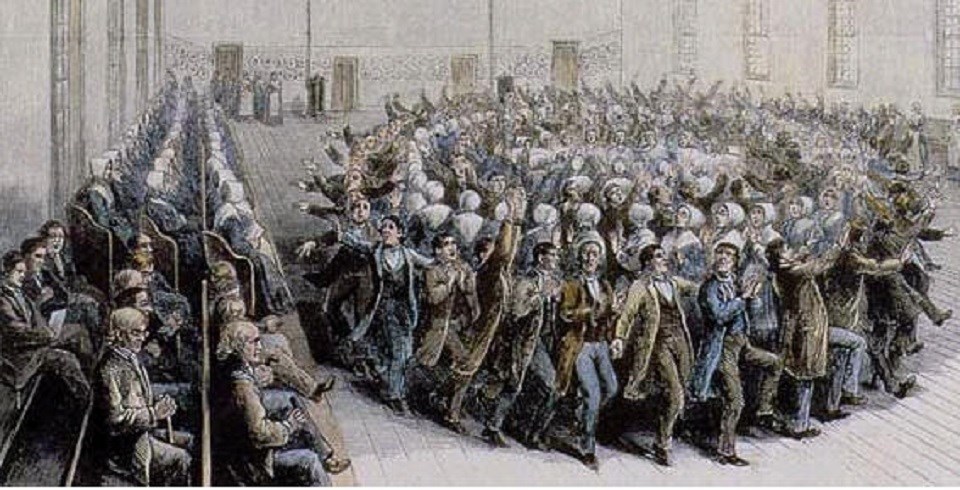

The community meeting-house was the center of Shaker worship services on Sunday. Spontaneous dancing was part of Shaker worship until the early 1800s, when it was replaced by choreographed dancing. Spontaneous dancing returned around the 1840s, but by the end of the 19th century dancing ceased during worship. Services consisted of singing hymns, testimonials, a short homily, and silence.

Sources:

- The Shaker Experience in America by Stephen J. Stein

- The American Soul Rediscovering the Wisdom of the Founders by Jacob Needleman

- Shakers Compendium of the origin, History, principles, Rules and Regulations, Government, and Doctrines of the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing with Biographies of Ann Lee, William Lee, Jas. Whittaker, J. Hocknell, J. meacham, and Lucy Wright by F.W. Evans

- Principles and Beliefs by the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village

- The Shaker Legacy Perspectives on an Enduring Furniture Style by Christian BecksvoortThe Architecture of the Shakers by Julie Nicoletta