Last updated: August 27, 2019

Article

History of Hidatsa: Pre-1845

Three Tribes Museum

Early Villages

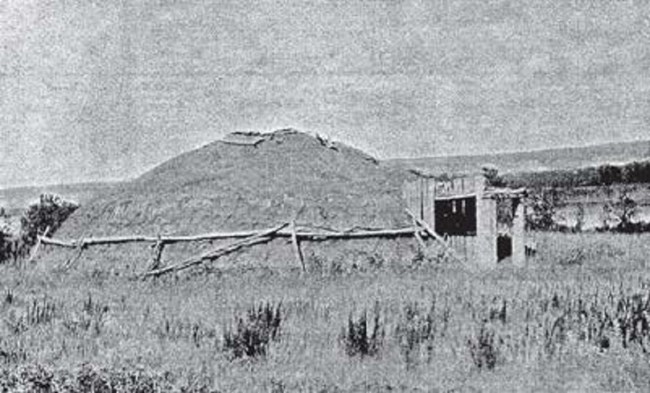

Located in the west-central part of North Dakota, the small town of Stanton is often visited by local farmers and ranchers, and by families or individuals who happen to be in the area. Three hundred years ago and possibly longer, a thriving earth lodge community of Hidatsa people engaged in trade with visitors to their villages. People came for the garden produce, clothing, moccasins, flint, tools, furs, buffalo hides, and other items the Hidatsa either produced or obtained through trade. Visitors were given food and drink, gifts were often exchanged, and then everyone brought out the items they wished to trade. Some of the items were saved by the Hidatsa for use in trade with other peoples.

Eventually, the Europeans entered the trade network that already existed with Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara in the plains region.

Adapted from Map 1 in Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains, University of Oklahoma Press, 1985

Three Tribes Museum

NPS Photo

Early Explorers

Following La Verendrye, other well known explorers documented their time spent with the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara including Meriwether Lewis and William Clark; the artist George Catlin; and Prince Maximilian of Wied who was accompanied by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer. All provided valuable information of the Knife River Indians through artifact collections, letters, notes, journals, sketches, and paintings. Catlin‘s work contextualizes Mandan life for us with sweeping villagescapes of activity around earth lodges, horse and rider scenes, and daring buffalo hunts. Bodmer’s finely detailed and colored portraiture of the three tribes provides in-depth knowledge of the various garments and accessories worn. We see the elaborate hairstyles of the men, the intricate porcupine quillwork and beadwork of the women, the use of feathers and fur in the headdresses, and the wolf tails trailing the moccasins. Together the two artists provide extraordinary visuals contributing to an enhanced understanding of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara in the early 1800’s.Sacagawea

When Lewis and Clark visited the area of the three tribes in 1804, a young Indian woman called Sacagawea (Tsa-caw-guh-wee-yuh [Bird Woman in Hidatsa]) was residing among the Hidatsa at the Knife River Villages with her fur trader husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, a Frenchman. Because Sacagawea had an understanding of the Shoshone language and was familiar with part of the route Lewis and Clark intended to take on their way to the Pacific Ocean, she was asked to accompany her husband, who was to serve as a guide on the trip. It was crucial for the expedition to communicate with the Shoshone in order to obtain horses for the westward journey. Sacagawea, around 17 at the time, made the trek transporting her infant son, Jean Baptiste, affectionately called “Pomp.” She proved to be of invaluable service to the Lewis and Clark expedition by retrieving research documents, medicine, instruments, books and other necessities when the boat nearly capsized. At times she also helped make crucial decisions like which route to take through the mountains. Her familiarity with the various uses of the flora and fauna had to be appreciated by Lewis and Clark in that they were documenting plants and animals as part of the expedition’s objectives.There is some debate as to what happened to Sacagawea after her return from traveling with the Corps of Discovery. She is reported to have died of “putrid fever” December 20, 1812 at the age of 25 at Fort Manuel Lisa Trading Post. One version, in the Hidatsa oral history indicates Sacagawea died much later from a gunshot wound in 1869 when the wagon in which she had been traveling with family members was attacked. According to the story told by Bulls Eye (Sacagawea’s grandson), his grandmother was 82 when she died from her wound after reaching a trading post near Glasgow, Montana. It is not known for sure where she is buried. Hidatsa oral history indicates she was buried in the Montana area. Most of what is known about Sacagawea is based on oral history.

Oral History

Before Europeans arrived among the villagers and began writing about them, the three tribes passed their history along through oral recitations. (Family and friends gathered to hear the elders tell stories in the evenings.) Stories were considered valuable teaching tools for young and old. Children were told stories with morals to encourage or discourage certain behaviors. The basis of many of the stories related to the concept of respect: respect for all things—animate and inanimate—was a basic tenet by which the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara lived. Outside of the storytelling environment, an individual could not hear or relate certain tribal stories without having paid for the right to the story. Personal stories belonged to an individual; clan and tribal stories belonged to a group of people. The stories often aided the people in understanding the world around them. Children thus learned much of their tribal history and societal values through stories.Education and Societies

Mandan and Hidatsa also educated children, youth, and adults through the use of societies. A young boy entered a society with children his own age and learned basic skills of hunting, fishing, warfare, horsemanship, and social responsibilities. When he became a teenager, he entered a society for teens to continue his education. He received more indepth instruction on his skills, learning the songs, stories and ceremonies related to each. When he became a man, he entered a society that helped him to become a leader, a healer, or some sort of provider within the community. Upon entering old age, a man could join different societies that were ceremonially responsible for the health and welfare of the people. The Black Mouth Society was an important men’s society. They kept order in the village. They ensured that the village was quiet at night so people could sleep undisturbed. They made sure that people kept the outside of their lodges clean and free of litter so that people could walk safely around the village. A Black Mouth painted his mouth and chin area black and forehead red so people could recognize him as he went around maintaining order.Societies also existed for young girls, teens, women, and elderly women. Young girls prepared for their roles as mothers through taking care of the dolls and the very small tipis made for their recreation. At the appropriate time, they entered societies where they were taught how to scrape a hide, sew tipis, clothing, and moccasins, build an earthlodge, do beadwork and quillwork, prepare foods, deliver babies, and engage in ceremonies. Women kept the inside and outside grounds of their lodges clean with brooms they learned to make of buck brush. The most important society was an elderly women’s group: the White Buffalo Cow Society called the buffalo to the village when the hunting parties were unsuccessful.

The societies were not free at any age. One was sponsored by his family or a group of people interested in seeing the person advance, like the clan for instance. The sponsors prepared feasts for the society members. Gifts such as buffalo robes, moccasins, animal skins, tipis, tools, and foodstuff were presented to the society members in payment for honoring the child/ person with entrance into the society. Those whose families could not afford to sponsor them within a society were taught much the same skills within their earth lodge family but without all the social connections.

Children were also taught to observe their surroundings. There were lessons to be learned by watching the animals, the plants, the world above. The Mandan children each year observed the O-kee-pa ceremony. For four days a dramatization of events related to the origins of the Mandan was conducted with audience participation. Dancers suffered for the betterment of the people by having their skin pierced. The annual reenactment reinforced learning of the Mandan origins among tribal members.

Three Tribes Museum