White Sands National Monument has been visited by human groups intermittently over the past 11,000 years. Due to the physical properties of gypsum, remnants of some of those occupations are preserved in a unique form.

Allison Harvey / NPS

These archaeological sites do not occur outside of the gypsum dune field and are likely not found anywhere else in North America, or possibly the world. These sites are known as “hearth mounds” and contain the remains of prehistoric campfires or roasting pits, known as hearth or thermal features.

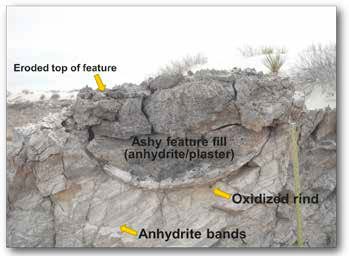

These archaeological sites formed when fires were built in the dunes; the heat from those fires converted the gypsum sand to anhydrite or hemihydrate (like Plaster of Paris). When the hearth features are exposed to moisture, the anhydrite material forms a hardened crust on the surface of the dune, preserving dateable charcoal, bone, pollen, and other cultural material. The portion of the dune encapsulated by this hardened crust erodes slower than the soft gypsum sand and remains intact as the dune migrates. Hearth mound sites vary in height and in the number of thermal features they contain. Thermal features are typically located on top of the mound, and when other cultural materials are present, they are usually concentrated at its base.

The challenging nature of the monument’s terrain makes pedestrian survey difficult and because of this only 5% of the property has been intensively surveyed for cultural resources. However, the erosional processes which occur at these sites result in a unique “footprint,” which is identifiable using remote sensing techniques. Recent remote sensing surveys conducted at the monument have revealed the presence of possibly thousands of potential archaeological sites throughout the dunes.

|

Objectives Objective 1 - Use remotely sensed imagery and photo interpretative techniques to develop a map of potential hearth sites. Objective 2 - Conduct field reconnaissance/ground-truth surveys to evaluate the precision and accuracy of the remote sensing data. Objective 3 - Document and date a sample of “hearth mound” sites. |

Methods

Using digital aerial orthophotography from 2003, 2005, and 2009 as the base, Natural Heritage New Mexico (NHNM) applied standard aerial photo interpretation techniques in a geographic information system (GIS) to identify potential hearth sites. Preliminary field validation was completed to evaluate the potential archaeological sites identified and adjust criteria to improve the accuracy of interpretive techniques. Following the final remote sensing survey, the Office of Contract Archaeology (OCA) at the University of New Mexico conducted ground-truth surveys to assess the accuracy of the remote sensing survey in identifying hearth sites. A total of 124 suspected hearth sites were examined during the ground-truth surveys. Locations that were positive for archaeological sites were documented and sampled for radiocarbon dating (14C), lithic, ceramic, and plant analyses.

Results and Findings

The photo interpretive survey yielded a total of 882 potential site locations within the monument’s boundary; of which 439 are located within the parabolic dunes. The results indicate that these archaeological sites are more numerous and widespread then initially conceived. Out of the 124 point locations visited during the ground-truth survey, only 15 locations were not hearth mounds but natural blowouts, burrows, or clearings. In total, 109 of the locations were verified as potential hearth mound sites, with hundreds of additional sites found during the process. Seventy of these locations contained hardened gray stained sediments, but did not contain visible charcoal or other cultural materials and therefore could not be confirmed with certainty as positive sites. In total, 39 locations contained cultural artifacts or features with visible charcoal and were recorded as archaeological sites.

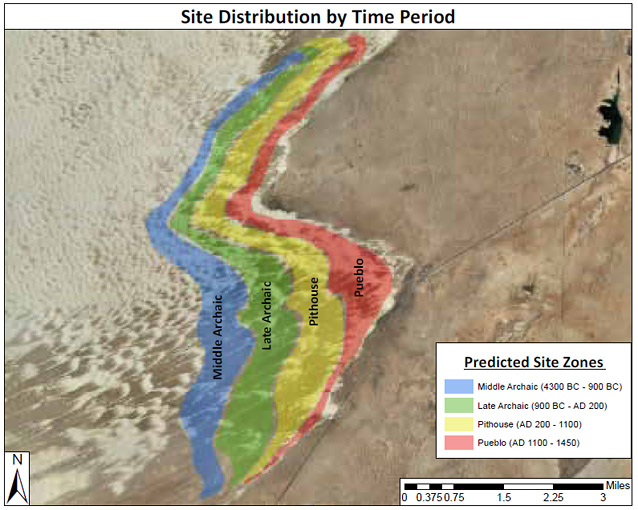

In an attempt to gain a better understanding of land-use patterns, twenty-six radiocarbon dates obtained during this study were combined with nine radiocarbon dates acquired during a previous study. The dates indicate that the parabolic dune field has been intermittently occupied from at least 2500 BC through AD 1300. When all of the collected dates were plotted on a map (in ArcGIS), an interesting spatial and temporal pattern emerged. The oldest sites are located in the westernmost part of the study area and the dates are progressively younger in the east along the leading edge of the dune field.

Discussion

The site distribution pattern exposed by the radiocarbon dates reveal period-sensitive site zones, which can be used as a predictive model for dating sites and may also help determine where the leading edge of the dune field was located over time. This pattern suggests that prehistoric groups were camping along the leading edge of the dune field where they would have access to the freshest water and food resources. Consequently, as the dunes advanced over time, settlement locations shifted northeast following the natural progression of the dunes.

There are potentially thousands of archaeological sites located throughout the monument. We have only scratched the surface in recording and understanding the unique cultural resources found within our boundaries. Ground survey is ongoing to continue verification of remotely sensed data and to record and describe previously unknown sites. Further studies are needed to obtain additional radiocarbon dates to evaluate the hypothesis that site locations moved with the leading edge of the dune field and that a site’s location may predict its age.

For more information, contact:

Allison Harvey, allison_s_harvey@nps.gov

White Sands National Monument

Prepared in collaboration with the National Park Service, 2012.

Last updated: April 27, 2022