Last updated: April 14, 2020

Article

All Hands On Deck: starry salute to a Navy veteran

NPS / Julie West

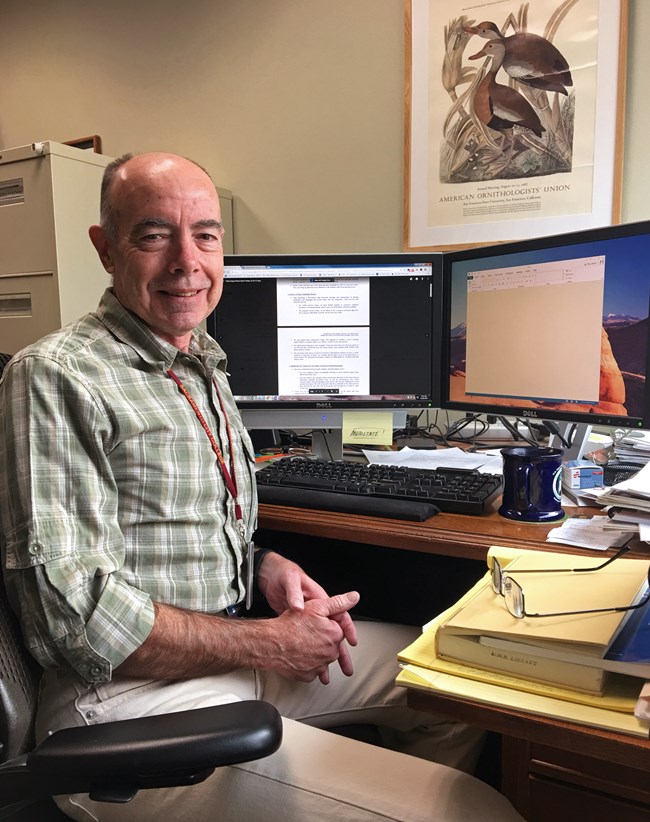

On long voyages far from home, National Park Service employee and Navy veteran Jim Haas said he often looked to the stars for comfort and inspiration.

“Out on the open ocean at night you could step out on the bridge wing and look up, and on a clear night the sky was like nothing you could ever see on land. It was so intense it was almost magical.”

Haas chatted with communications specialist Julie West of the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division about his years of service in the Navy on board ships near and far from home under starry skies.

The National Park Service is proud to commemorate the service of America’s veterans, and shine a light on those, like Haas, who are NPS employees. Haas is currently Chief of the Resource Protection Branch of the Environmental Quality Division in the Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate in Fort Collins, Colorado. From standing night watch to weathering storms, the Navy gave Haas a gamut of adventures and skills for navigating life both on and off duty.

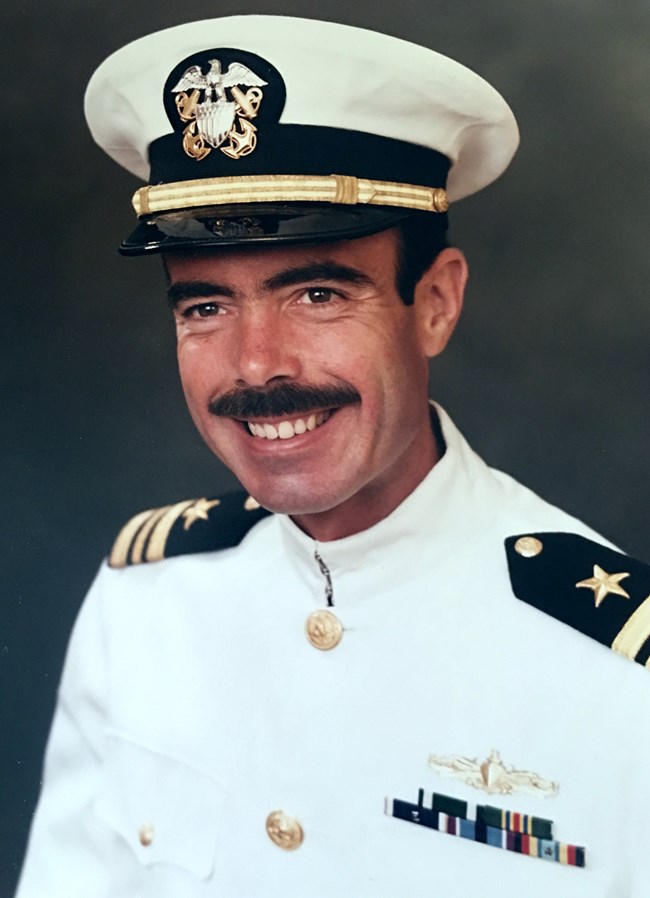

Photo courtesy Jim Haas

When did you serve in the Navy?

I went in right out of college. I was commissioned at the end of 1974. I was on active duty for almost 11 years after that. I got out in 1985 to go to graduate school at San Francisco State University.

Did you have an idea of what it would be like to be in the Navy?

My dad was a career Navy officer and veteran of WWII and Korea, and most of the officers he served with when I was a kid were Korean War and WWII veterans. I had an idea based on seeing my father interacting with his peers, and occasionally visiting a ship that he was assigned to. There were a lot of personal, first-hand stories of service in the war. I also grew up watching World War II movies with my family.

What was your title and first assignment?

My first assignment was to a minesweeper out of San Diego. They were unique at the time because in order to sweep influence mines—mines set off by the magnetic signature of a ship—the ships had to be non-magnetic themselves. So the hulls were made out of wood instead of steel, and the engines were made with non-magnetic alloy metals. It was really interesting. We had maintenance problems that other ships didn’t have because they were made out of steel or aluminum. It was a good introduction to the Navy and learning seamanship and ship handling and all those kinds of things. I was the First Lieutenant on the ship, which is the senior deck officer.

Was there a responsibility or duty during your service that makes you most proud?

Yes. I was a good watch stander. I was a good Officer of the Deck. You have to get qualified to stand watch on board the ship, because the captain can’t be awake 24/7, and the Officer of the Deck has the responsibility and authority of the captain. And you have not only yourself but the entire watch team: signalmen, radiomen, the deck watch-standers like the helmsmen, the lee helmsmen, the lookouts, the Boatswain’s Mate of the Watch, and then all the engineers. That was something that I was proud of, and I took the job very seriously. You’re scanning the horizon looking for unusual signs, radar from other ships, and anything that could be a potential threat. That usually means other ships. In most of the coastal areas there are a lot of fishing boats and merchant traffic that you don’t want to run into like what happened in the last year. The Navy had two serious collisions overseas, and that’s something you never want to happen.

You must have seen some incredible night skies as a watchman.

Seeing the night sky was one of my favorite parts about standing night watches. One of the objectives of the ship was to make itself as invisible as possible. Usually the only lights we’d have on would be the lights we were required by law to have called the running lights. So there was a green one and a red one up front, and mast head lights and a stern light that were white. On the bridge we would use red lights at night to protect our night vision instead of white lights, so when you were out in the open ocean at night you could step out on the bridge wing and look up, and on a clear night the sky was like nothing you could ever see on land. It was so intense it was almost magical. Getting ready for the watch I would go up and stand for a while and stare at the sky.

Did you know any of the constellations?

I learned some of them, mainly out of curiosity. We did use stars for celestial navigation, and so we’d have to identify specific stars sometimes and use a sextant to get the angles. And then you’d go through this really complicated set of calculations to figure out how that translates to your position on the surface. That was something that we did every night.

And the Navy has re-introduced celestial wayfinding recently.

Yeah, they should. When all that electronic stuff breaks down, you still need to figure out where you are. It’s an important skill.

What’s the most remote location where you experienced the stars?

It would probably be the Mid-Pacific, because there isn’t a whole lot between Hawaii and the east coast of Asia. We were on a frigate doing what was called a SOUTHPAC cruise – Southern Pacific. Instead of going straight from Hawaii to the Philippines, we went south across the equator to American Samoa, Fiji, New Caledonia and Australia. Once you get below the equator, you start to see the Southern Cross and other constellations that aren’t always visible from the Northern Hemisphere. I felt like it was a rare opportunity, and I’m very grateful for it. And operating in the Sea of Japan in late winter or early spring I would also see the aurora borealis. And there were always shooting stars and meteor showers. It was a very neat experience.

You were a long way from home in the Navy. Was the night sky a comfort?

Yeah, I’d think, “I’m looking at these stars, and someone that I know and love is looking at them from a different location.”

Did you see any other curious phenomena at sea?

When the sky is really clear and you have a good horizon, there’s a phenomenon called the green flash that you see as the sun is going down. It has to do with the way light refracts through the atmosphere. As the sun slips below the horizon, if it’s really clear you can see a green flash. It lasts for less than a second and it’s gone. So we’d always look for that at sunset. Usually there’s so much haze along the Pacific coast that you don’t see it well. You need both a clear atmosphere and horizon. Of course, we were able to observe a lot of ocean marine life. A lot of the time dolphins or porpoises would ride the bow wave and surf alongside the ship for a while. That was always cool. And occasionally you’d see a shark or a sea turtle. When you were within range of the coast there were always birds. There were fewer birds further out, but occasionally you’d see an albatross. I think my education—my background in natural resources from college—was probably a factor in the degree of my appreciation for these experiences, and made me more attuned to the natural phenomena going on around me.

What about storms?

Each of the ships I deployed on managed to get sucked into at least one typhoon. That was always nerve-wracking, not that the ships weren’t stable, but it added an element of complexity when you’re trying to navigate and keep your balance at the same time because the ship is rocking back and forth. One time we got into a storm where the swells were higher than the bridge wing of the ship. We were taking up to 45 degree rolls. Because it was a small ship, it was intense. Just standing, you had to be able to concentrate. There was a place where you could stand next to the radar repeater and compass, and you could hang on to that and brace yourself so you weren’t constantly rearranging your footing to stay upright. A lot of the guys got really sick.

Another one of my favorite storm stories was when we were anchored in Hong Kong Bay. I was on active duty on an ammo ship. Because we carried ammunition, we couldn’t go into port. We had to anchor out, because if there had been an accident, we had a blast radius of about 10 city blocks, so they didn’t want any tragedies to happen to anyone other than us. We used small boats to get back and forth to the main land. While we were anchored, I spent the night in Hong Kong. I got back to the ship about mid-morning, and the command duty officer was like, “Jim, Jim … CTF73 (Commander Task Force 73) says there’s a typhoon coming, and they want us to get underway as soon as possible, but I don’t know where the captain and the executive officer are. I don’t know what to do.” The chief engineer happened to be there in the wardroom, and I looked at him and said, “Engineer, when can you have the main engine on line?” And he said, “Well, if I start now, 1600.” And so I told the command duty officer, “Tell CTF73 we’ll be underway at 1600, and we’ll work with whoever we have back on board by then.” So we started doing that. The engineer came up to me after we had that discussion. He was senior to me, and if we’d had to get underway without the captain and the executive officer, technically he would have been expected to take command. He said, “Jim, I know I’m senior to you, but if we have to get this ship underway without the captain I want you to be in command.”

What happened, where was the Captain?

The Captain and XO made it back. This was before Hong Kong was turned back over to the Chinese, so the British Navy still had a presence there, and we had a liaison officer, and they were very adept at rounding up stray crew people when a ship had an emergency or something. So they got hold of the captain and the XO and made sure they knew they had to get back to the ship right away.

What was your title at the end of your 11-year service, and what were your responsibilities?

I made the rank of lieutenant commander. In my last assignment I was the Operations Officer on board an ammunition ship. I was responsible for scheduling, managing the navigator, the operations specialists, and the Combat Information Center. The radiomen and the signalmen were all my guys. Because we were an ammunition ship, we did periodic underway replenishments with other ships to transfer them food and fuel and ammunition. That was a complex process, so we focused on logistics and training to make sure we were prepared and did things well.

What aspects of your work with the Navy have shaped your character and performance with the NPS?

One of them is that I am a lot better organized. I attribute that to being in the Service. The self-discipline and work habits that I developed to survive in the Navy I’ve always been able to apply to my outside life.

Julie West, Communications Specialist, Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division