Last updated: May 4, 2022

Article

Golf Course as Classroom: University of Pennsylvania at East Potomac Park

NPS/Shannon Garrison

Starting in the spring of 2016, early morning golfers and lunch break players might have seen an unusual sight: four people in golf carts with cameras and notebooks instead of clubs and bags.

This team from the University of Pennsylvania School of Design’s program in historic preservation was studying the three National Park Service golf courses to write Cultural Landscape Inventories for the National Capital Region’s Cultural Landscapes Program. They logged hours in the field, in the archives, and in the classroom to understand the unique challenges of documenting and preserving the ever-changing golf course landscape.

Library of Congress

Why Preserve a Golf Course?

East Potomac Park Golf Course opened in 1920, during the “Golden Age of Golf,” at a time when urban reformers and park planners believed that public space for sports and recreation was vital to the health of city dwellers. Golf exploded in popularity in the United States around 1900, and many cities began to build public courses.

The East Potomac Park Golf Course was one of the first of eight public courses built in Washington, D.C. and is one of three remaining today.

Golf champion and course architect Walter J. Travis designed East Potomac as a traditional links style course. “Links” is a term derived from ancient Scotland to describe a rough, grassy area along the coast with sand dunes and few trees. East Potomac Park, a flat peninsula along the Potomac River, was a natural match.

NPS Photo

Travis designed a reversible 18-hole course, which is now one way and known as the Blue Course. He instructed the builders to follow and enhance the natural terrain with dozens of sand pits and other hazards. The course’s topography and vegetation, its clubhouse, and its views of the Washington Monument and Washington, DC skyline are all part of its unique character.

Tim Evanson (Creative Commons license on Flickr)

When it opened, it was so popular that golf architect William Flynn was hired to design another nine-hole course, today’s White Course. By 1931, the course boasted a third nine holes (the Red Course), a putting green, and a miniature golf course.

East Potomac is also notable for its role in African American civil rights history in Washington, DC. In the early years of the course, African Americans were only allowed to play on two half days each week. Segregated courses built for black golfers elsewhere in the city in the 1920s and 1930s were small and poorly maintained.

In 1941, three African American golfers - Asa Williams, George Williams, and Cecil R. Shamwell - protested their lack of access to the city’s best courses by walking onto East Potomac Park Golf Course and playing a full 18-hole round. They were followed by the U.S. Park Police to keep violence from other golfers at bay. The visibility of this protest forced the National Park Service to respond immediately at the highest levels by integrating all of Washington’s public golf courses, contributing to integration in both the National Park Service and Washington, DC during the 1940s and 1950s.

Historic Preservation Challenges & Solutions

While researching the history of the landscape, the University of Pennsylvania team had to ask: Is today’s East Potomac Park the same landscape Walter J. Travis designed, where three black golfers challenged federal policy?

NPS/Shannon Garrison

The University of Pennsylvania students and project managers grappled with the answer. Golf courses are complex landscapes with intentionally designed features, but changes are expected. For example, greens are redesigned and tee boxes are moved in order to give golfers more variety, cater to different skill sets, and conserve turf. Fairways (the stretches where golfers hit the balls) were lengthened as metal clubs replaced wood, allowing golfers to hit balls a greater distance. The researchers wondered whether they would have to prove that every hole, tee box, sand pit, or tree was in the exact same location as in 1920 to show how the course’s current condition reflects its historic landscape.

University of Pennsylvania Research Associates Shannon Garrison and Molly Lester managed the project with Principal Investigator Randall Mason, Chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation. Two students, Mikayla Raymond and Ty Richardson, joined this project as the “praxis” component of their graduate studies. The praxis requirement gives them an opportunity to apply their classroom education to solving hands-on problems in landscape preservation.

The team incorporated fieldwork, research, and discussions with golf historians, concessionaires, park managers, and landscape architects to develop a methodology for documenting large, complex landscapes. This is where the golf carts came in handy.

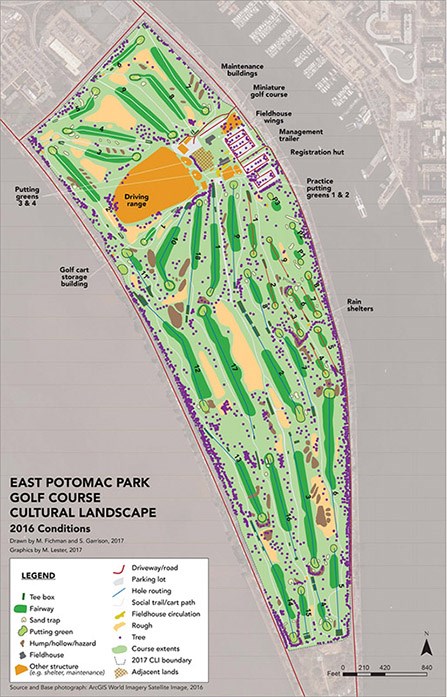

NPS map by M. Fichman, S. Garrison, and M. Lester

Over three site visits, they took photos of the landscape at each hole and documented the course’s vegetation; features like fairways, bunkers, and sand traps; roads and paths; structures; and views. They also used historic maps, photographs, and documents to understand the course’s evolution, creating a timeline and GIS maps of what it would have looked like in the past and present.

Ultimately, they found that the nature of a golf landscape is that it is designed to change. Some of the changes at East Potomac Park are significant: For instance, the once reversible courses became one-way, pathways were modified, fairways extended, and major aspects of Travis and Flynn’s designs have been altered. Other features hark back to the landscape’s origins. The players still take similar routes across the course, the original clubhouse remains the starting point for all games, and the course’s overall character and setting give it the feeling of a public course from the Golden Age of Golf.

The team’s Cultural Landscape Inventory will help the National Park Service preserve the past for players in the present. The students, Mikayla and Ty, both graduated with an MS in historic preservation in 2017, and both continue to work with the National Park Service. The project managers are planning their next joint project between the National Capital Region’s Cultural Landscape Inventory and the University of Pennsylvania’s historic preservation program.