Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

Lichen Inventory of Glacier Bay National Park

By Toby Spribille (Univ. of Montana), Alan Fryday (Michigan State Univ.), Måns Svensson (Swedish Univ. of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala), Tor Tonsberg (Univ. of Bergen, Norway), Sergio Perez-Ortega (Spanish Science Foundation, Madrid)

Is Glacier Bay significant for the diversity of lichens found here?

Dates:

September 2011– March 2014

Introduction

The importance of Southeast Alaska as a hotspot for lichens was recently underlined with the documentation of 766 species from Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park, making it the richest park in the national park system and the richest single local flora to date in North America. Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve may have an even more impressive lichen flora, considering that it is 250 times larger and contains greater geomorphological, geological and climatic diversity than Klondike Gold Rush.

The specific objectives of this inventory are to:

1) compile information on lichen specimens previously collected in Glacier Bay;

2) based on new field work, create a comprehensive list of lichen species collected or detected in the park;

3) complete a reference collection of voucher specimens and associated data for the herbaria of Glacier Bay and the University of Alaska, Fairbanks;

4) collect preliminary distribution and local rarity information and obtain GPS data for each lichen sampling site;

5) establish long-term climate change monitoring plots at selected sites;

6) develop educational materials for visitors and interpreters.

The utility of lichens as indicators of air quality has been recognized since the Industrial Revolution in England. Lichens are uniquely suited as bio-indicators, since they absorb water and nutrients directly from the atmosphere. Species differ in their sensitivity to pollution, so mapping the occurrence of different species can provide detailed information on air quality. This study is designed to augment studies in Glacier Bay intended to monitor the long-term environmental effects of cruise ship stack emissions.

Methods

Over two field seasons, the research team conducted surveys at 186 sites in the park and collected approximately 4900 specimens. In addition, historical Glacier Bay lichen material was located in several national herbaria. These include collections made during the Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899 and collections by W.S. Cooper and D.B. Lawrence. Material from these collections will be borrowed, inventoried and studied.

The next step is to complete identification of the collected material and map patterns of distribution. The emerging patterns will be an important baseline for developing hypotheses about species colonization and dispersal in post-glacial ecosystems. The work of describing new species has just begun. Each species must be compared against other members of its genus and family and DNA sequenced, a time-consuming process.

Findings

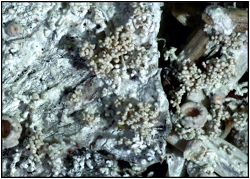

Before this survey, only 69 species of lichen were known from Glacier Bay. The current study has increased this tenfold: a total of 680 species have now been identified, including nearly 50 that appear to be new to science. Analyses are ongoing and the total number of species is expected to exceed 750. One new species is a crust with coralline structures that appear to serve as dispersal propagules. The authors are provisionally naming it Ochrolechia cooperi after W.S. Cooper. It is known from four sites in the southern part of Glacier Bay.

Lichen diversity is distributed across the entire region. However, two habitats stand out. Glacier Bay is home to what may be a unique phenomenon: parallel beach cobble ridges that are being actively uplifted by isostatic rebound. This unique combination creates a living cross-section of primary lichen succession from bare rocks to densely colonized cobbles and pebbles; dozens of species have been found in this habitat.

Another remarkable habitat stands in contrast to the young surfaces in Glacier Bay. The alpine ridges above the glaciers harbor a spectacularly rich flora with close to one third of all species found in Glacier Bay to date. Rare species of global significance are found in these areas, which are important sources for colonization of deglaciated surfaces.