Part of a series of articles titled African American Communities Along the C&O Canal.

Article

Gibson Grove (Cabin John), Maryland

Oral tradition maintains that the Gibsons migrated to DC during the war and then to Cabin John, where Robert Gibson worked as a farm laborer and Sarah Gibson earned a living as a seamstress. By 1880, the couple had purchased a four acre parcel on Seven Locks Road. In 1881, the Gibsons sold a quarter-acre lot from their land to John D.W. Moore (a White landholder and owner of a local quarry), who then negotiated its sale to the county’s school board the following year for the erection of a school for local Black children. Called Moore’s School colloquially, the log cabin was built in 1882 from timber harvested on the Gibson property. It was intended to double as a house of worship for the Black community on Seven Locks Road.

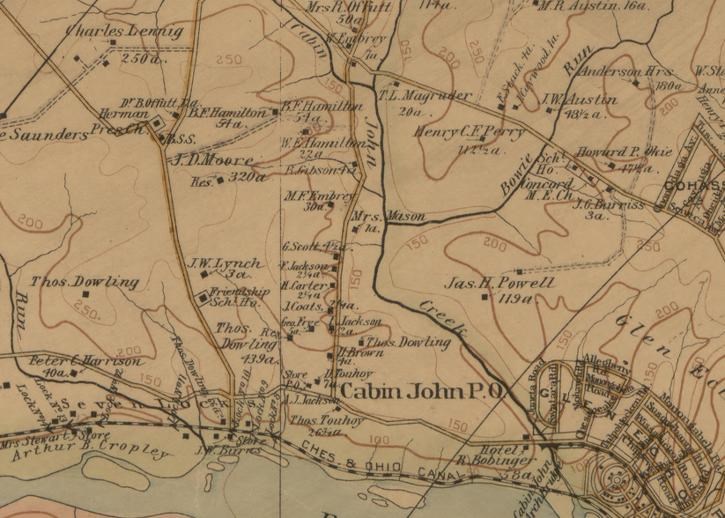

Excerpt of The Vicinity of Washington, D.C., 1894. Repository: Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

The Order of Moses

In 1885, the No. 10-Gibson Grove community established a fraternal organization, the “Ancient United Order of the Sons and Daughters, Brothers and Sisters of Moses, hereafter the Order of Moses.” In 1887, John D.W. Moore sold a one acre lot to Gibson Grove community members on which a two-story, wood-frame building was constructed and a cemetery established. The Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 was the first Order of Moses building erected in Montgomery County, although the fraternal organization had a history in DC stretching back to 1876. The Order of Moses proved to be the backbone of the Gibson Grove community. All its households were members, and its membership dues were pooled to cover burial costs and to care for sick community members.Gibson Grove Working Life

By 1900, Gibson Grove had grown to include 122 inhabitants divided among 18 African American households. In these households, nine men were farmers, seven were general laborers, six were quarrymen, five were railway workers, and three were hotel staff. Several women worked as domestic help in private homes or local hotels, and others took in laundry to supplement their incomes. Other Gibson Grove residents were employed by Clara Barton at her American Red Cross Headquarters in neighboring Glen Echo. This included Emma Jones, who served Clara Barton as both a nurse and housekeeper until Barton’s death in 1912. Emma Jones also was a midwife in the Gibson Grove community. Many Gibson Grove families practiced small-scale farming on their properties. For instance, Charles H. Brown’s 4.5-acre parcel was a "truck farm" from which he earned an income, selling fruits and vegetables at markets in Washington, DC.![Cabin John Hotel Ad [Resized] Newspaper Ad from 1896 for the Cabin John Hotel. The ad talks about the genial hosts, top quality cuisine, and spectacular views found at the hotel which can be reached by cable car or via Conduit Road.](/articles/images/Cabin-John-Hotel-Ad-Resized1.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false)

The Morning Times, Washington, D.C. 1896 Repository: Chronicling America, Library of Congress

According to a real estate atlas published in 1917, the Black landowners shown on Seven Locks Road were the same founding patriarchs and their descendants. With World War I came the increased development of Cabin John as a summer-cottage community for Washingtonians. Cabin John had been a resort area from the 1870s with the opening of the popular Cabin John Hotel, near the Cabin John Aqueduct Bridge, but the resort era waned with the closure of the hotel in 1925. Several Gibson Grove residents, such as Mariah Gray, had been employed by the hotel.

Despite setbacks in the local economy, the Gibson Grove community was intact at the onset of the Great Depression. The region’s economy was slightly buffered from the downturn by the presence of federal agencies and federal work programs, such as the two Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps that were established in neighboring Carderock from 1938 to 1942. These camps were segregated CCC bases for African American enrollees in the program. The young Black men (aged 18 to 25) who came to Carderock and Cabin John in the late 1930s and early 1940s labored to restore the first 24 miles of the C&O Canal for the National Park Service. This section of the canal was opened to the public in 1940 as a parkland.

Carver Road

From 1938 to 1939, the US Navy built the David Taylor Model Basin in neighboring Carderock. In the spring of 1939, the Navy constructed worker housing for laborers engaged in the basin’s construction. On Charles H. Brown’s 4.5-acre property on Seven Locks Road, the Navy built a residential development with 25 homes for Black contractors. Called Carver Road, the new homes were rented for a monthly payment of $28 and many were sold to the occupants within a few years. The Carver Road community brought a second wave of Black settlement into Cabin John that integrated with the extant Gibson Grove community.

Used with permission. Courtesy of Montgomery History.

Divided by the Beltway

The Gibson Grove community was effectively cut in half by the construction of the Capital Beltway (Interstate 495) at Cabin John in the 1960s. The Morningstar Tabernacle building with its cemetery as well as the original No. 10 residences and Carver Road community lay south of the interstate while the former Gibson property and the Gibson Grove A.M.E. Zion Church lay to the north. The Morningstar Tabernacle building survived the interstate construction only to be lost to arson later in the decade, and the original Cabin John School building was also lost. The Morningstar Tabernacle cemetery and the Gibson Grove A.M.E. Zion Church are the last remaining built institutions of the historical Gibson Grove African American community. Local preservation efforts are ongoing to bring awareness to these sites.Information in this article comes from the National Park Service Historic Resource Study: African American Communities Along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, by Heather McMahon. Produced by the National Park Service and WSP USA Inc., 2022.

Sources

- “Founders Day Celebration: Gibson Grove African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, 7700 Seven Locks Road, Cabin John, Maryland” [program], 17-18 June 1976 (accessed 17 November 2021, https://mchdr.montgomeryhistory.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12366/382/FoundersDay1976GibsonGroveAMEZChurch.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y).

- Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. The vicinity of Washington, D.C. Philadelphia: Griffith M. Hopkins, C.E, 1894. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/88693364/

- Alexandra Jones, Gibson Grove Gone But Not Forgotten: The Archaeology of an African American Church (Berkeley, CA: doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley. 2010).

- Clare Lise Kelly, Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland, 10th Anniversary Edition (Silver Spring, MD: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, 2011).

- Elizabeth Kytle, Time Was: A Cabin John Memory Book: Interviews with 18 Old-Timers (Cabin John, MD: Cabin John Citizens’ Association, 1976).

- Barbara Martin, “People of Cabin John” (Cabin John, MD: Village News, 1995). Repository: Montgomery History, Jane C. Sween Library, Rockville, MD.

- Judith Welles, Cabin John: Legends and Life of an Uncommon Place (Cabin John, MD: Cabin John Citizens Association, 2008).

- L. Paige Whitley, “The History of the Gibson Grove Community and the Gibson Grove AMEZ Church, Cabin John School and Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 Moses Hall and Cemetery” (Cabin John, MD: prepared for Friends of Moses Hall, January 2021).

Tags

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- national capital region

- national capital area

- ncr

- c&o canal

- maryland

- montgomery county

- washington d.c.

- district of columbia

- cabin john

- gibson grove

- history

- african american history

- black history

- civil rights

- reconstruction

- reconstruction era

- recreation

- outdoor recreation

- education

- clara barton

- american red cross

- the order of moses

- morningstar tabernacle

- emma jones

- cabin john hotel

- mariah m. gray

- civilian conservation corps

- ccc

- david taylor model basin

- carver road

- world war ii

- capital beltway

- interstate 495

- gibson grove a.m.e. zion church

Last updated: December 13, 2023