For the wounded near the front, their first recourse for care lay at the numerous aid stations scattered across the battlefield. Farmhouses, barns, and outbuildings provided places for the wounded to be gathered until they could be sent to the main hospital in the rear.

"The whole region of country between Boonsboro and Sharpsburg is one vast Hospital. Houses and Barns are filled with them, and nearly the whole population is engaged in waiting on and ministering to their wants." Hagerstown Herald-Mail September 24th, 1862

Aid Stations and Field Hospitals

NPS

The Stone House, a private home and tavern at the intersection of two major roads, became prominent as an aid station during not just one, but two major battles. During the First Battle of Manassas, Union battle lines swept past the house, leaving the dwelling to shelter wounded men brought inside amid the fighting. During Second Manassas, since the house lay more firmly in Union hands, Federal personnel were better able to give aid to the wounded, creating a more established field hospital. To mark the building's new purpose, Northern surgeons hung a red flag from a second floor window.

Despite the distinctive identifying flag, the Stone House did not escape hostile fire unscathed, underscoring the risks that wounded troops faced at forward aid stations. As Confederate forces mounted a massive counterattack on August 30th, a wounded Union soldier was attempting to reach the house for aid when an artillery shell hit the building, "knocking a hole that looked as big as a bushel basket" in the house's western face. The private continued rearward, determined to find a safer shelter. Scenes like this were common in the fear and confusion of a battle. Throughout the Maryland Campaign, many homes, stores, churches, schools, and barns served as aid stations.

Hospitals and Homes

Library of Congress

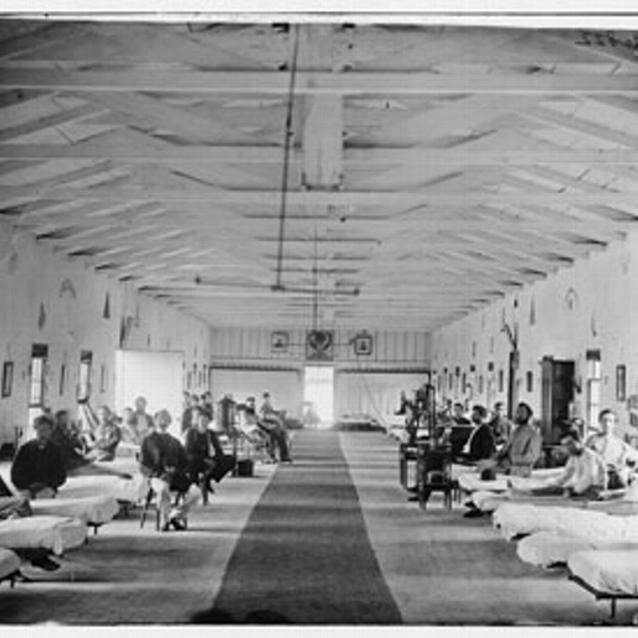

After the Maryland Campaign, Frederick was inundated with wounded soldiers, whose sheer numbers overwhelmed the capacity of the existing hospital on the Hessian Barracks grounds. Additional buildings were taken over for hospital purposes and organized into seven General Hospitals, under the care of seven separate sets of surgeons. A total of 27 buildings were used, mainly churches, schools, hotels and large meeting halls. In addition, two hospital camps were set up in tents on the outskirts of the city and many private homes housed wounded officers.

Many local citizens helped tend to the wounded soldiers on the battlefield, some arriving as early as the evening of the Battle of Antietam. They gave freely of their time, food, money, and compassion. The scale of the relief effort cannot be overstated. One pregnant woman in town had torn the family's clothing and bedding into strips for bandages, packed water and goose grease into containers, and headed out to assist the wounded with her young children in tow. When families returned home and found their houses and barns taken over for hospitals, they often helped care for the injured soldiers. Local women also volunteered at large field hospitals. They brought food and delicacies, bandaged wounds, helped write and deliver letters, and read to the soldiers to help lift their spirits.

All of the hospitals, with the exception of General Hospital #1 on the Hessian Barracks grounds, were closed by March of 1863 and the buildings returned to their former uses. However, it took much longer for the soldiers and civilians who witnessed such carnage, pain, and death to recover from the psychological wounds of war.

Part of a series of articles titled A Most Horrid Picture.

Previous: The Reason Medical Practices Changed

Last updated: August 14, 2017