Part of a series of articles titled The 15th and 19th Amendments go Underground: The Antislavery Movement and Voting Rights .

Article

“Liberty and Equality shall embrace each other:” Free African Americans Before the Civil War Who Made the 15th Amendment Possible

The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, the important constitutional amendment that guaranteed the right to vote to all men regardless of “race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

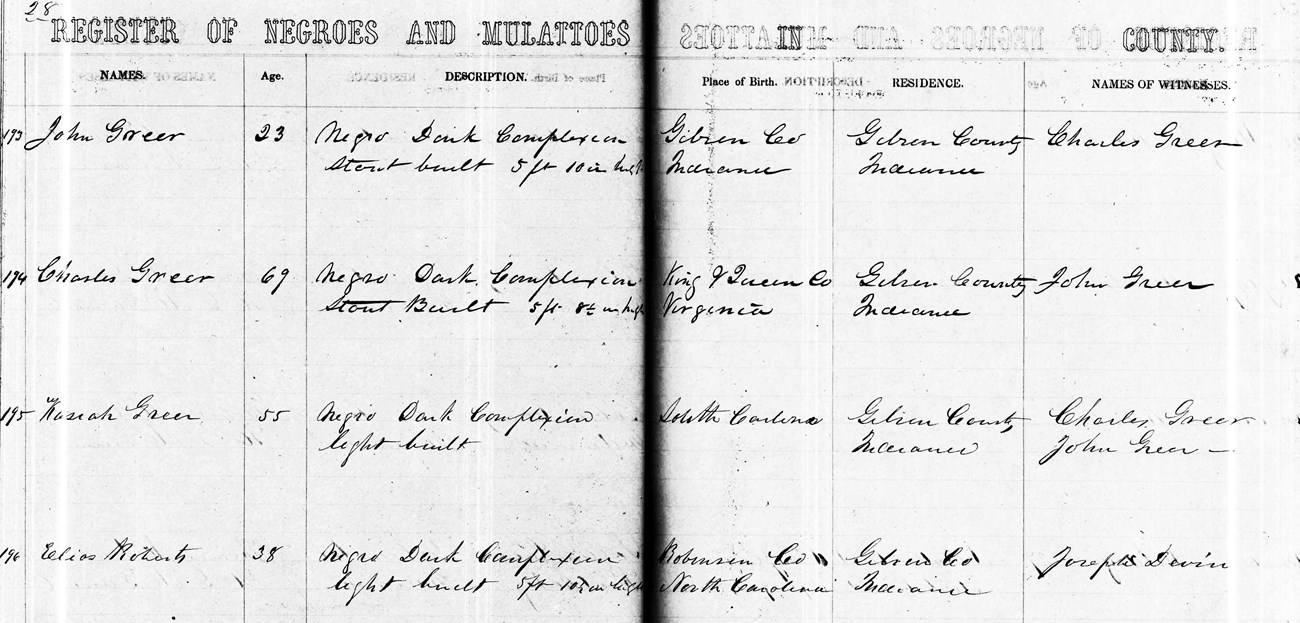

Charles Grier was dying. It was the spring of 1872, and he was almost ninety years old. Charles had been born in bondage in Virginia at the very end of the Revolutionary War. He had lived through the War of 1812 and the Civil War, finally seeing the end of slavery. But Charles Grier had seen his freedom come during a much earlier period in the nation’s history, when a fervor for freedom and equality were sweeping the new nation.

In 1813, Charles Grier arrived in the Indiana Territorial frontier, a region that was being violently torn apart by the War of 1812. He had been brought to the territory in order to be freed, and picked his new last name to honor the Rev. Grier -- the man who freed him. However, he was not the first African American settler in the territory. There had long been multi-racial Afro-French people who had lived and worked throughout that region, some enslaved. By the time Charles Grier arrived there were already enough free African Americans along the Wabash River for Governor William Henry Harrison to raise a Black regiment that fought in pivotal battles of the War of 1812. These early pioneers of African descent had come to this region drawn by the promises of the Northwest Territorial Ordinance of 1787. It stated that slavery would be banned and all men would have an equal right to vote.

Charles Grier hoped to purchase good land for a farm, but he arrived with nothing except his freedom. By 1815 he had worked hard to earn enough money to purchase his first piece of good frontier land from the Federal government. He had established himself by 1818 and was able to marry his beloved Keziah. She had also been born enslaved, and had been brought to Indiana from South Carolina. By 1818 she and Charles were working to grow their farm and their family, and worshipping in a racially integrated congregation led by the white Southern-born preacher, Elder Wasson.

Princeton Public Library - Wabash Valley Visions & Voices: A Digital Memory Project

Soon Charles and Keziah were helping further the cause of liberty as Underground Railroad operatives, continuing their work well into old age. This was risky considering getting caught could result in the loss of their own freedom.

The Griers, however, were just one of example of the many free African Americans in the Old Northwest Territory states working to further freedom for all. They lived scattered across Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. Before the outbreak of the Civil War they were farming their own land in the over 330 rural settlements that existed across those five states. Many had arrived in the region before there were cities, and some were instrumental in founding important cities like Chicago, Evansville, Columbus, Cincinnati, and Detroit, when those places were little more than frontier villages and forts. For these free African American pioneers, their work to end slavery and assist freedom seekers was combined with a determination to work for equal citizenship rights.

They had much to fight, for the backlash against equality rose early in the Northwest Territory states. In 1803 white politicians in the Ohio Territory – some of whom had been elected by African American citizens-- created a state constitution that added the word “white,” denying the right to vote to their own neighbors. Every state carved out of the Northwest territory followed suit. Anti-immigration laws, school segregation laws and other prejudiced “Black Laws” were enacted, profoundly affected the tens of thousands of free African Americans who were founding citizens of the region.

But African Americans across the region refused to give up. They believed in a nation where all should have an equal right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. They organized, holding “Colored Conventions,” where they worked to abolish slavery and regain the rights, including the right to vote, that had been taken from them. The 1848 convention in Cleveland, Ohio even devoted attention to women’s rights, and allowed women to participate in the proceedings.

Library of Congress

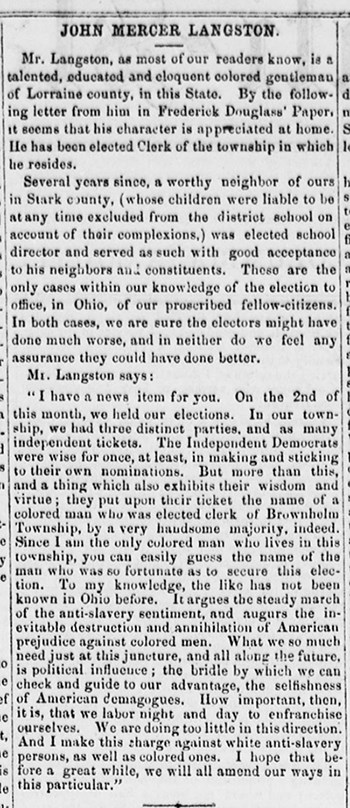

Chronicling America, Library of Congress

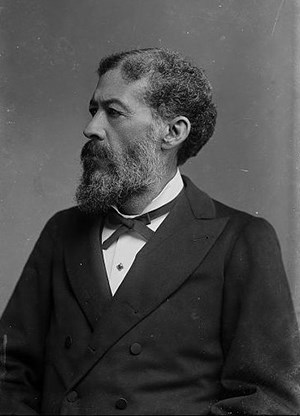

Several years since, a worthy neighbor of ours in Stark county, (whose children were liable to be at any time excluded from the district school on account of their complexions,) was elected school director and served as such with good acceptance to his neighbors and constituents. These are the only cases within our knowledge of the election to office, in Ohio, of our proscribed fellow-citizens. In both cases, we are sure the electors might have done much worse, and in neither do we feel any assurance they could have done better.

Mr. Langston says:

“I have a news item for you. On the 2nd of this month, we held our elections. In our township, we had three distinct parties, and as many independent tickets. The Independent Democrats were wise for once, at least, in making and sticking with their own nominations. But more than this, and a thing which also exhibits their wisdom and virtue; they put upon their ticket the name of a colored man who was elected clerk of Brownhelm township, by a very handsome majority, indeed. Since I am the only colored man who lives in this township, you can easily guess the name of the man who was so fortunate to secure this election. To my knowledge, the like has not been known in Ohio before. It argues the steady march of the anti-slavery sentiment, and the augurs of the inevitable destruction and annihilation of the American prejudice against colored men. What we so much need just at this juncture and all along the future is political influence; the bridle by which we can check and guide our advantage, the selfishness of American demagogues. How important, then, it is, that we labor night and day to enfranchise ourselves. We are doing too little in this direction. And I make this charge against white anti-slavery persons, as well as colored ones. I hope that before a great while, we will amend our ways in this particular.”

Note: Charles Grier’s burial in Gibson County, Indiana and the Union Literary Institute in Randolph County, Indiana are listed in the National Park Service, National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Further Reading:

Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2009).Cheryl LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013).

Stephen Middleton, The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2005).

Tiya Miles, Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits (New York: New York Press, 2017).

Leonard Richards, Gentlemen of Property and Standing: Anti-Abolition Mobs of Jacksonian America (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1971).

Silvana Siddali, Frontier Democracies: Constitutional Conventions in the Old Northwest (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Derrick Spires, The Practice of Citizenship: Black Politics and Print Culture in the Early United States (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

Nikki Taylor, Frontiers of Freedom: Cincinnati’s Black Community 1802-1868 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2005).

Stephen Vincent, Southern Seed, Northern Soil: African American Farm Communities in the Midwest, 1765-1900 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000).

Juliet E. K. Walker, Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1983).

Dana Weiner, Race and Rights: Fighting Slavery and Prejudice in the Old Northwest, 1830-1870 (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2013).

Anna-Lisa Cox is an award-winning American historian whose original research underpinned two exhibits at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Her writing has been featured in a number of publications including The Washington Post, Lapham’s Quarterly and The New York Times. Her newest book The Bone and Sinew of the Land was honored by the Smithsonian Magazine as one of the best history books of 2018, Professor Henry Louise Gates Jr. praised it for being “a revelation of primary historical research that is written with the beauty and empathic powers of a novel.” Dr. Cox is currently a Non-Resident Fellow at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Last updated: September 14, 2020