Last updated: January 23, 2020

Article

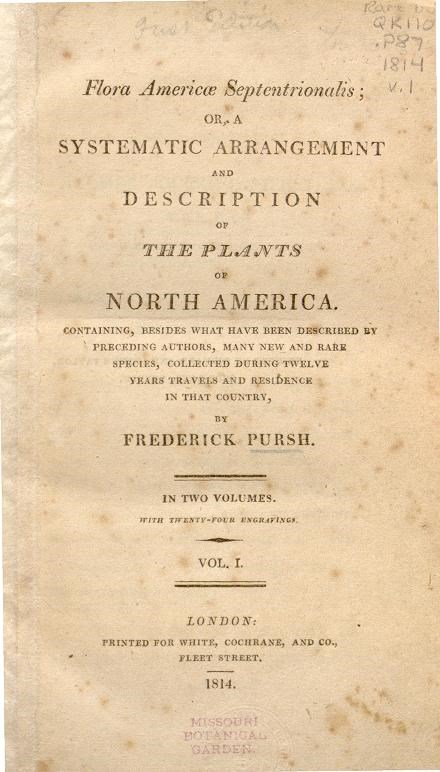

Frederick T. Pursh

Photo: Missouri Botanical Garden

When the first boxes of flora specimen that were shipped back on the keelboat from Fort Mandan were delivered to Thomas Jefferson in 1805, he certainly sent them on to Barton in Philadelphia. But it seems that Barton did nothing with them. When Lewis returned from the west in 1806, Jefferson urged him to begin immediately to prepare his journal for publication, and to arrange for Barton to begin work on the natural history.

It was likely at this point that Lewis realized Barton had done nothing. Why he was uninterested has been debated – it could have been poor health or simple unwillingness. Apparently it was the noted gardener and seed merchant, Bernard McMahon who, on April 5, 1807, recommended that Lewis contact Frederick T. Pursh to examine the Expedition's plants. Pursh was Barton’s part-time curator and collector.

Lewis met with Pursh in Philadelphia in April 1807 and the botanist was hired to begin a catalogue of the Expedition’s flora. Limited progress was made on the specimens before Lewis’s unfortunate death in October 1809. Ultimately, Pursh had a falling out with Barton and left for New York, then London. He took all of the Lewis and Clark plant collection, the notes, and his drawings with him.

When William Clark picked up the project of publishing the journals in 1810, he began searching for the plant specimens. He found some with McMahon, and was informed that Pursh had the rest. Clark paid for Pursh’s drawings, but it’s unclear if the specimens were ever returned.

Pursh continued working on publishing his own book, “Flora Americae Septentrionalis,” which was released in December 1813. The two-volume work was a modest success, but was quickly surpassed in popularity by the work of Thomas Nuttall: “Genera of North American Plants.” By 1818, Pursh was in Canada, living off a meager income. A long-time alcoholic, he was in poor health and died a pauper in Montreal on July 11, 1820.