Last updated: November 4, 2022

Article

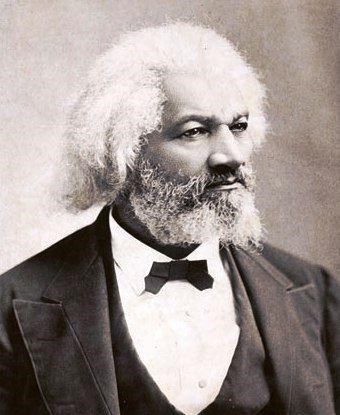

Frederick Douglass and the Civil War

Library of Congress

Frederick Douglass was born into a life of slavery on Maryland's Eastern Shore as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in February, 1818. He was mistakenly taught to read at an early age, and by his mid-teens was educating other slaves.

After one failed escape attempt at age 15, Douglass escaped to New York on September 3, 1838, where he declared himself a free man and turned his efforts to helping those still held in bondage. As an anti-slavery speaker, he caught the attention of William Lloyd Garrison, one of America's most prominent abolitionists, who soon had Douglass touring the country speaking against slavery on behalf of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

Douglass was such an impressive speaker that many people doubted he was truly a fugitive slave. Douglass responded with his first autobiography, the wildly successful The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, in which he revealed his original name, his owner's names, and where he was born. However, with his identity known and in danger of being returned to slavery, he fled to Great Britain.

Douglass so impressed his supporters in Britain that they purchased his freedom, allowing him to return to the United States two years later a legally free man. He settled in Rochester, New York, where he bought a printing press and began publishing The North Star, which became the nation's preeminent anti-slavery newspaper.

In 1861 tensions over slavery erupted into civil war, which Douglass argued was about more than union and state's rights. He saw the conflict as the seismic event needed to end slavery in America. Douglass knew that this new freedom had to be won both on and off the battlefield. He recruited African Americans to fight in the Union army, including two of his sons, and he continued to write and speak against slavery, arguing for a higher purpose to the war. He met with Abraham Lincoln to advocate for African American troops and to encourage Lincoln to see the war as a chance to transform the war aims to include emancipation of the nation's four million slaves.

Following the end of the Civil War, Douglass moved from Rochester to Washington, D.C., eventually buying his home at Cedar Hill. He served as the U.S. Marshall for the District of Columbia, the District's Registrar of Deeds, and the U.S. Minister to Haiti and Charge d'Affairs to the Dominican Republic, and he continued to work to expand civil rights in the United States country until his death in 1895.