Last updated: November 27, 2017

Article

Historical Photographs in the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site Museum Collection

NPS Photo

By Meagan Huff, Assistant Curator

Photographic portraits, unlike painted or sketched portraits, offer us an unflinching, realistic window into the past. From the historic photographs in the collection of Fort Vancouver, we can learn how people dressed, how they wore their hair, how they posed for photographs, and who they chose to be photographed with. The park’s collection also shows the variety of types of photographs made, including daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, and ivorytypes. Examining these photographs offers insight into the period in which they were made and can also be used to predict the conservation issues that will arise as they age.

To make daguerreotypes, early photographers first coated a copper plate with silver and placed the plate in a box where it was exposed to iodine vapors. Five to thirty minutes later, the plate was removed, its surface now covered with a light-sensitive silver-iodide film. The plate was then placed in a camera and exposed to light.

Early exposure times could range from five to seventy minutes, but technological developments in the 1840s reduced exposure times to under forty seconds, making the daguerreotype a more practical portraiture method.

After exposure, the plate was placed in an enclosed box, which held the plate at a 45 degree angle over a pan of heated mercury. Vapors from the heated mercury caused the plate’s image to emerge. The plate was then washed, toned in a bath of gold chloride, and dried. After drying, daguerreotype images were sometimes hand-colored, then placed inside a case. Daguerreotype images are direct positives, meaning that their images are reversed (though this problem is easily solved by flipping the glass plate over).

The glass panes used to cover 19th century daguerreotypes are inherently unstable and prone to decomposition. Three daguerreotypes from the Fort’s collection recently underwent conservation treatment and, as a part of this treatment, their deteriorating glass panes were replaced with more stable ones made of borosilicate glass.

Daguerreotypes are easily recognizable due to their mirror-like surface, a product of the silver coating on the plate. Reflections on this surface can make daguerreotypes difficult to view. This difficulty may have contributed to the development of photographic methods that produced images that were easier to see—like the ambrotype.

Photographic portraits, unlike painted or sketched portraits, offer us an unflinching, realistic window into the past. From the historic photographs in the collection of Fort Vancouver, we can learn how people dressed, how they wore their hair, how they posed for photographs, and who they chose to be photographed with. The park’s collection also shows the variety of types of photographs made, including daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, and ivorytypes. Examining these photographs offers insight into the period in which they were made and can also be used to predict the conservation issues that will arise as they age.

Daguerreotypes

Though some can be dated from the 1860s and later, daguerreotypes were most commonly produced between 1839 and the late 1850s. Daguerreotypes in the Fort Vancouver collection date from this period, and include portraits of Dr. John McLoughlin and his wife, Marguerite.To make daguerreotypes, early photographers first coated a copper plate with silver and placed the plate in a box where it was exposed to iodine vapors. Five to thirty minutes later, the plate was removed, its surface now covered with a light-sensitive silver-iodide film. The plate was then placed in a camera and exposed to light.

Early exposure times could range from five to seventy minutes, but technological developments in the 1840s reduced exposure times to under forty seconds, making the daguerreotype a more practical portraiture method.

After exposure, the plate was placed in an enclosed box, which held the plate at a 45 degree angle over a pan of heated mercury. Vapors from the heated mercury caused the plate’s image to emerge. The plate was then washed, toned in a bath of gold chloride, and dried. After drying, daguerreotype images were sometimes hand-colored, then placed inside a case. Daguerreotype images are direct positives, meaning that their images are reversed (though this problem is easily solved by flipping the glass plate over).

The glass panes used to cover 19th century daguerreotypes are inherently unstable and prone to decomposition. Three daguerreotypes from the Fort’s collection recently underwent conservation treatment and, as a part of this treatment, their deteriorating glass panes were replaced with more stable ones made of borosilicate glass.

Daguerreotypes are easily recognizable due to their mirror-like surface, a product of the silver coating on the plate. Reflections on this surface can make daguerreotypes difficult to view. This difficulty may have contributed to the development of photographic methods that produced images that were easier to see—like the ambrotype.

NPS Photo

Ambrotypes

Ambrotypes were most commonly produced between 1852 and 1881. In looking at Fort Vancouver’s collection of historic photographs, it becomes obvious that ambrotypes postdate daguerreotypes. While Dr. McLoughlin’s portrait was taken as a daguerreotype, portraits of his grandchildren, believed to have been taken in the 1860s, are ambrotypes.Ambrotypes are somewhat similar to daguerreotypes. Both types are direct positive images and are usually found in decorated cases with mats and preservers. However, ambrotypes, unlike daguerreotypes, are produced by a different chemical process and do not have a mirror-like surface, which allows for easier viewing.

To create an ambrotype, a photographer used a “wet-plate” collodion process, in which a glass plate was first coated with a light-sensitive mixture of gun cotton, ether, and alcohol, then soaked in silver nitrate. The plate was placed in a camera, purposefully underexposed, and developed, all while still wet. The ambrotype process produced a faint negative image on the plate. When the finished plate was placed in a case, it was backed with black material, which could be lacquer, cloth, paper, or metal, to make the image appear positive.

Over time, the black lacquer that backs some ambrotype images can flake, and this was the case for a number of the park’s recently conserved ambrotypes. Conservators resolved this problem by placing a piece of archival-quality, PAT-tested black paper behind the plate. This paper will help to preserve both the image

NPS Photo

Tintypes

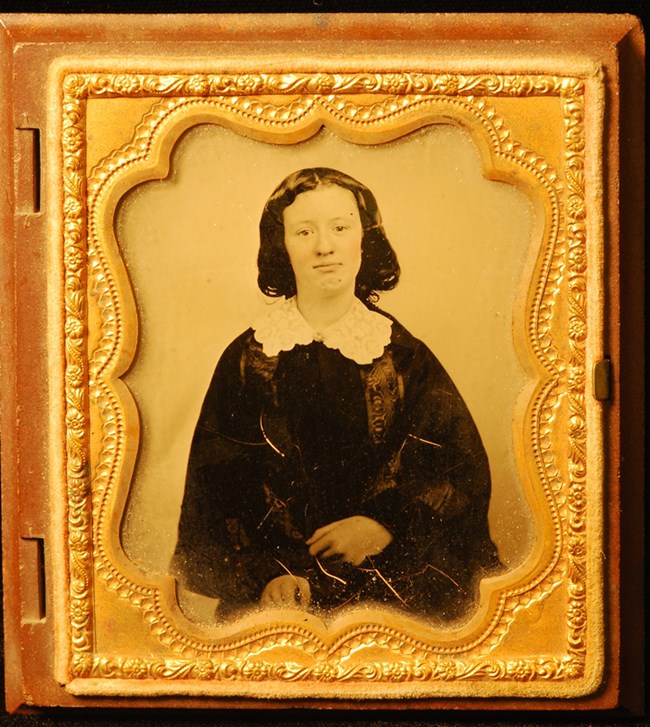

Tintypes, most commonly produced in the last half of the 19th century, were produced using the same “wet-plate” collodion process as ambrotypes. However rather than a glass plate, images were exposed onto thin sheet iron that had been lacquered black or brown.Though some tintypes were placed in cases like daguerreotypes or ambrotypes, they were more often simply mounted on paper mounts or left loose. Because of this, tintypes are often found bent, which can cause their emulsion to crack and flake. Fort Vancouver’s tintype of an unidentified young girl from the McLoughlin family has been placed in a case under a glass pane, protecting it from this kind of damage.

NPS Photo