Part of a series of articles titled The Cultural Landscape of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Article

The Cultural Landscape of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site: Hudson's Bay Company, 1824-1846

NPS Photo

Administrative and Political Context

Chartered by the British crown since 1670, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) dominated the fur trade in Canada, and later the Western territories, for two hundred years. Based out of the Hudson Bay region, the English fur trade monopoly encompassed 1.5 million square miles of territory between Russian Alaska and Mexican California. To keep up with a growing fur market and the shrinking supply of beaver pelts, HBC extended their range to interior western lands. In 1821, HBC acquired four trading posts in the Columbia Basin region from their rival company North West Company when the two businesses merged: Fort George at the Columbia River mouth, Fort Nez Percé, Spokane House, and Kootenai House. As these depots were unprofitable, HBC directed George Simpson to survey the region and recommend a course of action. Simpson did so, and in late 1824 he selected Jolie Prairie at the current Vancouver National Historic Reserve area as the site for the new Fort Vancouver.

Simpson's choice of a site on the north side as opposed to the south side of the Columbia River was likely a political strategy to keep the territory north of the Columbia River under British rule. Although the British-American War of 1812 ended in 1814 with the Treaty of Ghent, the treaty did not resolve the disputed claims of Great Britain and the United States to the entire territory west of the Rocky Mountains. The principal disagreement centered on the location of the boundary between Canada and the United States. Great Britain proposed the boundary follow the 49th parallel from the Rockies westward until it intersected the Columbia River, then follow the river southwest to the Pacific Ocean. The United States wanted the boundary to continue along the 49th parallel until it met the ocean - the current boundary between Canada and the United States. The two countries suspended negotiations in summer 1824, leaving final settlement of the disputed land between the 49th parallel and the Columbia River unresolved. The Hudson's Bay Company's establishment of Fort Vancouver later that same year reinforced Great Britain's claim to the undecided territory.

Within a decade, Fort Vancouver became the HBC Columbia Department's main supply post and administrative headquarters and the center of all HBC activities west of the Rockies, including international trade. Simpson decided to develop a sizeable agricultural operation to both supply the fort's needs as well as to augment the company's profitable export business. He appointed John McLoughlin as Chief Factor to oversee the fort's operations, and for twenty years McLoughlin managed a vast trade enterprise that extended from Alaska and the Rockies to California and Hawaii. Fort Vancouver's economic, political, and social influence peaked in the years between 1829 and 1846 as the fort became the manufacturing and agricultural hub of the Pacific Northwest. Agricultural activity intensified while the fur trade declined, and early industrial operations developed at the HBC fort, including salmon fisheries, large-scale timber milling, and grain milling. During this period, Fort Vancouver welcomed numerous travelers, explorers, missionaries, and scientists, including renowned Scottish botanist David Douglas and botanist Dr. Thomas Nuttall.

Fort Vancouver was instrumental in American westward expansion by providing pioneers the necessary provisions to establish farms across the Pacific Northwest from Puget Sound to the Willamette Valley. Starting in 1842, pioneer emigrants flooded into the area on the Oregon Trail. This mass wave of American settlement dampened British hopes of establishing control over the lower Columbia Basin. Finally the 1846 Oregon Treaty settled the boundary dispute in the United States' favor and signaled the end of the HBC period.

Site Description

Prevailing political forces may have influenced George Simpson's selection of the new fort site, however Simpson deemed the site known as Jolie Prairie ("pretty meadow") most suitable for Fort Vancouver on the basis of physical landscape features. Six miles from the confluence with the Willamette River, the post was located on an easily defensible position one mile from the Columbia River on a bluff overlooking the river and the low plain below. The site's strategic position on the region's principle navigable waterway supported the company's extensive trade network in the interior lands as well as international trade. Listed high on Simpson's reasons, however, was that the lower plain appeared suitable for extensive cultivation. Numerous writings attest that Simpson chose the north location because the soil and climate would support large-scale farming operations. John McLoughlin noted that it "...was a place where we could cultivate the soil and raise our own provisions." Shortly after viewing the site for the new fort, George Simpson wrote in his journal:

Simpson's description supports the assertion that the site had been modified by Native American land practices in a manner subsequently conducive to Euro-American settlement. His references to "good pasture" and "nutritious roots" (probably camas) suitable for pigs, combined with Alexander Henry's account of fire and subsequent grass growth on the site a decade earlier, are consistent with ethnohistorical and ethnobotanical accounts of prescribed burning. The site consisted of floodplain terraces stepping back from the Columbia River. According to Alexander Henry's 1814 observations and Simpson's 1824 reconnaissance, the land adjacent to the river was low and often under water (three miles long by three-quarter mile wide); the next terrace was high prairie ground rising up about thirty feet (two miles long by two miles wide); and dense coniferous forest rose sixty feet above it. Simpson also noted two lakes located in the center of the plain and occasionally inundated by spring floods.The place we have selected is beautiful as may be inferred from its Name and the Country so open that from the Establishment there is good traveling on Horseback to any part of the interior; a Farm to any extent may be made there, the pasture is good and innumerable herds of Swine can fatten so as to be fit for the Knife merely on nutricious [sic] Roots that are found here in any quantity and the Climate so fine that Indian Corn and other Grain cannot fail of thriving...The distance from the Harbour is the only inconvenience but that is of little importance being now a secondary establishment...at the Jolie Prairie or Belle vue Point where the New Fort is situated it may be from time to time enlarged without the trouble of felling a tree.

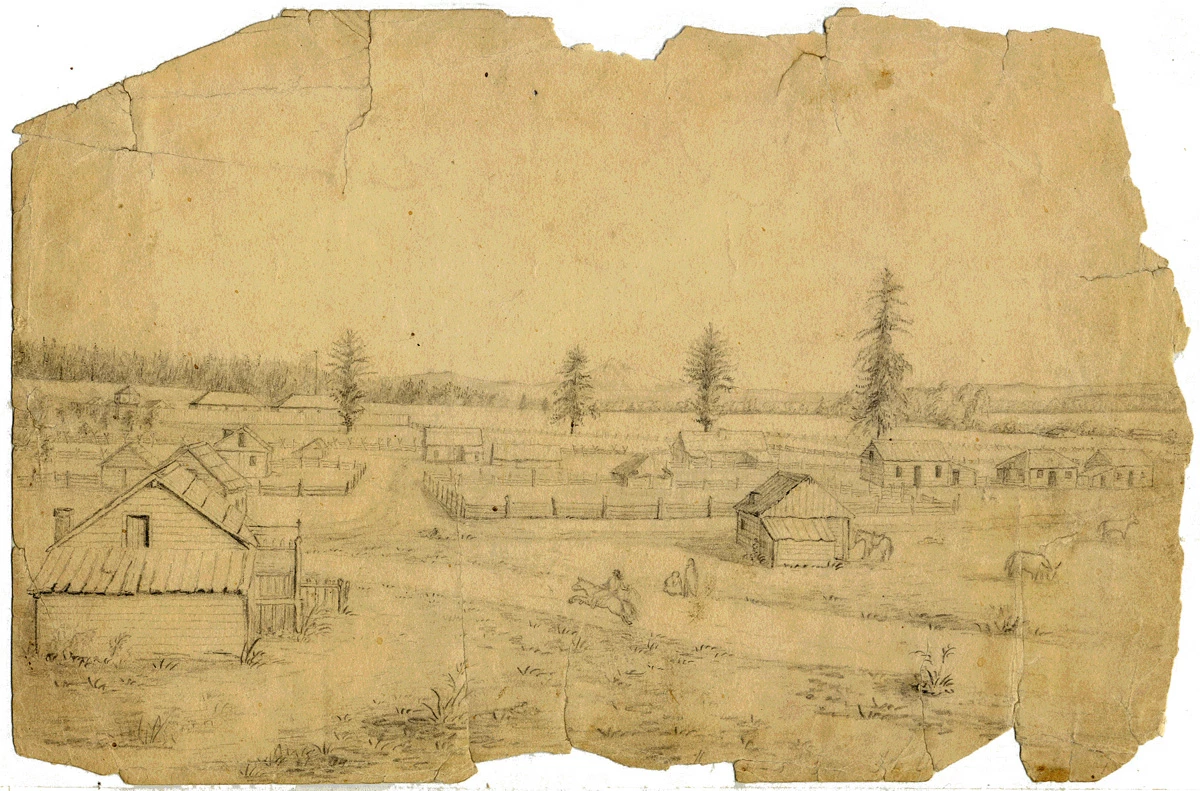

Archaeological study has not yet uncovered the exact location of this first fort, however early maps show that it was in the vicinity of E Grand and E 6th Street. The fort was originally built on the upper plain of a bluff overlooking the lower plain; this location was chosen due to its protected position and the company's concern over potential hostile relations with native peoples. Simpson related that "The Establishment is beautifully situated on the top of a bank about 1-1/4 Miles from the Water side commanding an extensive view of the River the surrounding Country and the fine plain below which is watered by two very pretty small Lakes and studded as if artificially by clumps of Fine Timber." The original site was abandoned when concerns about possible conflict proved unfounded, and the one-mile distance for obtaining water and shipping goods became too inconvenient. In the winter 1828-29, HBC officials moved the fort stockade within 400 yards of the river on the lower plain one-mile west of the fort's original location.

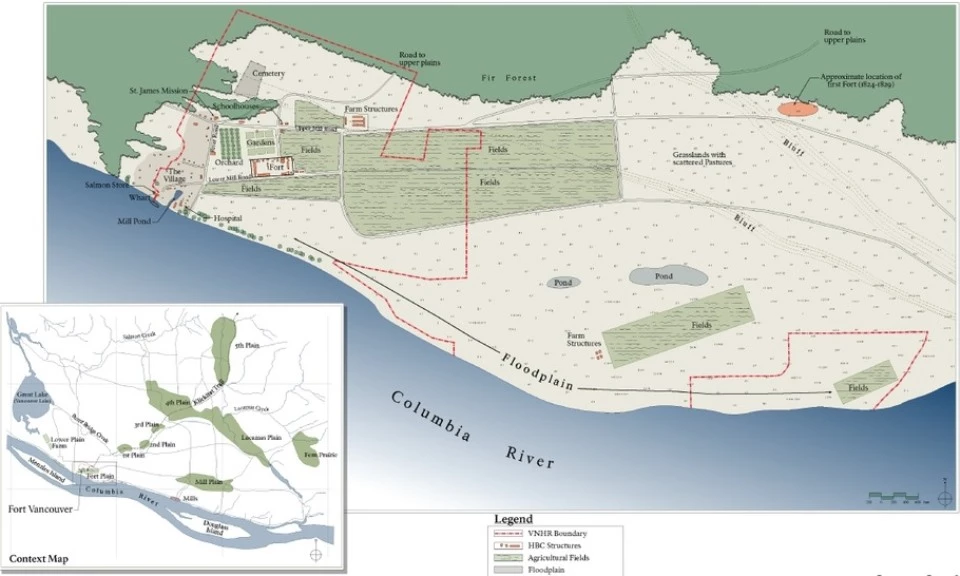

Fort Vancouver developed to its greatest extent by the 1840s. Hudson's Bay Company farmland comprised three large meadows, named Fort Plain, Lower Plain, and Mill Plain, nestled in a forest along the Columbia River. Fort Plain (alaëi'k-aë or turtle place) and Mill Plain (tij - no translation) were located on original prairies most likely maintained by lower Columbia tribes prior to HBC establishment. Additionally, there were five plains north and east of the three primary fort plains, typically called the "back plains," which intermittently supported crops. Dense coniferous forests defined the boundaries of the Fort Plain, and on the plain's northwest edge, a band of forest extended nearly to the river's edge.

NPS Photo

Landscape Characteristics

Natural Systems and Vegetation

The abundant availability of natural resources provided an optimal site for successful fur-trading and agricultural enterprise. The site's strategic location on the Columbia River and its surrounding natural resources were prime factors that attracted the Hudson's Bay Company. Key natural resources included the Columbia River and major streams for transportation; a mild, maritime climate and good soils for farming; large grasslands with livestock potential; plenty of timber for building; and open space in the midst of impenetrable forests to accommodate fort development.

Several people visited and documented the vegetation of Fort Vancouver in its early years. Early explorers observed the site's unique prairie-forest composition before and after the fort's construction. Pioneer settlers approvingly appraised prairies as useful places for livestock grazing and agriculture operations, while forests provided the necessary building materials.

George Simpson described the natural vegetation in the region west of the Cascade Range after his winter 1824-25 trip up the Columbia River to Jolie Prairie: "The banks of the Columbia on both sides from Capes Disappointment and Adams to the Cascade portage a distance of from 150 to 180 Miles are covered with a great variety of fine large timber, consisting of Pine of different kinds, of Cedar, Hemlock, Oak, Ask, Alder Maple and Poplar with many other kinds unknown to me."

After his 1825 visit, John Scouler wrote:

It is situated in the middle of a beautiful prairie, containing about 300 acres of excellent land, on which potatoes and other vegetables are cultivated; while a large plain between the fort and river affords abundance of pasture to 120 horses, besides other cattle...The forests around the fort consists chiefly of Pinue balsamea & P. canandensis (trees since identified as Psuedotsuga douglasii and Picea sitchensis). Within a short distance of the fort I found several interesting plants, as Phalagium escluentum, Berberis nervosa, B. Aquifolium, Calypso borealis & Corallorhiza innata. The root of the Phalangium esculentem (bulb since identified as Camassia quamash or camas) is much used by the natives as a substitute for bread. They grow abundantly in the moist prairies, the flower is usually blue, but sometimes white flowers are found.

Fellow traveler Scottish botanist David Douglas also visited Fort Vancouver in April 1825 and remarked that:

Extensive natural meadows and plains of deep fertile alluvial deposit are covered with a rich sward of grass and a profusion of flowering plants...my labour in the neighborhood of this place was well rewarded by Ribes sanguineum (currant), Berberis aquifolium (tall Oregon grape), Acer macrophyllum (bigleaf maple), Scilla esculenta (Camassia quamash, camas), Pyrola aphylla (leafless pyrola), Caprifolium cilosium (Lonicera cilosium, honeysuckle), and a multitude of other plants.

Spatial Organization

The fort palisade, the employee village, agricultural fields, roads, mills, and farm clusters were organized around the regional natural systems, vegetation, and topography. The Columbia River and its floodplain geomorphology essentially influenced the development of the fort site in this time period and subsequent periods. The open prairie area in the midst of dense coniferous landscape on the shores of the Columbia River provided a strategic location for the HBC post. The river benches helped define the location of developed areas such as the fort, while floodplain soils on the prairies previously burned by Lower Columbia tribes provided optimal pastures, fields, and agriculture lands. The fort palisade, internally focused and delineated by the stockade fence, occupied a central position on the lower plain just above the river. It was the hub from which all activity radiated. Roads spiked away from the palisade to the river, employee village, agricultural fields, and upper Plains. Developments such as the fort, farm buildings, the village, and the mission, were organized in cluster arrangements related to their immediate functions.

Land Use

Fort Vancouver was a full-scale manufacturing, agricultural, and trading center of the Pacific Northwest by 1846, and Simpson's vision of the HBC post as a regional and global trading center was realized. The Fort Plain lands functioned according to uses driven by this prominent industry; the HBC environs were utilized for extensive agriculture, for industries related to the export trade business, and to meet the subsistence needs of the many residents. Residential areas, farm clusters, industrial areas, fields, pastures, and mills all developed to support this first large-scale Pacific Northwest trade post. As development proceeded, forests and prairies were cleared to make way for fields and farms.

The Columbia River was the primary transportation corridor that supported Fort Vancouver's trading and agricultural industries. Travel still occurred mainly by water during this period, and people and goods arrived and departed Fort Vancouver via boat. The waterfront was thus an active place, and an important nexus between the fort site and the river.

Circulation

Development of roads, paths, and water routes was largely driven by the fort's function as a fur-trading and agricultural post. Principal access to and from the site during this period was from the Columbia River. The Columbia River was the focal point of activity, and the primary transportation route for far-ranging trade and supply ships, as well as local travel. Hudson's Bay Company ships, London-based supply ships, and civilian and military trading ships traveled upriver from the Pacific Ocean. Verious river craft transported passengers and goods down river from The Dalles, while barges and boats brought passengers and goods from the Willamette River to the Columbia to the Company's wharf.

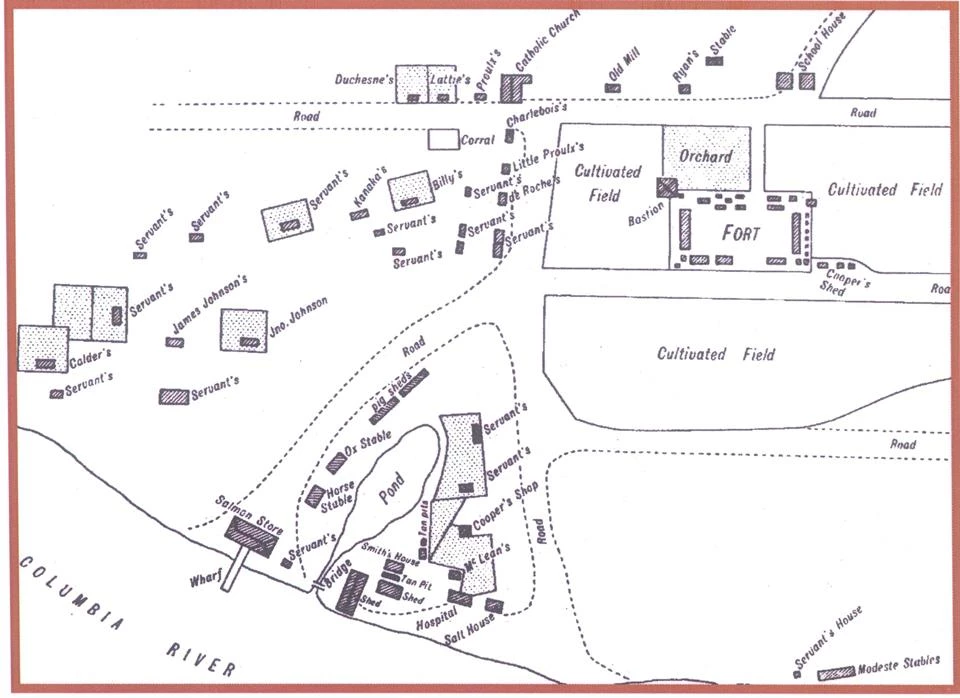

An 1825 map shows that the first road was constructed on a north-south axis from the Columbia River to the first fort site. This road allowed goods unloaded from ships at the waterfront to be transported up the bluff to the stockade's storehouses. Carting goods the nearly one-mile distance with wagons was an arduous process. The exact anchorage and staging area for the first fort is unknown, although a wharf was constructed southeast of the 1828-29 fort site within this time period.

Early maps illustrate conflicting information with respect to the road system development. An 1846 map by Richard Covington is fairly consistent with an 1844 map by Henry Peers, which shows the east-west Upper Mill Plain Road and the Lower Mill Plain Road, and a southeasterly road connecting the two mill plain roads. But these two maps differ from the 1845–46 Vavasour map in depicting the location of the southeasterly road in relation to the lower lakes. None of the 1840s maps indicate the connection between the Lower Mill Plain Road and the river.

NPS Photo

Buildings, Clusters, and Small-scale Features

Fort Vancouver was laid out in a series of clustered structures and features organized around the floodplain hydrology, topography, and vegetation patterns. Major clusters were arranged along the Columbia River and on naturally occurring open meadows; these principal clusters consisted of Fort Plain, Lower Plain, Mill Plain, the sawmill, the gristmill, as well as the Back Plains prairie series located north and east of the fort. Agriculture fields were initially tilled into existing open prairies on alluvial soils, and barns and utility sheds were adjacent to fields. Mills operated on streams emptying into the Columbia River, while sheds and workers’ housing were located nearby. The upland forests provided crucial building materials.

The Fort Plain contained several clusters: the stockade; the employee village; surrounding gardens, fields, and orchards; and the river front complex. The 1829 fort stockade was the center of the outfit with roads radiating out from the fort. The stockade cluster contained stores, warehouses, offices, and officer residences. Other structures and agricultural operations built up around the HBC fort: schools, stables, a cemetery, a church, garden, orchard, and cultivated fields.

A large, multi-cultural village (sometimes referred to as Kanaka Village or the Village) developed west of the fort and was comprised of several employee residences, some with enclosed gardens. Fort Vancouver attracted numerous people from distant places. American Indians from the east coast and Canada, native Hawaiians, French Canadians, English, Scots, and Metís came to Fort Vancouver, and created a very diverse community at Fort Vancouver’s employee village. South of the village was a cluster of structures arranged around a pond connected to the Columbia River; these were predominantly utilitarian structures such as stables, cooper’s shop, saw, and tanning pits. The southern edge of this cluster included the salmon house (store) leading to a wharf, a warehouse, a hospital, and a salt house.

Last updated: March 6, 2020