Part of a series of articles titled The Cultural Landscape of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Article

The Cultural Landscape of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site: Fort Vancouver and Vancouver Barracks, 1847-1860

NPS Photo

Excerpted from Vancouver National Historic Reserve Cultural Landscape Report. For more information on this report, email us.

Administrative and Political Context

By June of 1846, the Oregon Treaty between the United States and Great Britain was finally settled, establishing the boundary between the United States and Canada at the 49th parallel. This period was a time of social, political, and economic upheaval for controlling

British interests in the area, as American influence over the territories was growing stronger. In the wake of the treaty, the most significant event highlighting this period was the arrival of the United States Army in 1849.

Under the command of Brevet Major J. S. Hathaway, two companies of the U.S. Army’s First Artillery arrived in Oregon on May 9, 1849, to fulfill the federal government’s guarantee of protection for settlers. Fort Vancouver witnessed the infiltration of a great number of American settlers who were moving westward to lay claim to surrounding lands. Additionally, the settlement of the treaty granted the employees of the HBC, as well as all subjects of the British crown, a certain amount of “possessory rights” to all who had legally acquired land. The premise of the treaty, underscored by the presence of the U.S. Army, was to entitle both parties to usage rights within areas of the territory. The spirit of the treaty also presumed peaceful and mutual coexistence between parties. However, the harmony between countries only lasted a few short years, and soon distrust, jealousy and fighting ensued. As the American presence in the area rapidly increased, Great Britain and the HBC lost all controlling interest and with it, any practical claim to territory.

Other events also hastened the decline of the HBC during the period of 1846–49. As the fever of the gold rush and the promise of striking it rich swept westward, HBC employees decreased by nearly two thirds as many headed south toward California in search of gold. By 1850 the fur trading industry was on the decline, and as such, became an insignificant source of revenue for the Company. These events, coupled with the strained relations between the U.S. soldiers and Company employees, forced HBC to vacate the post by 1860.

Charles Williams Wilson, a royal engineer with the British Northwest Boundary Commission, described the degree of resentment felt by the British employees still posted at the fort. He wrote on May 1, 1860:

The fort is now surrounded by the Garrison of American troops under General Harney of San Juan renown; alas the poor old Fort once the great depot of all the western fur trade is now sadly shorn of its glories, General Harney having taken forcible possession of nearly all the ground round & almost confined the HBC people to the fort itself; the HB Company are going to give up their post here as most of their business is now transacted in Victoria & in consequence of General Harney’s disregard of the treaty of 46 which secured them their rights; it is most annoying to them to see all the fields & land they have reclaimed from the wilderness & savage gradually taken away from them; we have at present the use of the buildings which are nearly empty now, what a place it must have been in the olden time.

Following nine years of negotiation, a final settlement was reached on June 9, 1860, and the HBC relinquished all claims to the property. Upon reaching the settlement, the U.S. Army immediately established the property as its own and established a military reservation that encompassed approximately four square miles.

In addition to the territory claims made by the U.S. Army, the Catholic Church’s Bishop of Nisqually filed a claim in 1853 for 640 acres of land for St. James Catholic Church. Although protests to the survey general were made against the claim, citing that the church already occupied company land, the request was approved as a provision in the act of Congress on March 3, 1853. Shortly thereafter a mission was requested, and under the care of a handful of religious clergy, a school, hospital, and orphanage were all in operation by 1857.

The stage was set for the next chapter in the subsequent development of the Reserve. As the Hudson’s Bay Company abandoned the fort, packed up, and headed north to Victoria, the site was now left to the U.S. Army to make their landscape impressions. Fort Vancouver, once a profitable fur trading and agricultural hub, was ready to complete its transition to a military installation outpost.

Site Description

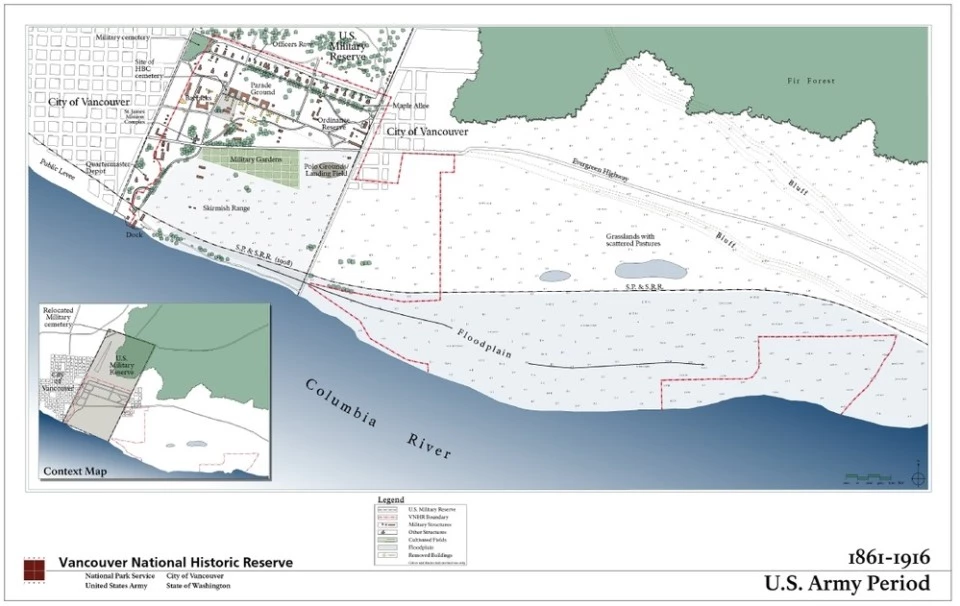

The U.S. Army claimed a four-square-mile military reserve including the lands containing the HBC fort, employee village, and about two miles on either side of the core developed area. Congress later reduced the size of the reserve to 640 acres in 1853. The resulting transfer of land ownership to the U.S. Army and the Mission of St. James prompted a significant change in Fort Vancouver land patterns. Between 1857 and 1858 the landscape surrounding the HBC stockade was greatly altered, particularly with respect to Kanaka Village and the riverfront, where company buildings, gardens and other structures were falling into disrepair. As a result these HBC structures were removed from the landscape.

The orchards west of the company gardens were destroyed in an 1844 fire. The Mansfield map shows that by 1854 the orchard was divided and shifted to the north; the garden was called “soldiers garden,” indicating that the U.S. Army operated the former HBC garden by this time. While the land itself was not substantially altered in its agricultural use, the configuration and location of many of the field patterns were repositioned. The field locations intensified around the stockade, and extended out to the north and east, yet remained constrained by the river and the northeast bluffs.

The transition from trading post to military post spurred significant new site developments. The U.S. Army constructed Officers’ Row, various military post structures, the Parade Ground, and new roads during this period. The City of Vancouver grew up along the west boundary of the military post, and was officially incorporated in 1857.

NPS Photo

Landscape Characteristics

Natural Systems and Vegetation

Paul Kane, an artist commissioned in 1847 to provide a visual record of the surrounding area of the fort and the stockade, wrote the following description of the site:

The surrounding country is well wooded and fertile the oak and pine being of the finest description. The camas and “wappatoo” are found in immense quantities in the plains in the vicinity of Fort Vancouver, and in the spring of the year, present a most curious and beautiful appearance, the whole surface presenting an uninterrupted sheet of bright ultra marine blue, from the innumerable blossoms of these plants.

Likewise a few years later in 1850, a visitor to the Fort Vancouver area provided a general account of the countryside.

The timber upon the lowlands of the Columbia is chiefly cotton wood; in the smaller streams, vine maples and alder; while the upland is covered with the usual growth of the region of Oregon-fir, spruce and towards the mountains, arbor viate. This forest is almost entirely of secondary growth, and is deadened over a vast tract by the fires which run through the country. . . . The succession of forest which so universally takes place in the Atlantic States does not occur here, the few deciduous trees of the country being such as growth only upon the water-courses. As a consequence the first almost invariably spring up again when burnt off. The underbrush, consisting of hazel, spirea, & c., is unusually dense.

Both accounts provide an insightful glimpse into the condition of the landscape at the time for both the north and south portions of the site. There is a clear distinction between the north end of the site with respect to the density and variety of the forest as compared to the south end of the site (with its proximity to the water) that contained open fields for agrarian purposes. While more forest clearing certainly took place during this period to support HBC and U.S. military activities, the above passages document the native prairie-forest mosaic.

Spatial Organization

Following the decline of British influence over the stockade, Fort Vancouver was re-organized to suit the needs of U.S. military operations. The army constructed new buildings, roads, and the Parade Ground during this period; this basic framework established the site’s spatial organization that persisted in subsequent historic periods.

The northern part of the site, with its favorable vantage point overlooking the lower floodplain and the Columbia River, became the focal point for the military post. Officers’ Row, the primary core of residences for officers, was constructed in linear progression along the upper floodplain terrace. Officers’ Row framed the northern edge of the Parade Ground, and an interior road encircled the Parade Ground. This central area became the public node for both military and civilian social activities. Fields and pastures were re-organized so that they completely surrounded the stockade, and the orchards shifted to the northwest.

Land Use

Following the U.S. military’s claim to the HBC fort and surrounding land, the center of activity shifted north to the new army garrison. The most prominent developments at this time were the establishment of the Parade Ground and the military housing quarters along the northern end of the site known as Officers’ Row. The Parade Ground was centrally located within the reserve and designated for public ceremonial parades as well as military marching drills. A

correspondent for the San Francisco newspaper Daily Alta California wrote the following observation on January 29, 1865:

Outside the post boundary, the most striking alteration to the landscape in this period was the organized grid layout for the City of Vancouver to the west of the Army Barracks. Surveyed by J. B. Wheeler and J. Dixon in 1859, the city boundary extended northeast and southeast, demarcating the contrast between the orthogonal grid of the city and the river-oriented layout of the old British settlement. The rapid development of the new city resulted in the shift of commercial activity to the west.The Ninth Regiment is now stationed at Fort Vancouver and here the famous Shanghai drill is daily performed with a precision wonderful to behold. The officers are found quartered in comfortable houses. . . . They are, indeed, a splendid corps, mostly young, fine looking gentlemen, naturally eager for a brush with the Indian.

Circulation

Several major roads established by the HBC were still in use during this period; however, many minor circulation paths changed due to the relocation of farm fields. For example, Lower Mill Road on the south entrance was removed as a result of the northern shift of the planting fields, and the area became grassland with scattered pastures. Upper Mill Road (currently known as E 5th Street) continued to run in an east-west direction. To the west, the road traversed the north end of City of Vancouver, flanking the forested area and eventually moved down along to the river. To the east, it maintained much of the same route it had established earlier by the British. River Road continued its run north-south alignment that connected St. James Mission to the river.

The U.S. military also designed new roads during this era. Located west of River Road and south of the barracks, one new route ran in a southerly direction from St. James Mission to the company wharf, and to the west Quartermaster’s Depot buildings.

The new interior road system reflected the spatial organization of the military reserve. Circulation routes defined many of the key areas such as Officers’ Row, the Parade Ground, and the fields and orchards. These roads also branched off and progressed along a north south axis, which in essence connected the barracks to the City of Vancouver and the upper forests.

Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Buildings, Clusters and Small-scale Features

The arrival of nine more companies of American soldiers spurred the construction of twenty-six additional buildings in 1851. The army constructed buildings on three sides of the Parade Ground. At the northern boundary of the site, running parallel with the Parade Ground, new log housing was constructed known as Officers’ Row, taking advantage of the views to the lower part of the site and the Columbia River. The commanding officer’s residence was located in the center of the row of houses, and a flagpole was placed on the Parade Ground directly across from the commander’s house. Officers’ Row faced south toward the Parade Ground. On the western edge of the Parade Ground, a gabled roof log barrack and two smaller structures were erected. To the east, another barrack was constructed, accompanied by several smaller kitchens.

In the vicinity of the employee village, the army constructed a Quartermaster’s Depot, where in addition to leasing many of the existing buildings from HBC, they constructed five new buildings. Positioned west of the HBC village and assembled in a north-south alignment, the new buildings included the Quartermaster’s office and residence, Quartermaster employee residences, carpenter shop, storeroom and blacksmith shop. Along the Columbia River, a new wharf called Government Wharf was commissioned in the vicinity of the old docks.

Last updated: February 8, 2018