Last updated: March 29, 2023

Article

Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Under the early light of dawn, Union Adm. David Farragut began his attack on Mobile Bay, Alabama. Aware of the danger near Fort Morgan, Farragut ordered his captains to stay to the "eastward of the easternmost buoy" because it was "understood that there are torpedoes and other obstructions between the buoys."¹ Unfortunately, the lead ironclad, the USS Tecumseh, unable to avoid the danger, struck a mine and sank into the oceans depths. Yet, against all odds, the seasoned admiral ordered his flagship, the Hartford, and his fleet to press forward through the underwater minefield and into Mobile Bay.

Although Farragut was a champion of the "wooden navy," he agreed to include four new ironclad ships modeled after the USS Monitor in his attack fleet. It was widely believed that these warships were unsinkable. But the Tecumseh indeed sank that summer morning, August 5, 1864, unexpectedly killing the majority of its crew and demonstrating the deadly effects of advances in technology such as the torpedo. For in the words of one Confederate soldier reminiscing on the ill-fated ship, "She careens, her bottom appears! Down, Down, Down she goes to the bottom of the channel, carrying 150 of her crew, confined within her ribs, to a watery grave."¹

²"Fort Morgan in the Confederacy: Letter by Hurieosco Austill." Alabama Historical Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 2, (Summer 1945), 256.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Fort Morgan" (with photographs), and other sources. It was made possible by the National Park Service's American Battlefield Protection Program. The lesson written by Blanton Blankenship, Historic Site Director, Fort Morgan and Bill Rambo, Historic Site Director, Confederate Memorial Park. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in American history units on the Civil War or science and technology.

Time period: 1860s

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

Standard 2A- The student understands how the resources of the Union and Confederacy affected the course of the war.

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the social experience of the war on the battlefield and homefront.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard G - The student describes and analyzes the role of technology in communications, transportation, information-processing, weapons development, or other areas as it contributes to or helps resolve conflicts.Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard A - The student examines and describes the influence of culture on scientific and technological choices and advancement, such as in transportation, medicine, and warfare.

-

Standard E - The student seeks reasonable and ethical solutions to problems that arise when scientific advancements and social norms or values come into conflict.

Objectives for students

1) To determine why a major seaport like Mobile, Alabama was vital to the Confederacy and why a blockade or the removal of its defenses was critical to the Union.

2) To evaluate the effect of technology on the Battle of Mobile Bay.

3) To describe some of the technological advances that appeared during the Civil War and evaluate their impact on soldiers.

4) To discover if fortifications ever existed in their own community, to describe those fortifications, and to explain how changes in technology affected them.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-quality version.

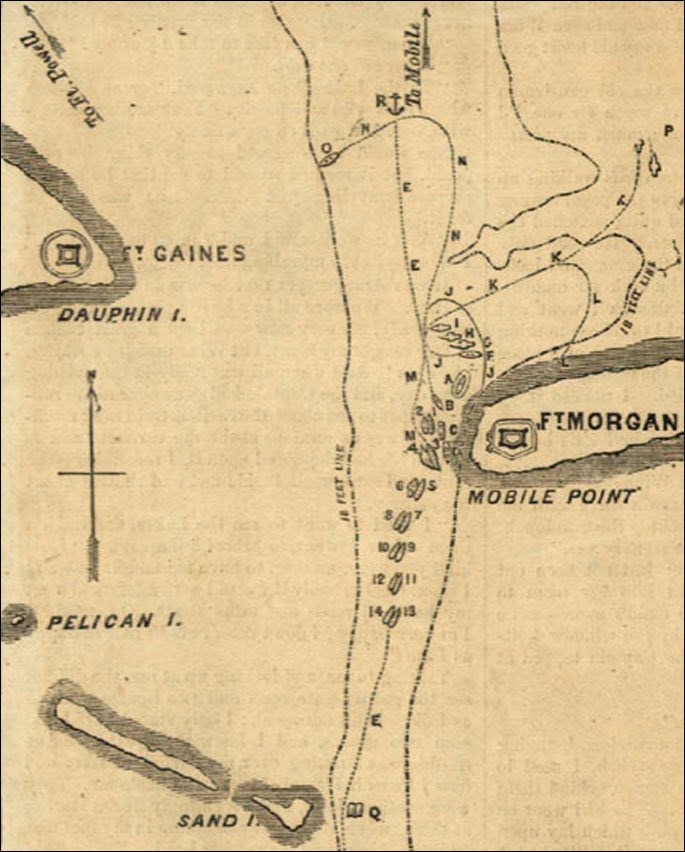

1) Two maps of the blockaded coastline of the Confederate States of America and of Mobile Harbor;

2) Three readings of firsthand accounts of the Battle of Mobile Bay and the developing maritime technology pertaining to the Civil War battles fought at sea;

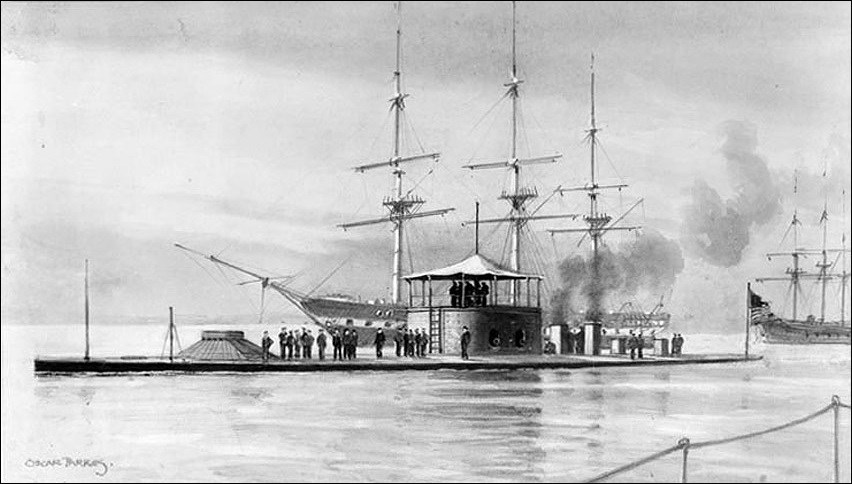

3) One drawing and one painting of a monitor warship;

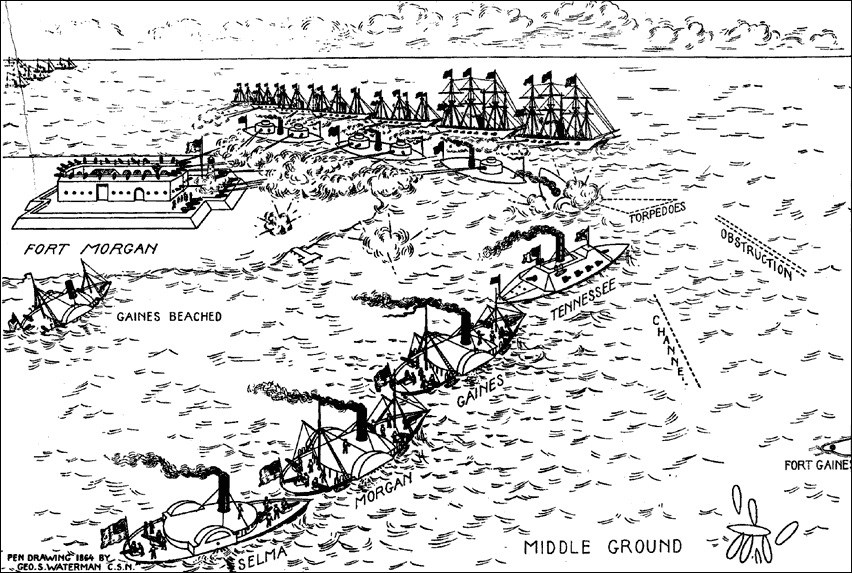

4) One drawing and one illustration of the battle scene and the routes of both the Confederate and Union fleets that participated in the Battle of Mobile Bay;

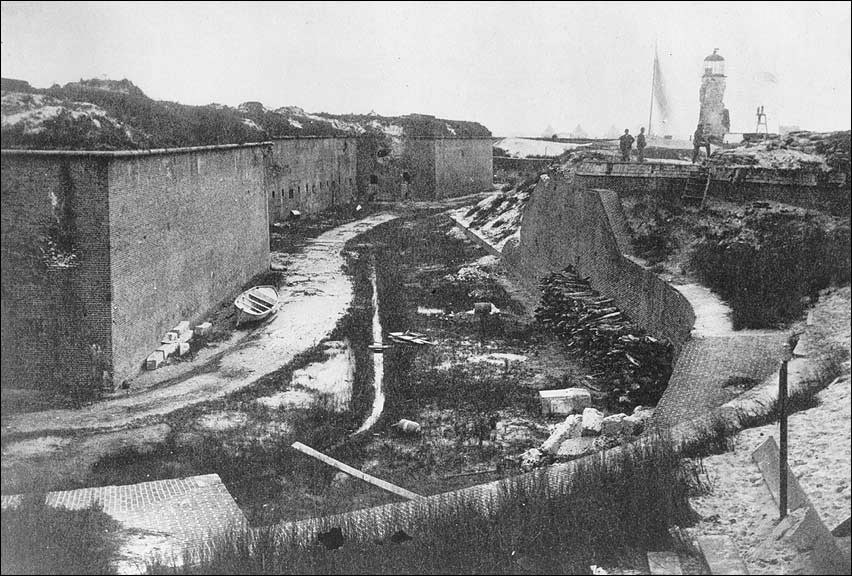

5) Two photos of the damage to Fort Morgan after the battle.

Visiting the site

Fort Morgan is a State Historic Site located 22 miles west of Gulf Shores, Alabama, at the end of State Highway 180. Museum exhibits tell the story of the fort's history. IFor more information, write the Superintendent, Fort Morgan Historic Site, 51 Highway 180 West, Gulf Shores, Alabama, 36542.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Setting the Stage

Though the most famous battles of the Civil War occurred on land, from the beginning both sides recognized that control of the seas would be crucial. This was due to the agriculturally based Southern economy that relied on shipping to receive goods and supplies. Once the Civil War began, President Lincoln ordered a blockade of Southern ports. The South responded to the North's strategy by "blockade running," which became the only way the Confederate states could supply themselves with direly needed wares. Ships filled with goods--some for the war effort, others for Southern consumers--left Nassau, the Bahamas; Havana, Cuba; the West Indies; and Bermuda attempting to sneak by the Union Navy. However, the Union Navy succeeded in closing many harbors such as Mobile, Alabama, which was deep enough to accommodate large ships.

The U.S. Navy had to grow rapidly to perform its roles. Though in 1861 it consisted of just 42 warships, by 1865 it had grown to 675 vessels. The North converted ships originally designed for other functions, such as whalers and tugs, and built others from scratch, many of which adopted the latest technology. The most famous example of innovation was the ironclad or "monitor" ships, which were named after the first vessel of its kind. The USS Monitor and subsequent, similar warships were armored with iron plate that was supposed to make them hard to sink. Union warships gradually added other features, including steam engines and more powerful guns. To counteract the Union Navy, the Confederates introduced a new weapon, which they called a "torpedo." Torpedoes were cheap, easily produced underwater mines that could seriously damage or sink ironclad ships.

The Union's armored ships and the Confederate's torpedoes clashed in combat during the summer of 1864 at Mobile Bay in Alabama. In July, Admiral Farragut prepared to lead the Union Navy in an attack on Fort Morgan, which guarded the mouth of Mobile Bay. In the previous two years he had seized New Orleans and Galveston, and he was now ready to close the last major port still available to blockade runners on the Gulf of Mexico.

Locating the Site

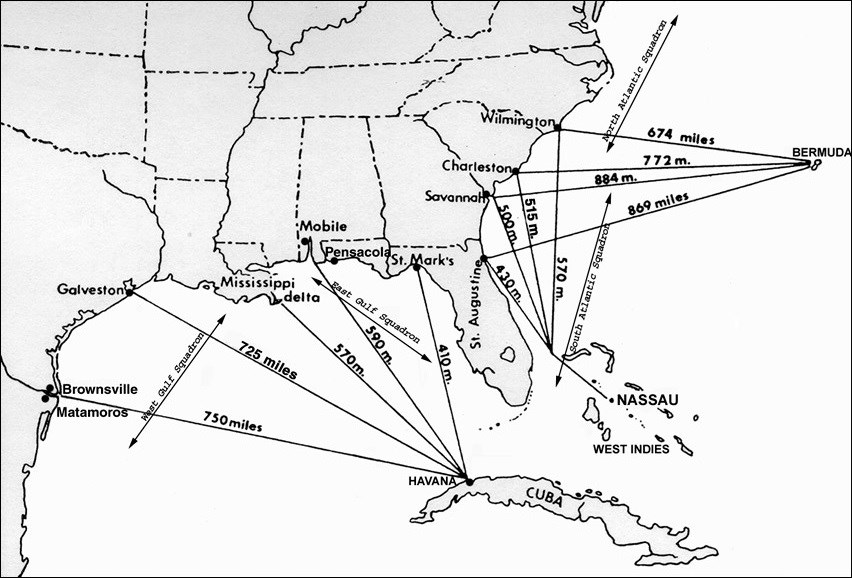

Map 1: The blockaded coasts.

The main starting points for blockade runners were Havana, Cuba; Nassau, Bahamas; the West Indies; and Bermuda. Many supplies also came via Matamoros to Brownsville, Texas, but transportation to needy areas (such as Richmond, VA) was limited because many small ports had no rail facilities.

Questions for Map 1

1. What ports would ships leaving Havana be most likely to head to?

2. What ports would ships leaving Nassau be most likely to head to?

3. What ports would ships leaving Bermuda be most likely to head to?

4. Note the location of the different Union squadrons. Why did they choose these particular locations? Considering the coastline they are attempting to block, describe why their task was so difficult.

5. If you commanded the Union Navy, which ports would you try to close first? Why?

Locating the Site

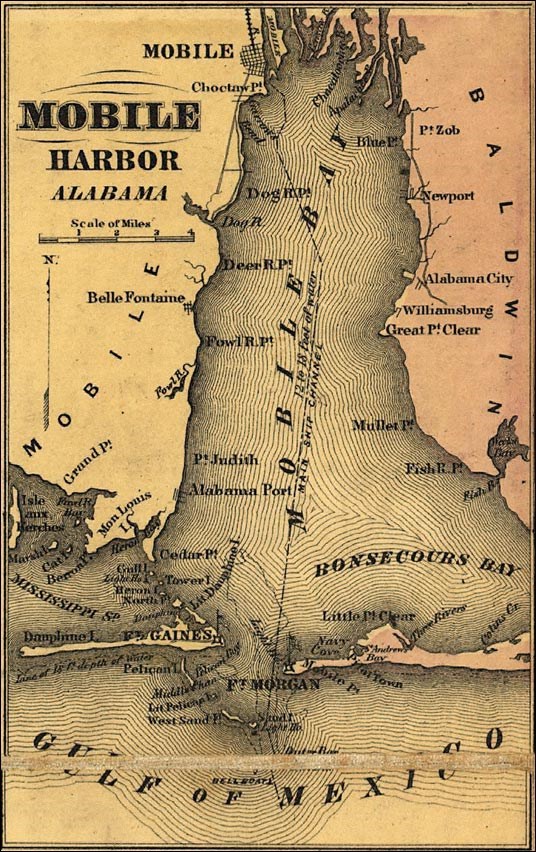

Map 2: Mobile Harbor and vicinity.

Library of Congress.

Map 1, taken from J. H. Colton's plans of U.S. Harbors, shows the position and vicinities of the most important fortifications on the sea-board and in the interior. The map was drawn from U.S. surveys and other authentic sources. Printed by Lang & Lang, New York, 1862.

Questions for Map 2

1. How far was Fort Morgan from the city of Mobile? Why do you think it was built where it was?

2. What besides Mobile Bay and the Gulf of Mexico would have made Mobile a transportation center?

3. What other defenses (both natural and man-made) guarded the bay? How risky was it for the Union Navy to attempt an entry into Mobile Bay?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Battle of Mobile Bay

The blockade was a crucial part of what the North called the "Anaconda Plan." As its name suggests, this strategy intended to squeeze the Confederacy until it surrendered. The Union Navy would cut off overseas trade by a tight blockade and divide the Confederacy in two by diving like a snake down the Mississippi River with a combined land and naval force. Together these two pressures would hopefully show the South that secession was futile and that it should surrender.

Blockade running became so important to the South that one historian called it "the lifeline of the Confederacy." Successful blockade-runners helped the South receive much-needed goods, while the ships' crews and owners received rich rewards to compensate for the risks taken. It was so vital to the Confederacy that while most of the vessels were privately owned at first, later in the war the state and Confederate governments became co- or full owners of the ships. However, the risks were great. If the Union captured a ship, it became Union property and its captain would spend the rest of the war in a Union prison.

The same limited industrial facilities that made the South need these ships meant it could only produce a limited number, which left the Confederates at a disadvantage on the seas. As the North worked hard to tighten its blockade, the South began to look to Europe for procuring not only ironclads to keep Union monitors from closing ports, but fast cruisers to keep trade flowing. British shipyards were building blockade-runners with more powerful engines; they also built what were known as commerce raiders, which attacked Union trading ships and took their goods. Yet pressures from the United States on these foreign countries limited the South's ability to secure the number of vessels needed for a successful blockade-running operation and for organizing a strong Confederate Navy.

The North continued to gain advantage as the war continued. By 1863, large blockade-runners could only operate in and out of Wilmington, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; Mobile, Alabama; and Galveston, Texas. Southern ocean trade dropped to one-third of its original level, and the Confederacy began running out of clothing, weapons, and other supplies.

In an attempt to counteract the Union Navy, especially the ironclads, the Confederates introduced the torpedo, which became very controversial. Before the Civil War, explosive devices had been floated towards enemy ships, but these could be seen on the surface allowing time for reaction. Torpedoes, on the other hand, remained hidden below the water, which provoked complaints from the North that no civilized country would use an "invisible" weapon. Union Adm. David Farragut explained the dilemma the North found itself facing: "Torpedoes are not so agreeable when used on both sides; therefore, I have reluctantly brought myself to it. I have always deemed it unworthy [of] a chivalrous nation, but it does not do to give your enemy such a decided superiority over you."¹

All of these issues converged at the Battle of Mobile Bay, which began on August 5, 1864 when Admiral Farragut's fleet moved into the torpedo-filled Mobile Bay. The fleet included 14 wooden ships (including the flagship Hartford), four monitors (the Tecumseh, Manhattan, Winnebago, and Chickasaw), as well as several gunboats that stayed nearby if needed. As the fleet neared Fort Morgan, the Tecumseh hit a torpedo and quickly sunk.

This loss did not stop the Union attack. Seeing what was happening, Admiral Farragut ordered his fleet to press forward through the underwater minefield into Mobile Bay. The 13 other ships made it past Fort Morgan, then, after some resistance, forced the Confederate ships in the bay to surrender or flee. Over the next three weeks, fire from Farragut's vessels and the Union Army finally forced the defenders of Fort Morgan to surrender. Though the city of Mobile would remain in Confederate hands into 1865, the port was now closed to blockade runners.

This victory brought a tremendous boost to Northern spirits, but at a high cost. Monitors were widely believed to be unsinkable--yet it took the Tecumseh just two minutes to go down. In the end, only 21 of the 114 men aboard escaped death. In addition, while clearing the many torpedoes, seven more Union ships, including two ironclads, sank. Their loss provided a particularly painful illustration of how changing technology affects the men fighting a war.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why was it important for the Union Navy to close the port of Mobile?

2. Why did captains and ship owners run the blockade? What risks did they face?

3. What technological advantage did the North think they had over the South in the Battle of Mobile Bay?

4. What new pieces of technology did the South use in the Battle of Mobile Bay?

5. Admiral Farragut said that "chivalrous nations" would not use a weapon like the torpedo. Why did he say that? How can some weapons be more civilized than others?

6. What did both Confederate and Union soldiers discover about ironclad ships?

7. If the city of Mobile remained in Confederate hands, why did the North consider this battle a victory?

Reading 1 was compiled from Arthur W. Bergeron, Jr., Confederate Mobile (University Press of Mississippi, 1991); E. Merton Coulter, The Confederate States of America 1861-1865: A History of the South, vol. VII (Louisiana State University Press, 1950); John Coddington Kinney, First Lieutenant, 13th Connecticut Infantry, and Acting Signal Officer, U.S.A., "Farragut at Mobile Bay," in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: Retreat with Honor, vol. IV (Castle Books, a division of Books Sales, Inc., 114 Northfield Ave., Edison, NJ 08837); Blanche Higgins Schroer, "Fort Morgan" (Baldwin County, Alabama) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975; Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988).

¹John Coddington Kinney, 380.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The Defense of Fort Morgan: The Report of Brig. Gen. Richard L. Page, Commander of the Fort

Early on the morning of the 5th of August, 1864, I observed unusual activity in the Federal fleet off Mobile Bay, indicating, as I supposed, that they were about to attempt the passage of the fort. After an early breakfast the men were sent to the guns. Everybody was in high spirits. In a short time preparations were ended, and then followed perfect silence, before the noise of battle.

At 6 o'clock A.M. the enemy's ships began to move in with flags flying. They gradually fell into a line, consisting of twenty-three vessels, four of which were monitors. Each of the first four of the largest wooden ships had a smaller one lashed on the side opposite the fort, and was itself protected by a monitor between it and the fort. The smaller ships followed in line.

As they approached with a moderate wind and on the flood tide, I fired the first gun at long range, and soon the firing became general, our fire being briskly returned by the enemy. For a short time the smoke was so dense that the vessels could not be distinguished, but still the firing was incessant.

When abreast of the fort the leading monitor, the Tecumseh, suddenly sank. Four of the crew swam ashore and a few others were picked up by a boat from the enemy. Cheers from the garrison now rang out, which were checked at once, and the order was passed to sink the admiral's ship and then cheer.

At this moment the Brooklyn, the leading ship, stopped her engine, apparently in doubt; whereupon the order was passed to concentrate on her, in the hope of sinking her, my belief being that it was the admiral's ship, the Hartford. As I learned afterward, he was on the second ship. Farragut's coolness and quick perception saved the fleet from great disaster and probably from destruction. While the Brooklyn hesitated, the admiral put his helm to starboard, sheered outside the Brooklyn, and took the lead, the rest following, thus saving the fouling and entanglement of the vessels and the danger of being sunk under my guns. When, after the fight, the Brooklyn was sent to Boston for repairs, she was found to have been struck over seventy times in her hull and masts, as was shown by a drawing that was sent me while I was a prisoner of war at Fort Lafayette.

The ships continued passing rapidly by, no single vessel being under fire more than a few moments. Shot after shot was seen to strike, and shells to explode, on or about the vessels, but their sides being heavily protected by chain cables, hung along the sides and abreast the engines, no vital blow could be inflicted, particularly as the armament of the fort consisted of guns inadequate in caliber and numbers for effective service against a powerful fleet in rapid motion. The torpedoes in the channel were also harmless; owing to the depth of the water, the strong tides, and the imperfect moorings none exploded....

Questions for Reading 2

1. How did the Union Navy take advantage of the natural conditions in their attack?

2. How did Farragut's brave and clever action in passing the Brooklyn save the Union's fleet?

3. All the Federal accounts agree that the USS Tecumseh was sunk by a torpedo, yet Brigadier General Page stated that the torpedoes were harmless. He never gives an alternative explanation for its fate, however. From the rest of his account, how do you think he would have accounted for the sinking? Why do you think he was vague?

Reading 2 was excerpted from Brigadier-General R. L. Page, C.S.A., Commander of the Fort, "The Defense of Fort Morgan," in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: Retreat with Honor, vol. IV (Castle Books, a division of Books Sales, Inc., 114 Northfield Ave., Edison, NJ 08837), 408-410. This account was not published until the 1880s, but it closely follows Page's original report written the day after the battle.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Personal Account of the Battle of Mobile Bay by Harrie Webster, Third Assistant Engineer, USS Manhattan

About half past seven, while the action was at its height, our gun had just been revolved for a shot at Fort Morgan, a momentary view was had of the Tecumseh, and in that instant occurred the catastrophe whereby a good ship filled with men, with a brave captain, in the twinkling of an eye vanished from the field of battle.

A tiny white comber [a long curling wave] of froth curled around her bow, a tremendous shock ran through our ship as though we had struck a rock, and as rapidly as these words flow from my pen the Tecumseh reeled a little to starboard, her bows settled beneath the surface, and while we looked her stern lifted high in the air with the propeller still revolving, and the ship pitched out of sight like an arrow twanged from the bow. We were steaming slowly ahead when this tragedy occurred and, being close aboard of the ill-fated craft, we were in imminent danger of running foul of her as she sank. "Back hard" was the order shouted below to the engine room, and, as the Manhattan felt the effects of the reversed propeller, the bubbling water round our bows, and the huge swirls on either hand, told us that we were passing directly over the struggling wretches fighting with death in the Tecumseh.

The effect on our men was in some cases terrible. One of the firemen was crazed by the incident. But the battle was not yet over. After coming to a standstill for a few minutes, during which the commotion of the water set up by the foundered ship passed away, the Manhattan steamed ahead into line and took the duty by now being performed by her lost consort. As the Tecumseh sank to the bottom, the crew of the Hartford sprang to her starboard rail and gave three ringing cheers in defiance of the enemy and in honor of the dying.

Perhaps some drowning wretch on the Tecumseh took that cheer in his ears as he sank to a hero's grave, and we may imagine the sound as it pierced the roar of battle, giving courage to some fainting heart as his face turned for the last time to the light of that sun whose rising and setting was at an end for him.

But Mobile Bay was yet before us. Immediately following the events just related, my tour of duty in the turret ended for the time being, and I once more returned to the engine room. The first effect of going from the cool air of the turret to the terrible heat of the engine room was that of a curious chilliness. This, in a minute or two, was succeeded by a most copious perspiration, so violent that one's clothing became soaking wet, and the perspiration coursing down the scantily clothed body and limbs, filled the shoes so that they "chuckled" as one walked.

At 150 F. the glass in a lantern will crackle and break, the lamps burn dimly, and it is impossible to handle any metal with the bare hands. Pieces of canvas, like flat-iron holders [flat irons were heated on a hot stove and then used to press or iron clothing; holders were similar to hot pads] alone enable one to grasp a hand-rail or valve handle. Of course frequent bulletins of the fight were brought to the poor devils sweating their lives out in the engine room, and we got some idea of what was going on through the signal which at frequent intervals came from the pilot house.... The sounds produced by a shot striking our turret were far different from what I had anticipated. The scream of the shot would arrive at about the same time with the projectile, with far from a severe thud, and then the air would be filled with that peculiar shrill singing sound of violently broken glass, or perhaps more like the noise made by flinging a nail violently through the air. The shock of discharge of our own guns was especially hard on the ears of those in the turret, and it seemed at times as though the tympanums must give way.... At about eight o'clock the fire on our port hand began to slacken, and the word was passed below that the wooden fleet had entered the bay and that the fight was over.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Is it clear from Webster's account why the USS Tecumseh sank? Why would a torpedo make the ships sudden sinking seem so mysterious? Would a torpedo, or cannon fire, from Fort Morgan cause more immediate and lethal damage? Why?

2. How did Webster and his mates respond to the sinking? Why do you think the crew of the Hartford gave three cheers for the fallen mates aboard the USS Tecumseh? How does Webster's account reveal the camaraderie that develops among a ships' crew in time of war?

3. Beginning with the sentence, "But Mobile Bay was yet before us," underline passages that give clues to the hardships of serving on board a monitor. How did the new technology of the monitors create additional hardships? What was Webster's impression of the battle from below board? How might that differ from the impression of the battle by a defender at Fort Morgan?

4. Explain how first-hand accounts help people appreciate the hardships battles place on individuals.

Reading 3 was excerpted from Harrie Webster, "An August Morning with Farragut at Mobile Bay," in Civil War Naval Chronology: 1861-1865 (Compiled by Naval History Division, Navy Department, Washington: 1971), VI-94-95.

Visual Evidence

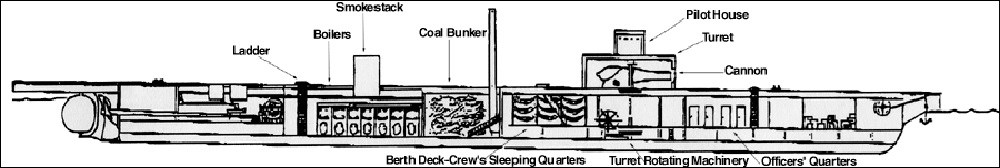

Drawing 1: Ironclad monitor.

(Fort Morgan State Historic Site)

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph #: NH 59543)

Questions for Drawing 1 & Painting 1

1. What features of a monitor rode above the waterline? How would that be an advantage in combat? How would it be a disadvantage?

2. In Painting 1, notice the wooden warship in the background. Note the differences between the wooden ship and the monitor. Which ship do you think would be more effective in battle? Why? On which ship would you rather have served?

3. Where were the living quarters in the monitor? What do you think it would have been like to live there?

4. Where were the working areas in the monitor? What do you think it would have been like to work there?

5. Do these images give you a better idea what it was like for Harrie Webster aboard the USS Manhattan in Reading 3? If so, how?

Visual Evidence

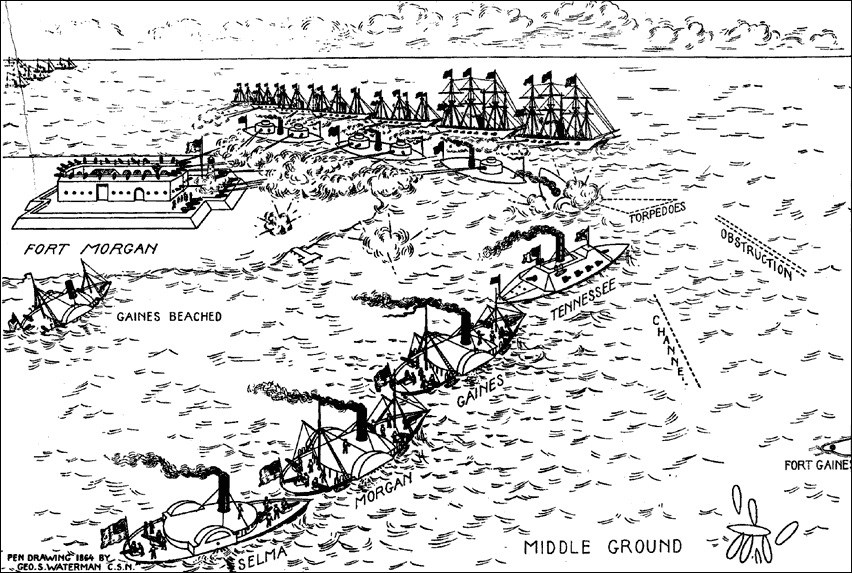

Drawing 2: Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864.

(Civil War Naval Chronology 1861-1865, p. VI-81)

Drawing 2 is a pen drawing done in 1864 by George S. Waterman, a Confederate sailor present at Mobile Bay.

Questions for Drawing 2

1. What obstacles did the U.S. Navy face upon entering Mobile Harbor? Does the objective of taking this port look like an easy task? Why or why not?

2. What advantages did the U.S. Navy have?

3. What advantages did the Confederates have?

4. Based on the drawing, which navy seemed most likely to win this battle? Why? Which navy won the battle? Why?

5. Why do you think the forts were not an effective defense during the Battle of Mobile Bay? If needed, refer to Reading 2 for your answer.

6. Based on what you know about the artist and the battle from the readings, how accurately do you think he portrayed the Battle of Mobile Bay?

7. Is it important to have first-hand accounts to understand what happened in historical events? Why or why not?

8. What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of first-hand accounts in understanding history?

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Plan of the battle of August 5, 1864.

(Library of Congress, Harper's Weekly, v. 8, Sept. 24, 1864, p. 613)

Wooden Vessels:

1. Brooklyn

2. Octorora

3. Hartford

4. Metacomet

5. Richmond

6. Port Royal

7. Lackawanna

8. Seminole

9. Monongahela

10. Kennebec

11. Ossipee

12. Itasca

13. Oneida

14. Galena

Iron-clads:

A. Tecumseh, sunk by torpedo

B. Manhattan

C. Winnebago

D. Chickasaw

E. Course of Union Fleet.

Rebel Vessels:

F. Ram Tennessee

G. Morgan

H. Gaines

I. Selma

Actions Taken:

J. Course of Ram.

K. Retreat of Rebel Wooden Vessels.

L. Morgan and Gaine's course toward Fort Morgan.

M. Hartford turning out for Brooklyn to back.

N. Course taken by Ram during second attack.

O. Ram surrendered.

P. Selma surrendered to Metacomet.

Q. Formed line; read prayers.

R. Union Fleet anchored.

Questions for Illustration 1

1. Find the location where the Union Fleet anchored after the Battle of Mobile Bay. Why did the Union Navy want to close down the port of Mobile? Why do you think this would be the best place to anchor the fleet after the victory?

2. The Confederate vessels were greatly outnumbered by the Union Navy. The few ironclad ships the Confederate navy acquired were called "rams" instead of "monitors." Find the lone ram of the Confederate Navy's fleet that participated in the Battle of Mobile Bay. Follow its course and describe why this ship's route was so perilous.

3. Compare and contrast Illustration 1 to Drawing 2. Are there any differences in the way the battle was depicted? If so, what are they?

4. Which visual, Illustration 1 or Drawing 2, would you consider to be a more accurate portrayal of the battle? Why?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: The gulf side of Fort Morgan, after the Battle of Mobile Bay.

National Archives.

National Archives

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Examine Photo 1 closely. Why would the designers of the fort have created openings for the guns (called "embrasures") in the main earthwork, rather than placing all the guns on top of the wall?

2. What evidence of damage can you detect in Photos 1 & 2? How do you think this destruction affected the morale of the garrison?

3. What does the damage noted in Photos 1 & 2 tell you about the effectiveness of pre-Civil War masonry fortifications against large caliber naval cannons?

Putting It All Together

The following activities help students better understand reactions to new technologies and the role of military installations in their own communities.

Activity 1: Decisions in Warfare

Ask your students to think about the actions of Admiral Farragut. Against all odds, he forged ahead into Mobile Bay even after losing a monitor which was thought to be "unsinkable." He ordered his fleet into perilous waters filled with torpedoes and obstructions. Have them write a paragraph that considers the balance between risk and recklessness, between courage and foolheartedness. Have them discuss their individual viewpoints with their classmates.

Activity 2: The Perils of New Military Technology

Assign students a short research paper on an advance in military technology that was controversial when first used. Submarines, flame-throwers, hand grenades, poison gas, biological weapons, and atomic bombs are examples. Make one of their objectives determining when the weapon was developed, why, and public response to its use. Students also should address the question, "Why were some weapons, submarines for example, eventually accepted while others, such as poison gas, are still considered uncivilized?"

Activity 3: Building a Fort

Divide students into small groups and ask each group to research a military installation that existed in their region. These installations might be defensive fortifications, supply depots, training facilities, or National Guard Armories. Groups should attempt to answer the following questions as they conduct their research:

-

Why was the installation located there? What was its purpose?

-

What was the most appropriate defense for protecting the installation?

-

How does its location help or hinder its defense?

-

What kind of weaponry was available to defend it? How many troops were required to defend it?

-

Did the installation fulfill its purpose? Was it ever breached by an enemy or abandoned by its original occupants?

-

How was the installation similar to or different from Fort Morgan?

Each group should take what they’ve learned to develop a poster that outlines the history and purpose of their installation. Hold a poster session for your students so they can have a chance to learn about the installations their classmates studied.

Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay, students will follow Admiral Farragut's attack on Fort Morgan and Mobile Bay, and consider the human reaction to technologies such as ironclads and underwater mines. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Civil War Resources:

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress created a selected Civil War photographic history in their "American Memory" collection. Included on the site is a photographic timeline of the Civil War covering major events for each year of the war.

The Valley of the Shadow

For a valuable resource on the Civil War, visit the University of Virginia's Valley of the Shadow Project. The site offers a unique perspective of two communities, one Northern and one Southern, and their experiences during the American Civil War. Students can explore primary sources such as newspapers, letters, diaries, photographs, maps, military records, and much more.

Battle of Mobile Bay Resources:

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile, Alabama: Discover 300 years of America is a Web site provided by the Mobile Convention & Visitors Corporation. Included is a "history and culture link" that gives a timeline of the historical events that occurred in Mobile, Alabama. Included are passages on its early explorers, Mobile during British Colonial times, Mobile after it was sieged by the Spanish, Mobile during the American Revolution, and Mobile before and during the Civil War.

Maritime Heritage Program

The National Park Service's Maritime Heritage Program works to advance awareness and understanding of the role of maritime affairs in the history of the United States by helping to interpret and preserve our maritime heritage. The program's Web pages include information on National Park Service maritime parks, historic ships, lighthouses, and life saving stations.