Profile in Preservation

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Washington

QUICK FACTS

Place of Birth: Prince George's County, Maryland

Date of Birth: Unknown, c. 1820-1830

Place of Death: Washington, DC

Date of Death: 1917

Associated Landscape: Fort Stevens Park, Washington, DC

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

Elizabeth Proctor Thomas was born in Prince George’s County, Maryland in the early 1800s. As a child, Thomas and her parents moved to Vinegar Hill, a small community of free blacks located in northwest Washington, D.C., approximately two miles south of the Maryland border. The family settled on a high point beside the Seventh Street Turnpike, a major road leading to downtown Washington.

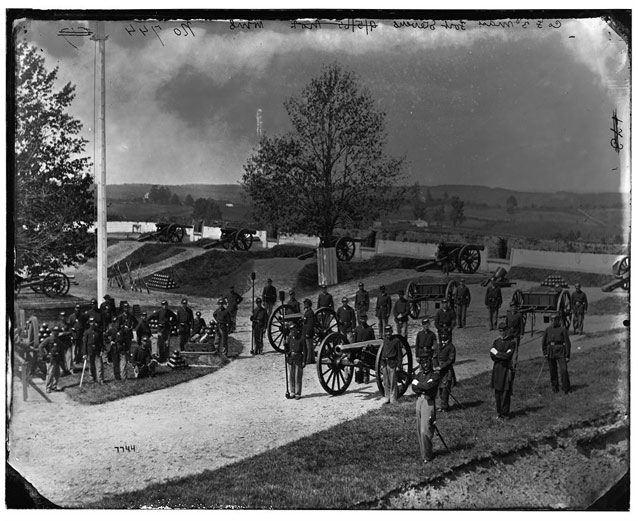

When the Civil War began, the nation’s capital was protected by a single fort: Fort Washington, located 12 miles south of the city along the Potomac River. Realizing the defense of the capital was dangerously inadequate following the Union defeat at Manassas in July 1861, Congress voted in favor of constructing a ring of forts and other defensive works to encircle the city. Soon afterwards, miles of trees were cleared and building commenced. By the end of the war, 68 forts, 93 batteries, 20 miles of rifle pits, and 32 miles of military roads surrounded the capital and Washington became the most heavily fortified city in the world.

William Morris Smith, from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The Thomas’ Seventh Street Turnpike property, then owned by Elizabeth and her siblings, was an ideal and necessary location for a fort. In September 1861, Union troops took possession of her land and ultimately destroyed her home, barn, orchard and garden to build Fort Massachusetts, later renamed Fort Stevens. According to Thomas, at the time her house was being demolished she was holding her six-month old baby and weeping beneath a sycamore tree. As soldiers removed her belongings, a tall, slender man dressed in black approached her and said, “It is hard, but you shall reap a great reward.” The man offering comfort was believed to be President Lincoln. Thomas’ encounter with the stranger was a story she told throughout her life, helping her story to gain recognition as part of the history of Fort Stevens.

In July 1864, Confederate troops under the leadership of General Jubal Early attempted to invade Washington. Fort Stevens and nearby Fort DeRussy led the defense of the capital as skirmishes broke out. President Lincoln, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, and members of the president’s cabinet traveled to Fort Stevens to observe the two-day battle. The president watched the fighting as Confederate sharpshooters fired upon the fort. President Lincoln became the second sitting president to come under enemy fire as Union forces successfully thwarted the invasion.

Courtesy of The Historical Society of Washington

Following the Civil War, Elizabeth Thomas continued to reside near Fort Stevens. She remained the owner of portions of the fort, and during the course of her life, she amassed a considerable amount of land in the vicinity. At the turn of the century, Thomas sold some of her Fort Stevens acreage to an influential Washingtonian who hoped to preserve the remaining earthworks and establish a park.

In 1911, she joined veterans of the Battle of Fort Stevens for the dedication of a monument to President Lincoln located on the site where he observed the 1864 conflict. For many years, Elizabeth Thomas fought for compensation for the damage and loss of her property incurred during the war. She was eventually awarded $1,835 in 1916, a year before she died.

NPS Photo

During the 1920s, the federal government acquired Fort Stevens and the site became a unit of the National Park Service in the 1930s. During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps reconstructed a portion of the fort. Today, Fort Stevens is a neighborhood gathering place where the stories of the battle and Elizabeth Thomas continue to be told.

LANDSCAPE SKETCH

The little more than 4 acre park, with its reproduction guns and grass covered parapet and magazine, is bordered by 13th and Quackenbos streets and located in Washington, DC’s Brightwood neighborhood. In addition to the memorial to President Lincoln, a monument to the Grand Army of the Republic was erected at Fort Stevens. Dedicated in 1936 by the Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War, the memorial is a bronze bas-relief model of the fort mounted on a mosaic concrete base designed by John J. Earley. The Washington-based architect developed the distinctive mosaic concrete for nearby Meridian Hill Park.

Carol Highsmith, from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Last updated: October 15, 2021