Profile in Preservation

Photo courtesy The Monuments Men Foundation website

Amidst the cultural and political unrest of World War II, individuals working for what was called The Roberts Commission extended personal passions for art, design, history, architecture, and education into a much broader public sphere. In doing so, they played an essential role in preserving treasured cultural resources from the destructive threat of war.

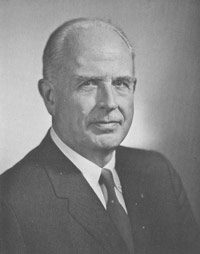

One of the individuals serving on The Roberts Commission was Lt. Col. Norman Thomas Newton. Newton served as director of the sub-commission known as the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Section of the Civil Affairs Division from 1942 to 1943 and continued as an attachment to the British Eighth Army in Italy until 1946. This section was referred to as the “Monuments Men,” although the group of nearly 350 contained both men and women.

The multi-national collection of museum curators, architects, artists, and academics identified and re-located millions of cultural and artistic materials that had been seized by the Nazis. As a landscape architect, Newton’s role involved surveying the condition of cultural sites and monuments, as well as formulating recommendations for their conservation. His wartime efforts earned him several awards and honors from the Italian government.

The Earlier Years: Designed Gardens, Public Works, and the National Park Service

Norman Newton’s influence in areas of landscape architecture and conservation was not limited to his WWII involvement. Newton earned a master’s degree in landscape design from Cornell University in 1920. He was documenting the Italian landscape well before the war years, when he spent three years studying the gardens of Italian villas in Rome as a Fellow of the American Academy. During that period, he produced a meticulous and expansive collection of drawings, and he also explored other disciplines as a means to enhance his relationship to landscape design.

Courtesy of Cornell University Library via Flickr

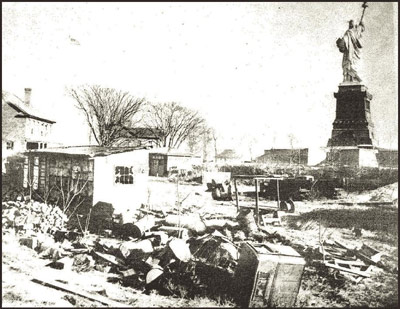

NPS, Statue of Liberty National Monument

Returning to the United States in the late 1920s, Newton entered private practice for several years and designed gardens for country estates. He was becoming increasingly involved with public works projects, such as those administered by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

Between 1933 and 1939, he was appointed associate landscape architect for what is now the Northeast Region of the National Park Service (NPS). One of his most notable projects was the creation of a master plan for Bedloe’s Island (now Liberty Island), the site of the Statue of Liberty in New York City. His design plan called for removal of old army barracks and the addition of a formal design of lawns, plantings, and walkways.

Other public projects with the NPS included master plans for the Custom House at Salem Maritime National Historic Site and Saratoga Battlefield National History Park in New York.

Newton’s Landscape Architecture in Context

Norman Newton’s approach to landscape architecture was a reflection of personal and cultural contexts, demonstrating a thoughtful convergence of ordered design, public works, and conservation planning.

NPS Photo, Statue of Liberty National Monument

The 1930s was a period of reorganization, diversification, and development in the NPS. Against the societal backdrop of the Great Depression, New Deal programs provided funding and personnel to the NPS for park development projects. These emergency conservation projects supported the federal conservation needs of the country’s popular national parks and monuments, while also helping to stimulate the weakened economy.

Newton entered the NPS in the midst of this period of change, and his own commitments to public works projects and conservation echo the developing aims of the agency.

After the war, Newton returned to the United States as a faculty member of the Harvard Graduate School of Design and member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, where he continued to influence the field as a critic, author, and educator. Newton’s most notable works include War Damage to Monuments and Fine Arts of Italy, documenting his experience as a Monuments Man; and Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture (1971), which continues to be recognized as a core educational text of the discipline.

In Design on the Land, Newton connects landscape architecture and conservation, emphasizing that both require a “desirable optimum relation between the piece of land and the proposed use: in short, wise use of the land.” He applied this ethic across private spaces, national parks, and historic landscapes threatened by war, uniting landscape architecture and conservation in a way that extends beyond the immediate use of the land. From the Statue of Liberty to the statues of Ancient Rome, Newton demonstrated how well-ordered design can guide viewers to a fuller appreciation of history and the associated landscape.

After Newton: The Movie, the Legacy, and the Future

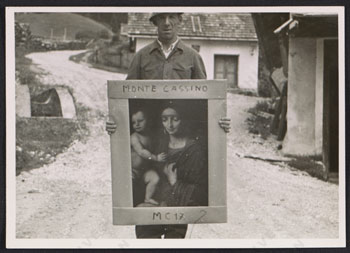

Part of the Thomas Carr Howe papers, Courtesy of Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The 2014 release of the major motion picture The Monuments Men throws new light upon this intriguing ancillary activity of World War II. Officially titled the “American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas,” or “The Roberts Commission” after its chairman Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts, the effort represents unified interests of civilian and military divisions.

Robert Edsel, co-author of the book The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History that inspired the movie version, stated in a February 2014 interview with The Washington Post, “If there’s an overarching message of the Monuments Men and Women, it is that shared sense of civilization, that these great creative achievements of mankind belong to everybody and should be preserved, even at the risk of their own lives.” Just as Newton’s landscape architecure work with the NPS and the MFAA demonstrates that structure and boundaries can expose a better understanding of the landscape and its history, the frames of this movie present and preserve a remarkable story of conservation in the face of crisis.

National Archives and Records Administration.

If the experience and the story of the designed landscape is a shared one, as Edsel points out, so too becomes the responsibility to maintain the value of these spaces.

Last updated: August 16, 2017