How an American President's Leadership Unites the Allies

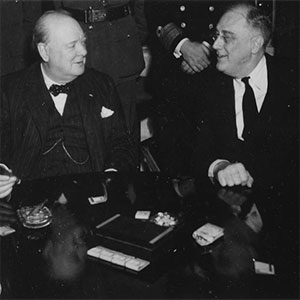

FDR Library

June 1940. Britain and its new prime minister, Winston Churchill, stood alone as the last bastion against the Nazis and their domination of Europe. World War II had begun on September 1, 1939. In less than one year, the German war machine had engulfed Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, and France and was poised on the shores of the English Channel to invade Great Britain.

May 1940 witnessed the defeat of British and French forces by the Nazis at the Battle of Dunkirk. Despair and resignation about becoming yet another conquered nation began to spread among the people of Britain. Winston Churchill would have none of it. He raised the battle cry, giving one of the greatest speeches in history on June 4 in an effort to rally British spirits. He said, “Even though large tracts of Europe…have fallen or may fall into…all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end...we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be…” At the conclusion of the speech, he reportedly said to a colleague, “And we’ll fight them with the butt ends of broken beer bottles because that’s bloody well all we’ve got.” The German Luftwaffe air force began to rain bombs on London and nearby areas, hoping to force a quick surrender. British ships were being sunk regularly on the Atlantic Ocean.

As Britain stood alone, Churchill knew that the only hope for the nation’s survival and the rest of Europe lay in the hands of the president of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR).

By 1940, FDR had been president for two terms. Historically, no other person who held that office had served for more than eight years. FDR was giving serious thought to running for an unprecedented third term mainly because of the events unfolding in Europe as well as in the Pacific, since the Japanese government had signed a pact with Germany and Italy. The relationship between the United States and Japan had grown tense after the Japanese began military aggression against China in 1938. The Japanese government had their eye on dominating the Chinese mainland and the Pacific Islands.

Living through World War I and the events leading up to it, FDR felt that US involvement in the current conflict was inevitable. It was just a matter of time. He wanted to be the commander-in-chief of the country when that occurred. While the British and Churchill were battling the Nazis over 3,000 miles away, across the Atlantic Ocean, FDR was fighting against the forces of isolationism that were gripping the American people. When FDR made the decision to run for the presidency in 1940, he promised the American people that the country would be kept out of war. He made no promises to Winston Churchill. Churchill wrote to FDR, after the November election, “…I prayed for your success…We are entering a somber phase of what must inevitably be a protracted and broadening war…” FDR gave no response. But he subtly engaged in preparing the American people for the possibility of future entrance into the conflict.

Less than two months after the presidential election, FDR addressed the American people through one of his radio fireside chats. It became known as his "Arsenal of Democracy" speech. He began by saying, “This is not a fireside chat on war. It is a talk about national security....If Great Britain goes down, the Axis powers will be in a position to bring enormous military and naval resources against this hemisphere.” Knowing that Americans were opposed to getting involved in the war, he focused on the importance of assisting the British, who were doing the fighting and keeping the Nazi threat away from our shores. FDR said, “We are the Arsenal of Democracy. Our national policy is to keep war away from this country.” The implication was that the best way to accomplish this was to send military aid to the country that was keeping the enemy at bay.

Beginning in March 1941, massive amounts of military supplies, including ships and planes, were given to Great Britain under FDR’s Lend-Lease program. Nine months later, on December 7, 1941, Japanese war planes attacked the American fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The United States immediately declared war; at that point, Winston Churchill and the British people were convinced the world would now be saved.

During the course of the war, FDR and Churchill met on several occasions to plan war strategy. The British prime minister visited the United States four times between 1941 and 1944. Some of these meetings were at FDR’s home in Hyde Park. Arguably, the most historically significant of these was held in the study at President Roosevelt’s home on September 14, 1944. In that small room, FDR and Churchill initialed a document called the Hyde Park Aide Memoire that outlined the collaboration between the United States and Great Britain in the development of an atomic bomb, then called Tube Alloys and later known as the Manhattan Project. In the document, it was stated that this project would be kept secret, especially from the Russians, and included the possibility of using the bomb against the Japanese.

When FDR died in office on April 12, 1945, Winston Churchill wrote, “It is cruel that he will not see the Victory which he did so much to achieve.” The war in Europe ended in May of that year. The war with Japan concluded in August after FDR’s successor, President Harry Truman, decided to use the atomic bomb against the Japanese to help shorten the war.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill forged a bond that surmounted what seemed an unsurmountable enemy and saved the world. In his eulogy to the president, the British prime minister said, "In FDR there died the greatest American friend we have ever known.”

Last updated: November 17, 2015