Last updated: May 7, 2020

Article

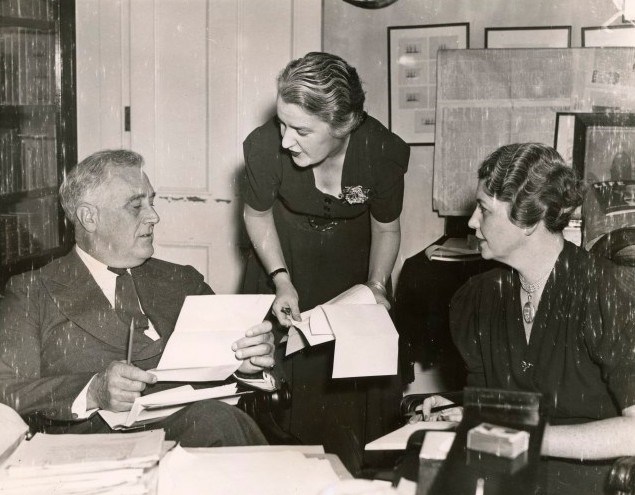

FDR's Office at Springwood

Photo Courtesy FDR Library

Like most presidential homes, Springwood functioned as a "little White House," but it retained the sense of informality, rest, and relaxation it had always had for Franklin D. Roosevelt. When he returned to his childhood home the morning after his election to be the next President of the United States, he greeted the cheering crowd gathered on the front lawn with the comment "I'll always be plain Franklin Roosevelt in this part of the country, and don't forget that."

FDR was away from Washington far more often and for longer periods of time than any of his predecessors, often returning to either New York or Georgia when he wasn't traveling in an official capacity. While he was in residence in Hyde Park, FDR participated in community life; welcomed dignitaries, supporters, and the media; and conducted the work of the presidency. As he had done since the early years of his public career, he invited national political figures to lunch, tea, or dinner at Springwood, usually with reporters present. One of a very small number of known photographs that show FDR in his wheelchair was taken in September 1937 on the terrace at Springwood, illustrating the relative freedom he felt there to drop some of his public persona.

FDR returned to Hyde Park 137 times during his 12 years in the Oval Office, continuing to seek both peace and inspiration from the place with which he was most familiar as he faced increasingly unfamiliar problems and responsibilities as President. During FDR's presidency, Cabinet members, heads of state, royalty, congressmen, senators, and Secret Service stayed at Springwood. Visitors met with FDR in his study and often shared a meal or two with the family and other guests who were on hand. Political leaders, such as Upton Sinclair, the Democratic candidate for governor of California in 1934, came to seek FDR's support or discuss campaign strategy. The president of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad and Joseph Patrick Kennedy visited the President the same day as part of FDR's efforts to work with big business. Labor leaders such as William Green, head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), who visited in 1936, came to discuss labor's role in FDR's political campaigns. On July 7, 1940, James Farley, the Democratic National Committee Chairman who skillfully directed FDR's 1932 and 1936 campaigns and aspired to succeed him as president, drove to Hyde Park to seek a commitment from FDR not to run again. However, FDR told Farley that if he received the nomination he could not refuse to accept it and subsequently defeated Wendell Willkie in the 1940 election, becoming the first American president to win election to a third term.

Sometimes Eleanor Roosevelt brought people to Hyde Park to share information or ideas that she thought FDR should hear. In 1933, she invited Dr. Alice Hamilton, a professor of public health at Harvard who had just returned from a ten-week fact-finding trip to Germany, to meet with FDR. Hamilton reported in detail about Hitler's treatment of his liberal and leftist opponents and his persecution of the Jews.

Photo Courtesy FDR Library

Following the United States' entrance into World War II in December 1941, as the pressures of leadership and the trauma of the war intensified, FDR spent even more of his time at Hyde Park. From December 7, 1941, to his death in 1945, he spent about 20 percent of his time here. After January 1942, he was at Hyde Park nearly every month. Wartime security measures allowed FDR to move about the country in reasonable secrecy, and he spent at least one or two weekends a month at Hyde Park. Key members of his personal staff, including his secretaries Marguerite "Missy" LeHand and Grace Tully, and his personal secretary William D. Hassett, always accompanied FDR. Although these visits were working holidays, FDR's correspondence during the war years referred often to the respite he received from them. In a February 1942 letter to Eleanor, he explained, "the one essential in wartime is complete lack of distraction on the very occasional weekend I can get away from Washington."

Even before entering the Oval Office, FDR laid the groundwork for his sweeping economic recovery program during various discussions and brainstorming sessions held in his study at Hyde Park. In August 1931, Samuel Rosenman, one of FDR's speechwriters, came to Springwood to work on a special message to the New York legislature on a relief program for the state. The message drafted that day led to the establishment of the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA), the boldest action that any governor had yet taken to combat the effects of the Depression and a model for the New Deal programs to come.

NPS Photo

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill arrived in Hyde Park on the morning of June 19, and FDR subsequently gave him a tour of the estate in his hand-controlled Ford, during which Churchill first broached the subject at hand. The following afternoon, the two men met in the president’s study at Springwood with only Harry Hopkins joining them. Churchill urged that the British and Americans "at once pool all our information, work together on equal terms, and share the results, if any, equally between us." FDR agreed with this proposal, with the United States taking full responsibility for the design, engineering, and production of the bomb in recognition of Britain's weak economic position. Churchill and Roosevelt again discussed the atomic bomb in Hyde Park after they attended the Second Quebec Conference in September 1944. At the high-level military conference, the men, along with Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, had reached agreement on the planned Allied occupation zones in Germany, continued U.S. economic aid to the United Kingdom, and British naval participation in the conflict against Japan. FDR subsequently entertained Churchill at Hyde Park for two days, a visit that resulted in a top-secret memorandum in which they agreed to continue to keep "Tube Alloys" a secret and to consider using it against the Japanese once it proved ready.

FDR was the first modem president to use media in a systematic way to promote his ideas and reach the public; consequently, all Americans became familiar with Springwood as his home. He held many press conferences in Hyde Park and delivered several Fireside Chats and radio addresses from his study. In his Fireside Chat delivered on April 28, 1935, the President offered an explanation to the public for the strong ties his home at Hyde Park continued to hold for him: "The most difficult place in the world to get a clear open perspective of the country as a whole is Washington…that is why I occasionally leave this scene of action for a few days to go fishing or back home to Hyde Park, so that I can have a change to think quietly about the country as a whole."