Last updated: August 9, 2025

Article

Fanny & Henry: A Romance

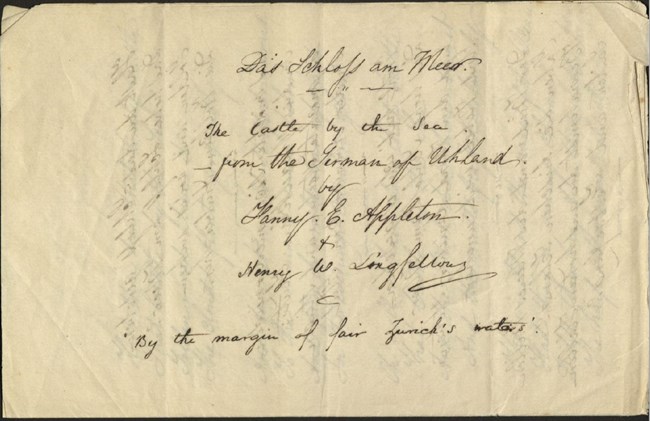

NPS Photos, LONG 544 & LONG 4437

Courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University, MS Am 1340 (71).

First Meeting

In July 1836, nineteen-year-old Fanny Appleton was in Thun, Switzerland in the middle of a Grand Tour with her family. They had left behind their Beacon Street home in Boston in the wake of two family tragedies: Fanny’s mother’s death in 1833 and her older brother’s death the month before they set sail.

Henry Longfellow was a college professor and published author, travelling abroad to improve his command of European languages in preparation for his new position as the Smith Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard University. He had tragically lost his first wife, Mary Storer Potter Longfellow, to complications following a miscarriage just nine months earlier.

That summer, Henry joined the Appleton family and they passed their days traveling the Swiss Alps – to Interlaken, Lucern, Zurich, and Schaffhausen – and going for boat rides, swims, walks, and sketching parties. Fanny and Henry spent their evenings engaged in conversation about poetry and art. Henry endeavored to teach Fanny German by translating the poetry of Ludwig Uhland, including “The Castle by the Sea.”

On August 2, Fanny wrote in her journal: “Have a nice walk in the P.M. with Mr. L to the old bridge, sketch the cloister-spires from a wall, . . . A nice talk – delicious twilight.

Still, grief followed them. Fanny’s cousin, William Appleton, was slowly dying of consumption during their travels. Fanny was distraught over his health and overwhelmed by her feelings. Henry, no stranger to loss, was sympathetic and went for long walks with Fanny as she grieved. Henry’s kindness and attention to William touched Fanny. On August 19, 1836, Henry left to return to the United States. Fanny wrote in her journal: “Miss Mr. L. considerably.” On August 24, William died. He was buried by his family in Schaffhausen, Switzerland.

"The Madness of Passion"

Henry returned to America in 1836 to take up his professorship at Harvard. Soon after settling in Cambridge, he found himself welcomed into the Beacon Hill parlor of Fanny’s aunt. At her encouraging, Henry sent a New Year’s Valentine to Fanny – it was another translation of Uhland’s German poetry.

Soon, Fanny was peppered with questions about her marital status and the “Professor.” Her aunt wondered in a letter if Fanny would be the “last rose of Summer left blooming alone, all its lovely companions” married and gone. This aunt had been impressed by Longfellow, claiming, that he was the perfect choice for a husband. Fanny remained aloof and unconvinced, feeling unprepared to contemplate marriage.

Upon her return, Henry actively pursued Fanny, sending books of his favorite poetry, more of his translations, and even a pair of Spanish castanets for a costume ball. If there were any written responses from Fanny after her return from Europe, none survived. Over a year had passed, and she didn’t share the same interest in Henry.

On January 6, 1838, Henry wrote to his friend, George Washington Greene:

My nature craves sympathy–not of friendship, but of Love... To tell you the whole truth–I saw in Switzerland and travelled with a fair lady–whom I now love passionately (strange, will this sound to your ears) and have loved her ever since I knew her. A glorious and beautiful being–young–and a woman not of talent but of genius!–indeed a most rare, sweet woman whose name is Fanny Appleton. You saw her at Greenough's studio. You cannot have forgotten her. Tall, with a pale face. Well, that pale face is my Fate. Horrible fate it is, too; for she lends no favorable ear to my passion and for my love gives me only friendship. Good friends we are–but she says she loves me not; and I have vowed to win her affection. Ah! my friend! you know not how this is interwoven into my soul....I shall win this lady, or I shall die.

By 1838, thought, their relationship began to sour. It seems that Henry made his feelings known to Fanny and she did not return them. Henry wrote to Mary Appleton, her sister, that he would always love Fanny as his own soul, but that when they were last together, “we left one another without understanding” each other. In 1839, he hinted that there might have been a refused proposal:

The lady says she will not! I say she shall! It is not pride, but the madness of passion. I visit her; some-times pass an evening alone with her. But not one word is ever spoken on a certain topic…. So we both stand eyeing each other like lions.

And then Henry sealed his fate with a grand gesture. Writing to his friend George Washington Greene in 1839, he said “I shall fire off a rocket, which I trust will make a commotion in that citadel. Perhaps the garrison will capitulate; -- perhaps the rocket may burst and kill me."

His “rocket” was the publication of Hyperion that same year, a thinly-veiled autobiographical romance about a young American who travels to Europe and meets a woman who ultimately refuses his marriage proposal. He pulled extensively from his journals and letters to write it and felt that his heart had been “put into the printing press and stamped onto the pages."

Fanny felt the book was “desultory, objectless, a thing of shreds and patches like the Author's mind." References to Longfellow disappear from Fanny’s correspondence over the next few years, perhaps willfully so. While Henry felt he had gained a great victory over his own demons, he had placed Fanny firmly in public notoriety, and possibly hurt her chances of establishing a close relationship with another suitor.

NPS Photo, LONG Collection, LONG 15208

"Cool as an East Wind"

The intervening years were ones of personal growth on the part of both Fanny and Henry. Fanny began to write about marriage as if it could be seen as a “prisonhouse.” A marriage like this, she feared, could clip one's wings. She resolved not to hope unnecessarily for a future that might never happen, and instead, worked on bettering herself. She and her closest friend, Emmeline Austin Wadsworth, decided to no longer “decry people on small grounds or unworthy grounds.” Perhaps she was referring to her past treatment of a certain professor?

For Henry’s part, he had finally given up hope of ever wooing Fanny, telling his close friend:

The brazen lips of Fate have said that ‘Time is past!’… For though I feel deeply what it is not to have gained the love of such a woman, -- I have long ceased to think of it; -- and remember it only, when I see that my elasticity is nigh gone, and my temples are as white as snow. Three of the best years of my life were melted down in that fiery crucible.

And strangely, in his defeat, he seemed to finally find some peace.

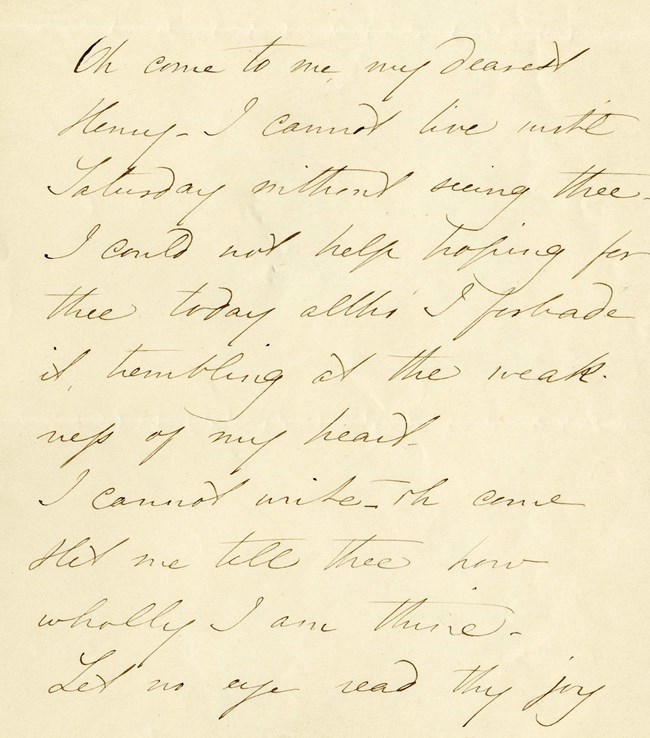

NPS Photo, Fanny Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow papers, LONG collections, 1011-2-1-13-3

"Written be the Date in Red Letters"

And then, abruptly, more than three years after Hyperion, the situation changed. On April 13, 1843, Fanny and Henry came face-to-face at the home of a mutual friend. Henry wrote in his journal, a year later, that this was the moment when they began to “draw near unto each other.” Over the next couple weeks, the two were quiet in their written references to each other. On May 10, Fanny sent Henry a letter: “oh come & let me tell thee how wholly I am thine."

It seems that Henry had proposed again, and this was her answer. During the following month, the couple sent letters to relatives, sharing their happy news. Those relatives, and indeed most of Boston society, must have been shocked by this change in affairs. In explanation to a friend, Fanny shared that her “heart has always been [made] of tenderer stuff than any body believed,” and that all it took was this engagement to set it flowing.

And so, on the evening of July 13, 1843, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Fanny Appleton gathered with a small group of family and close friends in the parlor at 39 Beacon Street, the Boston Common and the setting sun out their window, and were married. Fanny wore orange blossoms in her hair.

Fanny’s older brother, Tom, summarized the love story: “She is a nature that ripens late And she will be far happier than if she married earlier. With her to be understood and to understand is to love.”

Sources

Fanny Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow correspondence, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS collection.

The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Andrew Hilen, Vol. II.