Last updated: January 22, 2025

Article

Equality in Living History

Living History

Part of the National Park Service mission is to preserve special places and share their stories “for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” One of the tools that the NPS uses to do this is living history. Living history is a pre-planned demonstration of a skilled process using period reproduction equipment and clothing that educates visitors in an immersive way.In the 1980s, two legal challenges at Antietam National Battlefield were the catalyst for the entire NPS to confront and correct its role in inequitable treatment of those involved in living history. Below are their stories.

A Note on Terminology

Because of these two legal cases, current NPS policy now defines living history as a type of educational demonstration that does not attempt to re-create history. This “third-person” living history is standard practice at Antietam National Battlefield and many other national parks. The practice of depicting a specific historic individual, called “first-person” living history, is infrequently used.At the time of the events described (1981-1993), terminology and National Park Service guidelines were different. Demonstrations were presentations of a skilled process by modern individuals (regardless of dress) while costumed living history was often assumed to be a first-person depiction of specific individuals in an attempt to re-create history, often confused with re-enactment, especially in military and battlefield parks1.

Case 1: Historic Weapons Demonstration

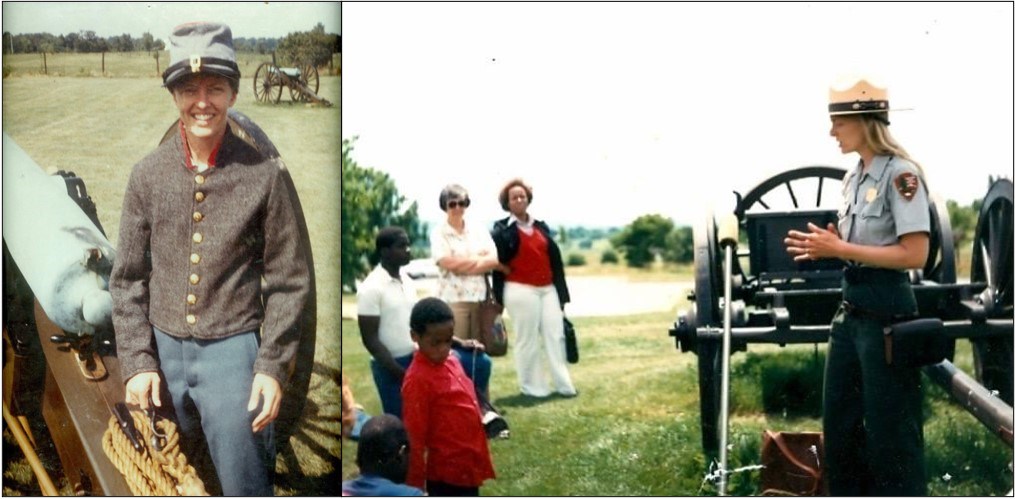

Pat Lammers began her career at Antietam in May 1980 as a seasonal Park Technician. Her duties included helping researchers and visitors, but the responsibility she enjoyed most was presenting third-person interpretive and historic weapons demonstrations to the public. She performed black powder rifle and cannon firing demonstrations and led programs about Civil War artillery and the role of women as soldiers and spies during the Civil War.

Photos courtesy of Pat Lammers.

A Complaint to the NPS Director

In 1981, the National Chairman of the Civil War Roundtable Association (CWRA) Jerry Russell, wrote a letter of complaint to NPS Director Russel Dickenson, about Lammers and other female interpreters performing artillery demonstrations at Antietam. (That year, most demonstrations were led by seasonal employees, all of them female. This was not uncommon at Antietam, where female employees had performed cannon and rifle demonstrations since the mid-1970s.2)

Russell’s complaint centered on his belief that women could not present first-person living history portraying soldiers. NPS Director Dickenson agreed and referring to guidance at that time wrote, “Living history demonstration [guidelines] clearly state that accuracy is mandatory in living history. The use of women in period military uniform violates that basic tenet.” Director Dickenson proposed to “use the ladies in NPS uniforms” during demonstrations and informed Russell that the NPS would make policy changes. Russell then encouraged CWRA members to submit complaints to Antietam Superintendent Virgil Leimer.

In response to the NPS Director’s decision, women were not assigned work the cannon crew or conduct black powder rifle demonstrations at Antietam starting in 1982. That year, Antietam had three seasonal interpreters and Lammers was the only woman. She recalled how demeaning it was to not be allowed to interpret during black powder demonstrations, but still be required to clean the firearms afterwards.

Fighting Back

In July 1982, Lammers rejected the NPS directive that women conduct black powder demonstrations wearing NPS uniforms and protective “leather gauntlets,” and filed a discrimination complaint under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. She did so in part because safety regulations required that black powder demonstrators wear long-sleeved, natural fiber, period-accurate outer garments, since synthetics (like those in the short-sleeved NPS summer uniform) are dangerous and can melt to the skin. The suggested “leather gauntlets” also made the finesse needed to operate the firearms all but impossible. Lammers even reached out directly to Russell to explain her position, but Russell rejected her argument, feeling that the matter had already been settled by Director Dickenson’s actions.3New NPS Guidelines

The day after Lammers’s deposition, Director Dickenson drafted new living history guidelines endorsing widespread use of third person living history. The guidelines, later put into effect as Director’s Order 6 (1986), state that the NPS is “interpreting the past, not recreating it,” and that visitors should be informed that these programs are meant to “evoke only a small segment or aspect of the past” to help better understand it.6

Dickenson’s guidelines also noted that the historical accuracy that the NPS hoped to evoke in its demonstrations was centered around the information NPS staff presented and “not with the authenticity of the individual’s race, ethnic background, or their sex.”7 The new guidelines were prepared in response to Lammers’s complaint as well as similar complaints involving female, Native American, and Asian American employees at other parks.

The Title VII complaint was resolved in July, with no party admitting fault. The resolution allowed female employees to conduct Civil War cannon demonstrations at Antietam while wearing soldier uniforms as required in their job descriptions. Additionally, female interpreters were required to “clearly identify to the visitors that a few women were disguised as soldiers in the Civil War, that four such women were at the Battle of Antietam,” and that there were primary sources available to support this assertion.8 Park interpreters also had to announce, prior to each firing, that the program was a “demonstration” and not living history. Recalling the events nearly forty years later, Lammers considered the result a “sweet victory.”9

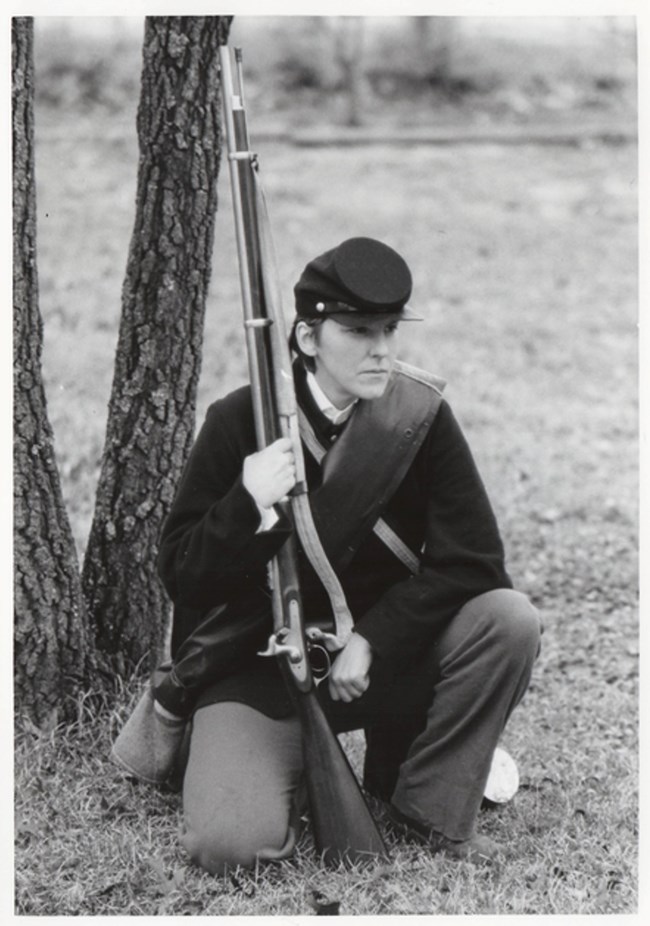

Photo courtesy of Lauren Cook Wike.

Case 2: Interpreting a Civil War Field Hospital

In August of 1987, experienced reenactor Lauren Cook Burgess arrived at Antietam to perform as a volunteer living historian with the 21st Georgia Volunteer Infantry. She was dressed as a fifer for aplanned “Aftermath of the Battle” event.10 The event aimed to interpret Civil War medicine by recreating scenes of treating wounded soldiers and staging a field hospital.11The agreement between the 21st Georgia and the park called for at least ten “members” of the unit to portray wounded soldiers with period-appropriate medical props and no weapons. It also called for “six female members” to portray local farm women and women seeking relatives on the battlefield.

A Contested Confrontation

In the first ranger’s account, he left the Visitor Center to confront Cook about her uniform (stating that the uniform was improperly cut and made from incorrect materials) and to tell her she was recognizable as a woman due to her “hair, figure, and traces of makeup around her eyes.” Cook disputed these statements, both at the time and thirty years later, maintaining that neither ranger realized that she was a woman until they witnessed her leaving a women’s restroom.Other details about the Cook-NPS interactions were also contested. Cook recalled an uncomfortable exchange in which the two rangers present that day told her to either change out of her uniform (and into a historic woman’s dress or modern clothes) or leave the park. The first ranger recalled that he told Cook that her character—an unwounded musician with a rifle—was not part of the day’s programming.

What is not contested is that after Cook approached the first ranger again to protest, the ranger brought Cook and her husband, as well as 21st Georgia leader Dave Pridgeon, to Antietam Superintendent Rich Rambur's office.

There is disagreement about what occurred in Rambur’s office. NPS staff stated that Cook refused to abide by NPS living history policies, while Pridgeon contended that NPS organizers never explained why Cook could not participate beyond her gender. The meeting did little to resolve the dispute, and Cook was effectively left with the same choices as before: change or leave.12 Cook and her husband left. She returned the next day to participate in the event as a woman civilian in period dress.

A week later, Cook wrote a letter to Antietam Chief Ranger Ed Mazzer (supervisor of the two park rangers involved), saying that she intended to file a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Oddly, no other communication occurred until three years later when on March 7, 1990, Superintendent Rambur wrote to Dave Pridgeon to specifically note the 21st Georgia’s poor performance. Rambur noted the park’s agreement was for "ten members to portray infantrymen and several of your females to do an impression of local women” however the 21st Georgia arrived with “children and one female who wanted to do a fifer impression.”13

Cook v. Babbit

Cook filed a federal discrimination lawsuit on February 14, 1991, against Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbit. Babbit’s office was targeted because the Department of the Interior was ultimately responsible for the actions of NPS employees and because Cook’s argument was based in Constitutional law.14 Cook’s argument was simple – there were over 400 documented examples of women who fought in the Civil War, including at least two who were present at Antietam, so why should she be barred from portraying one during living history events?NPS leaders attempted to apologize a few weeks before the lawsuit was officially filed “for the miscommunication,” according to Cook, but she rejected the apology. Cook and her attorney argued that the NPS should be forbidden from using gender as a factor in casting for living history interpretation, for NPS leaders to formally reprimand Antietam staff, and that the agency be required to refrain from retaliating against the 21st Georgia. The Department of the Interior’s immediate response was to deny any wrongdoing and state that all the NPS staff’s actions were in the interest of historical accuracy.15

Most of Cook’s argument lay in three pieces of evidence that were undisputed by the NPS: affidavits related to conversations between NPS staff and the 21st Georgia, written agreements between Antietam and the 21st Georgia, and Lammers’s 1982 discrimination complaint. Judge Lamberth determined that the Lammers complaint was not relevant to Cook’s case because it did not prove discriminatory patterns. However, the complaint did result in new NPS guidance, later incorporated into Director’s Order 6 (1986), including the following passages which were relevant to Cook’s case:

The selection of personnel for presentations must not abridge employee rights or opportunities for job experience in which they have a career interest and qualifications. We must be concerned with the accuracy of the information the interpreter presents and how effectively it is presented, not with the individual's race, ethnic background, or sex.

In general, [Living History] should be used only for very special situations. When planning, be sure that the decision to utilize first person does not result in unintentional discrimination in hiring, training, promotions, opportunities, etc.18

Lamberth ruled in Cook’s favor on March 17, 1993, finding Antietam’s policy of “categorically barring women from portraying male soldiers” constituted unconstitutional discrimination against women. However, Lamberth did not extend the ruling to the entire NPS; instead, he encouraged the NPS to issue new living history policy. Key to the decision were the written agreement between Antietam and the 21st Georgia and the March 1990 Rambur letter. Both documents acknowledged that the agreement between the agency and the reenacting group had not specified the gender of the participants would portray soldiers, so there was no reason why Cook should have been disallowed. The judge also noted that Cook was approached personally by NPS staff when standard protocol was to discuss with volunteer leaders, which further suggested she had been singled out for her gender.

NPS / Matt Borders

Conclusion

The experiences of Pat Lammers and Lauren Cook and their dedication to presenting accurate history, as well as their commitment to defending their civil rights, pushed the National Park Service to confront and correct its own role in inequitable treatment of those involved in living history. Because these two women stood up for their rights, National Park Service revised their policies. This paved the way for both employees and volunteers, to fully participate in historic weapons and living history programs at Antietam and other NPS sites without regard to the race, ethnic background, or gender.The NPS is always learning and working to share the stories from history for the education and enjoyment of its visitors, as well as sharing the stories of those who have influenced, and continue to influence, the parks and park service itself.

Footnotes

1 Per NPS Director’s Order #6 (2005) and NPS Management Policies (2006): It is important to note that battle re-enactments and demonstrations of battle tactics that involve exchanges of fire between opposing lines, the taking of casualties, hand-to-hand combat, or any other form of simulated warfare, are prohibited in all parks. Battle re-enactments create an atmosphere that is inconsistent with the memorial qualities of the battlefields and other military sites placed in the National Park Service’s trust. The safety risks to participants and visitors, and the inevitable damage to the physical resource [battlefield archeology and landscape] that occurs during such events are also unacceptably high when seen in the light of the NPS mandate to preserve and protect park resources and values.2 Snell, 513.

4 The demonstrations Lammers referred to were likely historical demonstrations. Policy at the time, defined living history as a type of demonstration.

6 Interpretation Guideline NPS-6, Release No. 3. December 1986.

8 Lammers-NPS Settlement Agreement, Lammers-NPS Lawsuit documents.

10 Note that some media outlets referred to her as Lauren Cook, Lauren Cook Burgess, and Lauren Burgess. Here she will be referred to as Lauren Cook as that was the name used on the final court filings. As of 2021, her name is Lauren Cook Wike.

12 Cook v. Babbitt, 819 F. Supp. 1 (D.D.C. 1993). Lynda Robinson, “Battle Re-enactor Finds Herself at War with U.S. Park Service,” Baltimore Sun, 30 Sep. 1991. Eugene L. Meyer, “A Civil War of the Sexes,” Washington Post, 9 Jun. 1992.

14 The specific legal argument was that Cook claimed her equal protection of the laws under the Fifth Amendment case were denied when ANTI staff did not allow her to portray a male soldier.

16 “Woman Sues Over Exclusion from Park's Civil War Events,” New York Times, 25 Feb. 1991.

18 Cook v. Babbitt, 819 F. Supp. 1 (D.D.C. 1993).

Sources

- Associated Press, “Woman Sues Over Exclusion from Park's Civil War Events,” New York Times, 25 Feb. 1991.

- Cook v. Babbitt, 819 F. Supp. 1 (D.D.C. 1993), U.S. Supreme Court, Justia Law, accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

- “Director’s Order #6: Interpretation and Education” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C. 2005.

- Eugene L. Meyer, “A Civil War of the Sexes,” Washington Post, 9 Jun. 1992.

- Eugene L. Meyer, “Judge Admits Women to the Antietam Armies,” Washington Post, 18 Mar. 1993.

- Howard, Josh. Unpublished research towards an Antietam Administrative History (1978 to 2016). Produced through an agreement with the Organization of American Historians for the National Park Service.

- Kaufman, Polly Welts. National Parks and the Woman’s Voice. University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

- Lynda Robinson, “Battle Re-enactor Finds Herself at War with U.S. Park Service,” Baltimore Sun, 30 Sep. 1991.

- Management Policies 2006. Cultural Landscape Guidance Documents. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C. 2006.

- Pat Lammers Interview, Antietam National Battlefield Oral Histories.

- Snell, Charles W., and Sharon A. Brown. “Antietam, National Battlefield and National Cemetery, Sharpsburg, Maryland: An Administrative History.” National Park Service, 1986.

- Susan Moore Interview. Antietam National Battlefield Oral Histories. 2021.