Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

Embattled Farmers and the Shot Heard Round the World: The Battles of Lexington and Concord (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

"By the rude bridge that arched the flood

Their flags to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.”1

Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the most noted residents of Concord, Massachusetts, penned these words for the town’s bicentennial in 1835. In April 1875, for the Centennial Celebration of the Battle of Concord, another Concord native, sculptor Daniel Chester French, created his first great public work. Emerson’s words were incised on the stone pedestal.

A century before, a group of express riders, including Paul Revere, rode across the Middlesex County countryside. They did not shout “The British are coming! The British are coming!” as myth would have us believe. Rather, the riders warned that the King’s troops were on the march, arousing the embattled farmers praised by Emerson. At that time the riders and farmer alike were still loyal subjects to England’s King George the III. Independence was the furthest thing from their minds. Instead, these minute men and members of local Massachusetts militia assembled to defend their rights, as they perceived them under English law.

British General Thomas Gage had ordered 700 soldiers to march in what he thought was a clandestine operation. His objective was to destroy the cache of colonial weapons located in the town of Concord. Within twenty-four hours, more than 70 of the King’s finest troops lay dead and many more wounded. Forty-nine provincials died, as well. One of history’s greatest unintended consequences proved to be the nascent seed that launched a revolution, forever changing the world.

Visitors can stroll across Concord’s Old North Bridge. They can pass the graves of two English soldiers killed in the exchange of gunfire across the Concord River, examine French’s sculpture, and walk along the shade lined “battle road.” Today, in this tranquil setting, how can one help but ponder how a nation could rise from the ashes of an event that was never supposed to happen?

1 Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Early Poems of Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York, Boston, Thomas Y. Crowell & Company: 1899.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Minute Man National Historical Park” (with photographs), and historical and modern accounts of the battle. It was written by James A. Percoco, Director of Education for the Friends of the National World War II Memorial and a former high school history teacher, and edited by Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in units on the Revolutionary War or in courses on conflict resolution.

Time period: Colonial/Revolutionary

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Embattled Farmers and the Shot Heard Round the World: The Battles of Lexington and Concord relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands the causes of the American Revolution.

-

Standard 1B- The student understands the principles articulated in the Declaration of Independence.

-

Standard 1C- The student understands the factors affecting the course of the war and contributing to the American victory.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Embattled Farmers and the Shot Heard Round the World: The Battles of Lexington and Concord relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

- Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns, cultural transmission of ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, & Governance.

- Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard F - The student explains conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

- Standard E - The student explains and analyzes various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

Objectives for students

1) To describe how the events in Massachusetts in early 1775 led to the outbreak of hostilities between England and her colonies.

2) To explain the significance of the Battles of Lexington and Concord and describe the unintended consequences of the battles.

3) To explain how myth, history, and memorialization are related and how they create or shape public memory.

4) To identify a person in the students’ own community who has made an important contribution and design a memorial to that individuals place and memory.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) Two maps showing the locations of Boston, Concord, Lexington, and the Minute Man National Historical Park;

2) Four readings about the causes of the battle and the fighting, the Minute Man statue, and the Longfellow poem;

3) Seven images including three photographs of the Minute Man Statue, the North Bridge, and the Battle Road; and four illustrations of the battle by Amos Doolittle and Don Troiani.

Visiting the site

Minute Man National Historical Park is administered by the National Park Service. The Minute Man Visitor Center is located at 250 North Great Road, Lincoln, Massachusetts. The site is open daily, except January 1, Thanksgiving, and December 25. For more information, write 174 Liberty St. Concord, MA 01742 or visit the park website.

Setting the Stage

|

In December 1773, in an era of increasing tensions between England and her American colonies, American patriots in Boston staged the Boston Tea Party. Massachusetts was at the forefront of colonial agitation and resistance and in response to the Tea Party, England’s Parliament, with the support of King George III, decided to punish Boston and Massachusetts by passing the Coercive Acts (known as the Intolerable Acts in the colonies). These acts shut down the port of Boston and suspended the colonial assembly. To show how serious the government was, England sent large numbers of British troops to be garrisoned in Boston to enforce the law as the Royal Navy ringed the port with their warships to keep Boston harbor closed. These actions cut off trade, crippled the economy, and put colonists out of work. British soldiers and colonists, now living in close proximity, frequently brawled in the streets and in the taverns. |

|

1 The Journals of each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State, Boston, 1838, pp. 33 - 34.

|

Questions for Map 1

1) Find the towns of Concord, Lexington, and Boston. Where are the routes someone could travel from Boston, through Lexington, and then to Concord? Trace them.

2) Find the people labeled “Militia,” “Provincials,” and “Minutemen.” Who do you think they are fighting? What evidence supports your answer?

3) What event in American history do you think this map illustrates? What clues can you find on the map to support your answer?

Locating the Site

Map 2: Minute Man National Historical Park.

Questions for Map 2

1) Locate the towns of Lexington and Concord. Locate the Minute Man National Historical Park. What manmade feature does the largest part of the National Park cover?

2) Use the scale located in the bottom-left corner of the map and a ruler to measure the distance between the two towns along the historic road. If English soldiers marched at a pace of 2 miles per hour, about how long do you think it would take for them to travel from Lexington to Concord? About how long would it take a horse to gallop between the towns at 30 miles per hour? Compare Map 2 with Map 1. Approximately how long do you think it would take to march from Roxbury Hill (south of Boston) to Concord?

3) Compare the two maps again and find the places in Map 2 where Map 1 shows people. Find the national park lands in Map 2. According to Map 1, what happened in the two areas where the national park is today? Why do you think these places were chosen to be the national park?

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: More Than One Side to Every Story

As with all histories, there is more than one side to every story. Thomas Gage’s letter and the coverage of the battles in the colonial press illustrate how different the intentions can be portrayed depending on what side a person is on.

First-hand accounts of the battle are a useful source for determining different perceptions of the same event from opposite sides. Here are examples from both the British and colonial perspectives about the battles.

General Thomas Gage, Military Governor of Massachusetts, to the commander of the expedition, after recieving an order for the British to march on Concord to take possession of the patriots’ weapons:

Boston, April 18, 1775

Lieut. Colonel Smith

10th Regiment Foot

Sir:

Having received intelligence, that a quantity of ammunition, provision, artillery, tents and small arms, have been collected at Concord, for the avowed purpose of raising and supporting a rebellion against his majesty, you will march with the corps of grenadiers and light infantry, put under your command, with the utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize arms, and all military stores whatever. But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants, or hurt private property.

Your most obedient humble servant

Thomas Gage1

Lt. John Barker, British Soldier, 4th Regiment, Diary Account on the beginning of the march to Lexington:

[April] 19th…about 5 miles on this side of a Town called Lexington which lay in our road, we heard there some hundreds of People collected together intending to oppose us and stop our going on: at 5 o’clock we arrived there and saw a number of People, I believe 2 and 300, formed on a Common in the middle of the Town; we still continued advancing, keeping prepared against an attack tho’ without intending to attack them, but on our coming near them they fired one or two shots, upon which our Men without any orders rushed in upon them, fired and put ‘em to flight; several of them were killed…2

Statement of James Barrett, Colonel of Concord Militia, on the Battle at North Bridge:

…I ordered said militia to march to said bridge and pass the same, but not to fire on the King’s troops unless they were first fired upon. We advanced near said Bridge, when the said troops fired upon our militia and killed two men dead on the spot, and wounded several others, which was the first firing of guns in the town of Concord. My detachment then returned fire, which killed and wounded several of the King’s soldiers.3

Questions for Reading 2

1) What do you think was the purpose of General Gage’s orders? What specific order does Gage issue regarding the treatment of local inhabitants?

2) Compare General Gage’s order with the account in Reading 1. How well do you think his orders were carried out?

3) How do the first-hand accounts differ? What does this mean for people trying to study this historical event and its place in the Revolutionary War? Do you think the first shot being fired on either side make a significant difference in larger conflict of the Revolutionary War? Why or why not?

2 “Diary of a British Soldier”, Atlantic Monthly, April 1877 Vol. 39.

3 The Journals of each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, p. 674, Boston MA. Dutton and Wentworth, 1838.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Fact or Fiction

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote the famous poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride” almost a century after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Published in 1861, Longfellow’s poem reveals the type of memory Americans wanted to have of the events of April 18, 1775. The following paragraphs from the poem help us understand how 19th century Americans remembered Paul Revere’s midnight ride:

Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, "If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,--

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm."

...So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm,---

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo for evermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.1

This historical poem about Paul Revere gives the reader a heroic impression of his ride to Concord and Lexington to warn people about the British troops. In reality, he rode for a short time before the British captured him.

While passing through Lexington at around midnight, Revere and William Dawes met Dr. Samuel Prescott of Concord, who was riding home after courting Lydia Mulliken. Prescott agreed to help them spread the alarm that “the [British] Regulars were out.” The three men ran into a patrol of ten British officers on horseback. These officers had been ordered to keep the news of the British march from reaching Concord. Revere was captured. Dawes escaped back toward Lexington. Prescott jumped his horse over a stone wall and escaped. Prescott, not Revere, carried the alarm to Concord and beyond.

The British questioned Revere and held him for a while before releasing him. They let him go, but the British officers confiscated his horse. Revere walked back to Lexington in time to hear gunfire at dawn on the town common.

Questions for Reading 3

1) What is the tone of this poem? What impression does it give the reader about Paul Revere?

2) What actually happened when Paul Revere was on his way to warn the towns about the British? When did he reach Lexington?

3. What does the difference between the poem and reality say about the study of the past when popular culture (Longfellow’s poem) and actual history collide?

1 Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Atlantic Monthly. January, 1861.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: The Minute Man Statue

For the nation’s 1876 centennial celebration the town of Concord wanted to commemorate its role in the nation’s birth. Ebenezer Hubbard, a Concord resident, had died recently and left in his will a thousand dollars to the town. He wanted the town to use his money to commission a memorial for the spot where the Americans fell on April 19, 1775. A prominent Concord resident, John S. Keyes, suggested that a local sculptor and family friend named Daniel Chester French create “a model for a large figure for a monument on the hill where the minute men assembled for the Concord fight.” The town set up a committee in 1872 and gave the committee a year to decide what form the monument should take. The committee’s report to the town suggested it “procure a statue of a Continental Minute Man, cut in granite, and erected on a proper foundation.” The committee also recommend that the design include the first stanza of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Concord Hymn on its base:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled;

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.1

The committee decided that 25-year-old French should make the statue after the committee approved of his model. He worked on his small scale model from April to June in 1873 and the committee approved of his design. The city formally awarded the commission to French in November. This was French’s first full scale statue and he drew inspiration from classical antiquity’s Apollo Belvidere, a sculpture to the Greek god Apollo. French admired the stance and incorporated it into his statue. The Minute Man figure’s right knee is flexed, with the right foot pushing off the ground, and the left leg is slightly flexed, with the left foot planted firmly on the ground. This position suggests forward motion.

French worked on the full-scale model in 1874. He sculpted and prepared the figure for delivery to the foundry, the place where bronze sculptures are cast. The final bronze figure was unveiled on April 19, 1875 at a ceremony attended by President Ulysses S. Grant. The statue depicts an “ideal figure,” which is a statue that represents an idea.

French’s ideal figure was a local farmer-citizen-patriot, responding to the call to action. In the figure’s right hand he holds his musket. His left hand rests on the handle of his plow. His gaze is intense and focused straight ahead of him. The minute man’s coat is draped across the plow. The plow relates directly to the idea of a farmer dropping his work at a minute’s notice heading off to defend himself and his community. Clearly, the accurate treatment of the plow, the coat, and the musket enhances the willingness of the militiaman to leave his work and join the impending fight, yet these details do not harm the pose. The sculptor used these details to make the figure’s identity clear. Local legend has it that French modeled the plow on that of Captain Isaac Davis, of the Acton Company. Davis died during the fight with the British at the bridge, therefore he was the first American officer to die in the War for Independence. For an inexperienced artist, The Minute Man is a work of exceptional power and spirit.

Questions for Reading 4

1) Why did residents of Concord want to erect a statue to commemorate the fight at the North Bridge?

2) What items does French use to convey the image and ideals of the minute men? What does each item mean?

3) How successful do you think Daniel Chester French was in conveying the idea of the minute man? Why?

4) Would you have chosen a different theme or symbolism? Why or why not?

Reading 4 was adapted from several primary sources including Journey Into Fame: The Story of Daniel Chester French (1948) by Margaret French Cresson, The History of American Sculpture (1903) by Lorado Taft, Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields (1991) by Edward T. Linenthal, and Michael Richman’s Daniel Chester French: An American Sculptor (1976) by The National Trust for Historic Preservation.

1 Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Early Poems of Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York, Boston, Thomas Y. Crowell & Company: 1899.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: The North Bridge Today.

Questions for Photo 1

1) Referring back to the readings, explain in your own words what happened here. What features do you recognize from the readings?

2) How is the landscape different from 1775? How is it similar? Do you think a minute man would recognize it? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

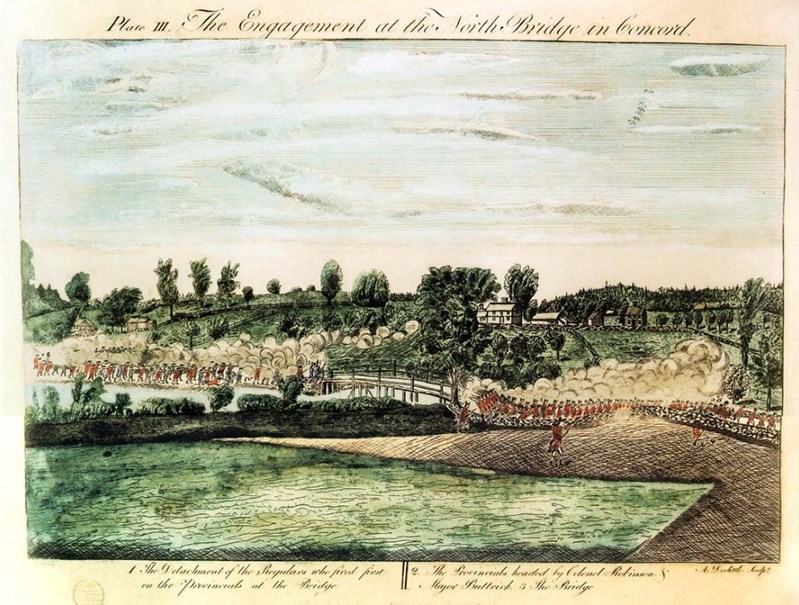

Print 1: Fight At the North Bridge,

by Amos Doolittle.

Caption, below engraving: 1. The Detachment of the Regulars who fired first on the Provincials at the Bridge || 2. The Provincials headed by Colonel Robinson & Major Buttrick. 3. The Bridge

Questions for Print 1

1) What group of people is to the left of the bridge? What group do you think is to the right of the bridge? What makes you think so?

2) Describe what is happening in this Doolittle drawing. What action do you see?

3) Compare the depiction of the battle and the soldiers in this drawing with what you read in the Readings and saw in Photo 1. What is similar? What is different?

Questions for Painting 1

1) Who do you think are the people in this image? Where do you think they are? What are they doing? (Refer back to the readings if necessary)

2) What emotions do you think the artist choose to have these men express? How do you know? Why do you think he chose them?

3) How does this scene compare with the same scene in Print 1? What is similar? What is different? Why do you think there are differences between these two perspectives?

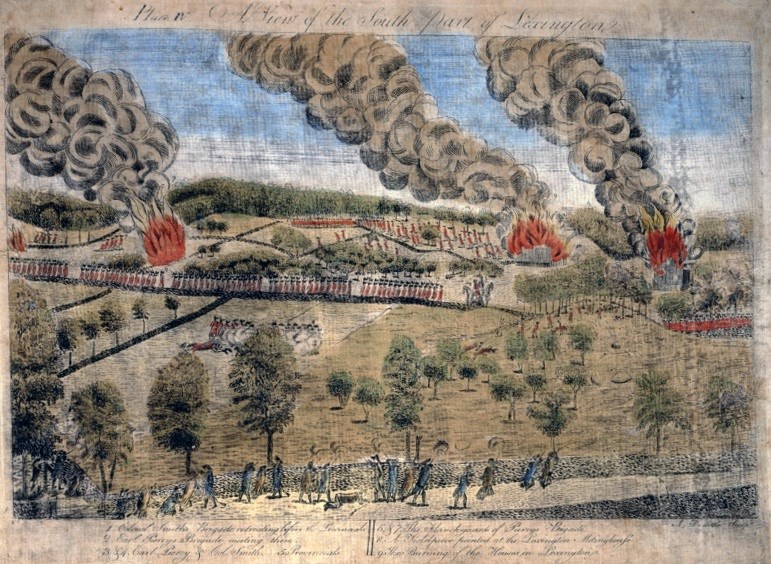

Print 2: The Battle Road, 1775,

by Amos Doolittle.

Caption, below engraving: 1. Colonel Smith's Brigade retreating before the Provincials 2. Earl Percy's Brigade meeting them 3. & 4. Earl Percy & Col. Smith 5. Provincials 6. & 7. The Flanck-guards of Percy's Brigade 8. A Fieldpiece pointed at the Lexington Meeting-house 9. The Burning of the Houses in Lexington

Questions for Photo 2 and Print 2:

1) List the manmade features in Photo 2. List the natural features in this photograph. Do you think road could have looked like this in 1775? Why do you think so?

2) Compare Print 2 with the information you found in the readings and in Photo 2. Do the contents of Print 2 confirm or conflict with that information?

Visual Evidence

Painting 2: Parker's Revenge, April 19th, 1775,

by Don Troiani.

Questions for Painting 2

1) How does this scene depicted here compare with the same scene in Photo 2 and Print 2?

2) What do you think accounts for the similarity? What do you think accounts for the differences?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Minute Man Statue.

(Detroit Publishing Company Collection of the Library of Congress)

Questions for Photo 3

1) What does the photo depict? What features can you see in the photo that are described in Reading 4?

2) What connections can you make between this sculpture and the evidence in the images? What connections can you make between this sculpture and what you read in Readings 1, 2, and 4?

3) Do you think the sculpture accurately shows what happened in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775? Why or why not?

Putting It All Together

In the lesson, students learned about the first battles of the Revolutionary War and the ways people remembered them through art. Through the following activities students will expand on these topics to explore revolution and commemoration through art.

Activity 1: Rebellion -- Then and Now

Ask students to use U.S. history textbooks to make a list of reasons the British colonists rebelled against the British government. Then, ask them to use newspapers, magazines, or news reports to make a list of countries that have recently undergone or are currently undergoing a revolution or change in government. Have the class choose one of these countries. Then divide the students into two groups, and have one group defend the government before the revolution and the other group present reasons why the rebels want change. Ask students from both groups if they find any parallels between America’s revolution and what is happening in the countries they studied. Then hold a general classroom discussion about the effectiveness of revolutions as a way to settle serious issues. Ask for other ways. What factors do people need to consider when deciding on the most appropriate or necessary course?

Activity 2: Recitation: “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere”

Have students read the entire Paul Revere poem. After completing this lesson plan, what do they think is accurate in the poem and what is not? Hold a class discussion about why Longfellow might have written the poem the way he did. What might be the values or use of any of the inaccuracies that Longfellow writes? How skeptical should we be of popular culture portrayals of history? Do all authors seek to shape history to their own advantage? Next, ask students to pick a current or recent event they think is important enough that it should be remembered by posterity. Ask them to think about how future generations should view this event and why, and then have them write a poem about it. Ask for volunteers to read their poems in class.

Activity 3: Local Commemoration

Ask students to work in groups to identify and research residents of their community who made positive contributions either locally or more globally. Have them consider more than those who serve in the military and have each group select a different person. The person that they research may be living or deceased. After they finish their research, ask each group to prepare a proposal to erect a suitable monument for this person and to present that proposal to the class. The proposal should include a testimony as to why the community should raise such a monument and a description of the form the monument should take. Have the class decide which of these people they would like to sponsor for such a monument. If that person is still living, ask the students to submit a design for a monument to the community member that they want to honor. With the permission of a living person, or if the person is deceased, have the class polish its proposal and submit it to the town council, city board, or other appropriate governing body.You might consider arranging for students to testify in person to community elected officials.

An alternate approach could be to have students design a community monument to an event, movement, or cause that affected their community or to a group of people important to their community. Students should research their chosen subject and prepare a proposal for the monument design.

Embattled Farmers and the Shot Heard Round the World: The Battles of Lexington and Concord --

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Embattled Farmers and the Shot Heard Round the World: The Battles of Lexington and Concord, students can more easily understand how the American War for Independence began. The conflict here put the English colonies on the road to separation from Great Britain and led to, in 1776, the signing of the Declaration of Independence the creation of the United States of America. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of materials.

The American Battlefield Protection Program

The National Park Service's American Battlefield Protection Program provides detailed battle summaries of the Revolutionary War on its web site.

Boston National Historical Park

Boston National Historical Park is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web page provides details on the park and visitation information. Included on the site is a Virtual Visitor Center that guides you through the Freedom Trail, Charlestown Navy Yard, and other sites that demonstrate Boston's role in our nation's history.

Library of Congress

Search the "American Memory" collection on the Library of Congress web page for further information about the revolutionary time period. The following links are of special interest: Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention: 1774-1789, Words and Deeds in American History, the George Washington Papers, Map Collections: 1544-1999, and An American Time Capsule.

Liberty! The American Revolution

Liberty! is the story of the American Revolution two and a half decades of debate, rebellion, war, and peace. It begins after the French and Indian War and ends with the creation of the U.S. Constitution. Liberty! is an online companion to the PBS documentary, Liberty! The American Revolution.

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration offers a wealth of documents related to the Revolutionary War and the creation of the United States of America in their online exhibit hall. Visit "American Originals" to view documents such as George Washington's account of expenses while Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. Also visit "The Charters of Freedom" to see the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

Further Reading

Students interested in learning more may want to read the following:

Paul Revere’s Ride by David Hackett Fischer (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), The Minutemen and Their World by Robert A. Gross (Toronto: McGraw Hill, 1976), The Minute Men, The First Fight: Myths and Realities of the American Revolution (Pergamon-Brassey’s: Washington: 1989), Lexington and Concord by Arthur B. Tourtellot (New York: W.W. Norton, 1959) and The Day of Concord and Lexington by Allen French (Boston, 1925).

Tags

- revolutionary war

- colonial history

- massachusetts

- massachusetts history

- minute man national historical park

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- american independence

- military wartime history

- colonial

- 250

- america 250 nps

- art and education

- military history

- colonial america

- twhplp

- america 250