Doorways often serve as cultural symbols of access and entry. On the other hand, doors may act as physical barriers by preventing or allowing limited access to social spaces, thus functioning as mechanisms of power.

Article

Doors to Interpretation: Kingsley Plantation

People Shaping the Landscape

Zephaniah Kingsley, born to a Quaker father in England and raised in Charleston, South Carolina, was actively engaged with the Atlantic slave trade in Spanish Florida. In 1806, Zephaniah traveled to Cuba and purchased three female slaves, one of whom was Anta Majigeen Ndiaye of Senegal.

Once in Spanish Florida, Anta - who had became known as Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley - became wife to Zephaniah and mother to his children. The Kingsleys, their children, and slaves moved to Fort George Island in 1814, where Zephaniah originally leased property from John H. McIntosh. McIntosh had fled to coastal Georgia after the Patriots’ Rebellion of 1812, when invading U.S. troops attempted to end Spanish rule in East Florida. The Kingsleys later purchased the land and began reconstruction of the buildings and structures that had been destroyed in the rebellion.

Zephaniah Kingsley was a man of contradiction. As he actively participated in the Atlantic slave trade and plantation-style labor throughout his life, he also advocated for emancipation of freed slaves. He encouraged enslaved persons to live in familial units, practice African customs, and to engage in their own labor outside of the expected day-to-day tasks of the plantation. This, he suggested, decreased the likelihood of slave rebellions, ultimately reinforcing his business practices.

Zephaniah maintained numerous relationships with formerly enslaved women. The emancipation of these women and their children was seemingly important to Zephaniah, especially during the 1840s when dramatic shifts in laws and policies concerning enslaved persons threatened his family. Despite his liberal use of emancipation, Zephaniah never claimed to be an abolitionist. His use of slave labor until his death in 1843 is evidence of the deep-seated connection between slavery, agricultural plantations, and wealth.

NPS Photo / D. Herring

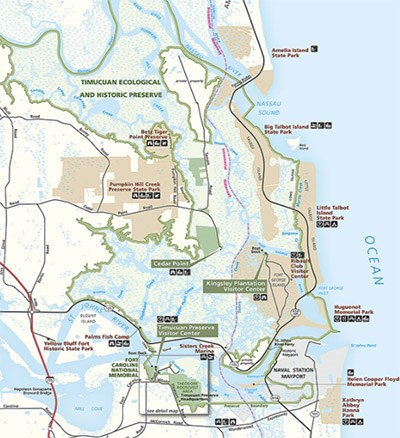

The landscape features at Kingsley Plantation illustrate the history of slave ownership, family relationships, and West African cultural heritage.

The semi-circular arrangement of slave cabins was part of the social-control system implemented at Kingsley Plantation, intended to facilitate familial connection and potentially believed to lessen the likelihood of uprisings by enslaved persons.

The kitchen, or Anna’s House, was constructed by the early 1820s. The ground level was used for food preparation, and the sleeping quarters on the second story provided a dwelling for Anna to raise the children. The development of the large-scale agricultural plantation was typical of its time in many ways. However, it is unusual for having an enslaved population that was now overseen by Anna, who was an anomaly in the region as a former slave who owned property and managed a large plantation. Her African heritage and cultural practices would have supported the creation of separate domestic spaces.

Implications for Interpretation

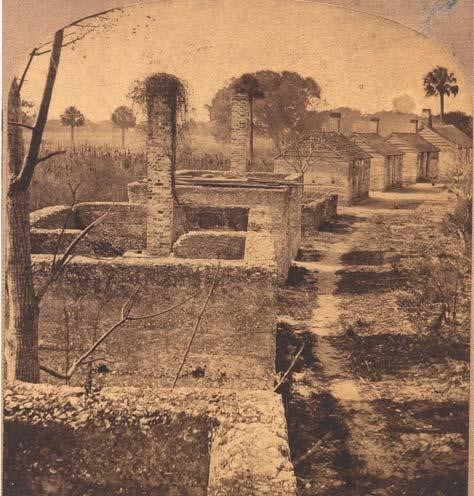

NPS Photo, in Historic Structures Report

Today, the Kingsley Plantation landscape consists of the main house, a kitchen, barn, slave cabin ruins, and over 51 acres. The main house was occupied by Zephaniah Kingsley, his wife Anna, and their children from 1814 to 1839. The detached kitchen served as the food preparation space and a sporadic dwelling for Anna and the children. The kitchen accommodated Anna’s expectations for separate living quarters. It also gave her greater access to the working portion of the plantation, and a place from which she could direct the daily operations.

South of the main house, a crescent formation of 32 cabins housed the enslaved population that was owned by the Kingsleys. It can be suggested that the spatial arrangement of these two areas of the plantation is indicative of the social hierarchy and power structure that existed at Kingsley Plantation, creating a specific relationship between the homes of the free and the enslaved. Further, the semi-circular orientation of the cabins potentially facilitated two key ideas:

- protection of the plantation from intrusion, and

- creation of community and space for enslaved persons.

Although it has not been confirmed, speculation surrounding Anna’s involvement with the orientation and construction of the slave cabins suggests the arrangement may be associated with her African descent. The semi-circular arrangement of dwellings may reflect the village complexes that she was familiar with in West Africa.

Although the majority of the dwellings were identical, four of them were larger by six feet on each side. These are believed to have been associated with foremen, or overseers. Each dwelling, including the larger ones, consisted of two-room layout with internal fireplaces. This type of internal spatial organization encouraged families to live together while also maintaining some independence.

Others have suggested that the arched orientation functioned simply as a mechanism for Zephaniah to maintain control, preserving visibility of the cabins while maintaining distance from those he enslaved. Whether the former or latter are true, it remains that the spatial organization of these cabins on the landscape, especially in the American South, is unique.

Accessing Complex Histories

Florida State Archives

As an atypically organized agricultural plantation, both in the family circumstances and spatial orientation, Kingsley Plantation’s history includes Euro-American wealth and power, enslaved African place-making by accessing space, and hints of creolization through African-American cultural practices. Entering the plantation area between the slave cabin ruins, visitors are exposed to the landscape where enslaved and freed Africans not only lived and worked, but also where they created spaces for their cultural practices within the two-room cabins.

The 2010 University of Florida archeological field school at Kingsley Plantation revealed previously unknown perspectives on enslaved African burials. Field school findings confirmed the existence of a cemetery associated with enslaved persons, located on the eastern side of the main road into Kingsley Plantation.

Florida State Archives

Knowledge gained about the manner in which rituals were conducted reinforces earlier archeological work, which found that African customs and culture were alive and well. For example, some individuals were buried with possessions such as ceramics, sea shells, and worked iron. With this evidence, used in conjunction with information about the complex lives of the plantation’s slave-owning inhabitants, NPS staff are able to open doors to diverse narratives and intertwined histories.

It is a challenge of immense magnitude to address diverse narratives in totality. Through continued research and partnerships, the NPS aims to discuss and present complexities between and beyond the enslaved persons and their masters to open a view to a more holistic history of a place. One of the most notable avenues for conveying history at Kingsley Plantation is an annual Kingsley Heritage Celebration (typically held the last two Saturdays of February).

References & Further Reading

Davidson, James M. Ph.D.

2011 “Interim Report of Investigations of the University of Florida 2010 Historical Archaeological Field School: Kinglsey Plantation, (8DU108).” Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve National Park, U.S. Department of Interior. https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/management/davidsonreport.htm. Accessed on January 9, 2018.

Jackson, Antoinette T. and Allan F. Burns

2004 “Kinglsey Plantation: Ethnohistorical Study of the Kingsley Plantation Community.” Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve National Park, U.S. Department of Interior.

Shafer, Daniel L.

2003 Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley: African Princess, Florida Slave, Plantation Slaveowner. University of Florida Press: Gainesville.

Shafer, Daniel L.

2013 Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. and the Atlantaic World: Slave Trader, Plantation Owner, Emancipator. University of Florida Press: Gainesville.

National Park Service

2007 Kingsley Plantation Cultural Landscape Inventory. Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, U.S. Department of the Interior. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2229892.

National Park Service

2015 “Kingsley Family and Society, Continued.” Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve National Park, U.S. Department of Interior. https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/historyculture/kp_family_society_p2.htm. Accessed on December 19, 2017.

National Park Service

2015 “Anna Kingsley: A Free Woman.” Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve National Park, U.S. Department of Interior. https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/historyculture/kp_anna_freewoman.htm. Accessed on December 19, 2017.

National Park Service

2016 “Anna Kingsley’s Story.” Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve National Park, U.S. Department of Interior. https://www.nps.gov/timu/learn/historyculture/kp_annakingsley.htm. Accessed on December 19, 2017.

Last updated: September 22, 2023