Last updated: December 30, 2019

Article

The Genesis of a Name

NPS

Pathway to Understanding

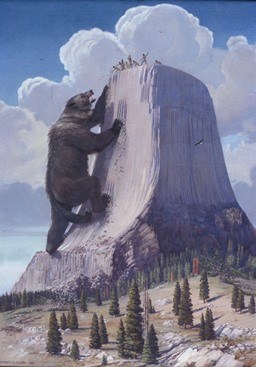

A common question asked at Devils Tower National Monument is “How did the Tower get its name?” Indeed, the name Devils Tower presents a contradictory dilemma, for once an awestruck visitor steps into the presence of the Tower nothing indicates a devil. The prevalent imagery is of a giant bear climbing the Tower, an indigenous story that explains how the Tower originated and how it got the grooves. These stories, unknown to most visitors, pertain to the original name of the Tower, Bear Lodge.To understand how the Tower’s name changed from Bear Lodge, one can look to the movement of European-American culture across the continent. This wave of cultural change began in earnest in the mid-1800s.

Clashing Cultures

When the Civil War ended in 1865, a divided nation united around western settlement. Westward migration, which began in the 1840s, increased. Indigenous people who lived in the region for thousands of years defended their territories from traditional enemies as well as these new colonists. Conflicts which had brewed and flared for decades intensified. The US government negotiated treaties with many nations of the Great Plains, but those treaties were broken time and again. The ideal of Manifest Destiny declared that there was not enough room for Native Americans and white settlers.

Courtesy of Custer State Park

Indigenous people were seen by many white Americans as a problem. The two cultures viewed the landscape with irreconcilable differences. Native Americans saw areas like the Great Plains and Black Hills as a resource to sustain their culture, while European Americans saw resources to be exploited for capital gain. The US government determined there were two solutions to this problem: assimilate Native Americans into white culture, or remove them entirely. Since Plains Indian cultural life depended so heavily upon bison (commonly called buffalo), many officials understood that destroying the latter would likewise destroy the former. Columbus Delano, President Grant’s Interior Secretary, wrote in 1872 that “the rapid disappearance of game from the former hunting-grounds must operate largely in favor of our efforts to confine the Indians to smaller areas, and compel them to abandon their nomadic customs.” Bison represented the infrastructure of Plains Indians, and any good military leader knew that destroying an enemy's infrastructure would cripple their efforts at resistance.

Non-government interests also drove the slaughter of North America's largest animal. Bison hides fetched a premium for many years, and railroads and telegraphs had no tolerance for animals that destroyed their equipment. Although there was no official government extermination program, only a few hundred bison remained by the 1880s. The loss of bison was a major reason Crazy Horse, the famous Oglala Lakota leader, finally surrendered in 1878; without food and clothing for his people, he knew he could not keep them safe. Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota, later said: "A cold wind blew across the prairie when the last buffalo fell—a death-wind for my people.”

Colonel Richard Irving Dodge, who would be the first to ascribe the name "Devils Tower" to the now-famous butte, proclaimed in 1867 that "every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” He later described the condition of the Great Plains: “Where there were myriads of buffalo the year before, there were now myriads of carcasses. The air was foul with a sickening stench, and the vast plain which only a short twelve months before teemed with animal life, was a dead, solitary desert.” It is within this changing ecological and cultural landscape that the name for the Tower changed from Bear Lodge to Devils Tower.

Library of Congress

Bear Lodge

American Indian tribes who lived in this region for approximately ten thousand years had their own names for the Tower. The descendants of these tribes are the modern Plains Indian nations with which the US government established relations. At different times in their histories, groups such as the Crow, Kiowa, Shoshone, Araphao, Cheyenne, and Lakota controlled the Black Hills or surrounding areas. Each of these groups have names for the Tower, and many of those names have similar English translations. The most common and widely used during the time of United States exploration of the Black Hills (1855-75) was Bear Lodge.The first government effort to accurately map the areas west of the Missouri River concluded in 1857. Produced by then-Lt. G. K. Warren, this map labels the Tower as "Mato Teepee or Bear's Lodge" - Mato Teepee being a common Lakota name. Warren's report cites encountering a group of Lakotas in the western Black Hills, and his map labels many Lakota tribes as controlling the region at this time. It is also notable that Warren's map labels other geographic features near the Tower with the same names in use today, such as the Missouri Buttes and the Belle Fourche River. Subsequent expeditions and maps, including Lt. Col. George Custer's from 1874, use the name Bear Lodge.

Today, numerous oral histories about the Tower's creation are recorded. Although each tribe has their own story, a common element to all narratives is a bear (or group of bears) scratching the large grooves which are seen on the formation. A lodge is synomynous with tipi and home, and many indigenous names translate to Bear Lodge/Home/Tipi.

NPS archives

Devils Tower

The first use of "Devils Tower" was by then-Lt. Col. Richard Dodge. In 1875, he commanded the military escort for a scientific expedition into the Black Hills. Keeping a journal during this expedition, Dodge wrote that "the Indians call this place 'bad god's tower,' a name adopted with proper modification..." And so the label "Devil's Tower" was created. No records indicate that Native Americans associated this place with bad gods or evil spirits. It is suspected that a bad translation led the men to confuse the words for bear and bad god. Others feel Dodge deliberately changed the name of an important indigenous site. Both ideas seem valid. The only records of Dodge's translator state his name as Romeo, a part-Cheyenne, part-Mexican. Romeo's knowledge of Plains Indian culture is unknown, as is his involvement in the translation; yet improper translation was common in US government relations with American Indians. Dodge's feelings about American Indians, decidedly elitist and often negative, are also well documented. Some argue his opinions influenced his thoughts on indigenous place names. In his book, Our Wild Indians, he concludes a generic description of American Indians: "In short, he has the ordinary good and bad qualities of the mere animal, modified to some extent by reason."Maps, members of Dodge's expedition, geologists, and government offices continued to use the name Bear Lodge. Dodge himself referred to the Tower as Bear Lodge, switching to "Devil's Tower" part-way through his journals. Dodge went on to publish a book about his expedition. The name Devils Tower became popularized and adopted by many white colonists. As the mining and timbers industries, and later the ranching industry, brought white Americans to the region, the site became Devils Tower. Indigenous groups had been pushed out, and the old name faded into obscurity. It lived on in the minds of American Indians who still knew their traditional stories

Changing a Name

The "Devils Tower" name likely became official in 1906 with the designation of the national monument. Regionally it had become known as "the Devil's Tower," and some wonder what happened to the possessive form. Earlier park materials cited a grammatical error, but it was more likely an intentional change. The US Board on Geographic Names (BGN) is responsible for naming places, and since their inception in 1890 they have a policy against using possessive place names. So the possessive "Devil's" was modified to the plural "Devils."It is reasonable to assume that American Indians have long disapproved of the name "Devils Tower." The names we give to places are more than map labels. A name represents the meaning which a place holds to a person or group. It helps us remember what a place is, who lives there, and why it is important. It identifies the significance of an area's history. The name Bear Lodge is a reminder of the site's significance to indigenous culture. Hence, many traditionally associated tribes prefer that name be restored.

In 2014, petitions to change the site name were submitted to several offices: the US BGN, the Department of the Interior, and the president. These petitions all asked the name "Devils Tower" to be changed to "Bear Lodge." Officially, the BGN is the agency with the authority to change a place name. Since the site is managed by the Department of the Interior, the Secretary of the Interior or their supervisor (the president) can use executive authority to change the name.

However, BGN policy also states that any name change proposal with active legislation will not be considered until that legislation is resolved. Since the 2014 petition, Wyoming's representative and congresspeople have submitted bills to retain the name Devils Tower. The bills are resubmitted every two years at the start of the new congressional session. Although not officially acted upon, their existence precludes the BGN from considering the Bear Lodge name change proposals.