The results from repeat surveys, and the knowledge of how different species are detected differently over a season, a day, and by different observers, alert park managers to any changes in the abundance, distribution, or seasonality of the many passerine birds that nest in Denali.

They come with subdued calls, rich and pleasing... Adolph Murie (referring to a Canada jay)

NPS Photo

It is hard to imagine how a tiny bird like the Ruby-crowned Kinglet—which weighs only as much as two or three pennies yet migrates thousands of miles to nest in Denali—can sing so loudly. But, being able to hear (or see) the Kinglet and other songbirds on their nesting grounds is the heart of the songbird surveys that biologists conduct in Denali National Park and Preserve. The goal of these surveys and the songbird monitoring program is to estimate accurately changes in songbird species abundance and distribution.

Songbirds belong to the Order Passeriformes or passerines. Passerine species in Denali include long-distance migrants such as flycatchers and warblers, and resident birds, such as Boreal Chickadee and Canada Jay. Passerines are found in all habitats in Denali ranging from wetlands to high alpine meadows.

The Importance of Detecting Birds Reliably

To assess whether bird species are increasing or decreasing in abundance over the years, it is critical that estimates of bird populations be based on accurate interpretations of the bird survey results. Songbirds are more often heard than seen during surveys. But the estimate of population size for Ruby-crowned Kinglets in the sampling area is not just the total number of Kinglet songs heard during the surveys. Population estimates depend on the survey technique used and must take into account the factors that influence bird detectability (ability to see the bird or hear a song). Since 2002, the protocol for monitoring passerine birds has undergone extensive revisions to incorporate new survey and analysis methods.

NPS Photo / Nathan Kostegian

To plan surveys that can be used reliably to compute population estimates for comparisons from year to year, researchers and statisticians with the passerine monitoring program for Denali and the other two parks in the Central Alaska Network (CAKN) asked three questions: Does it matter when during the nesting season surveys are conducted? Do bird species have different singing habits, so that the time of day would influence the survey results? Are the results consistent from one observer to another?

To answer these questions, i.e., to determine whether the probability of detecting each species changes across the nesting season, during the sampling day, and with different observers, beginning in 2009, researchers and field assistants have conducted repeat-surveys during the nesting season for songbirds in Denali. Statisticians also reviewed previously collected data from 1995 to 2009.

Conducting Repeat Bird Surveys

For repeat bird surveys in Denali, observers conduct bird surveys at 150 points along the park road spaced 0.5 mile (800 m) apart and at more than 600 points located up to 7 miles (12 km) away from the park road spaced about 0.3 miles (500 m) apart.

At each sampling point, an observer records all the birds detected during the timed survey (three minutes for roadside sites or ten minutes for off-road sites). The observer also records environmental data including weather conditions and background noise. The surveys start in late April when resident species are nesting and migratory species are setting up nesting territories and end in mid-July when males sing less. Surveys start within ½ hour of sunrise and continue for about six hours. The field crew returns to sampling points several times (3-12 for roadside, 2-3 for off-road) during the season.

Findings from Repeat Surveys

Seasonal variation

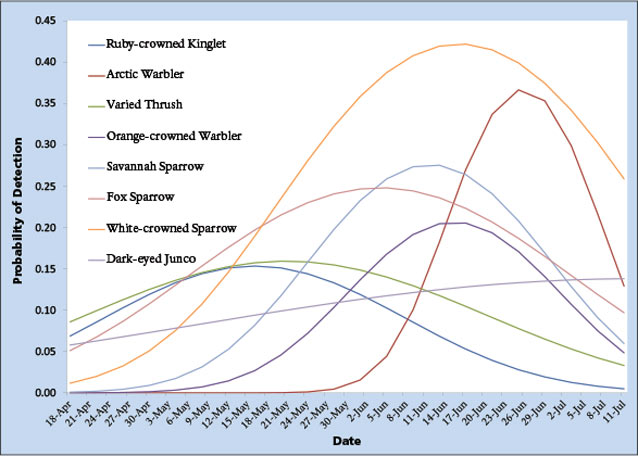

The probability of detection for each species varied across the nesting season (see patterns for eight species in upper graph at right). While many patterns took the shape of a bell curve, the peak probability of detecting birds occurred at a different time for each species. For example, the ability to detect an early-arriving migrant such as Ruby-crowned Kinglet (blue line) or Varied Thrush (green line) peaks and declines by the time later migrants such as Arctic Warbler arrive. In contrast to other species, the detection probability for the Dark-eyed Junco increases across the entire survey season. These results indicate that no range of dates is optimal for detecting all species. Thus, repeated surveys are needed to take into account the seasonal variation in the probability of detection of different species, to determine population sizes accurately.

Daily variation

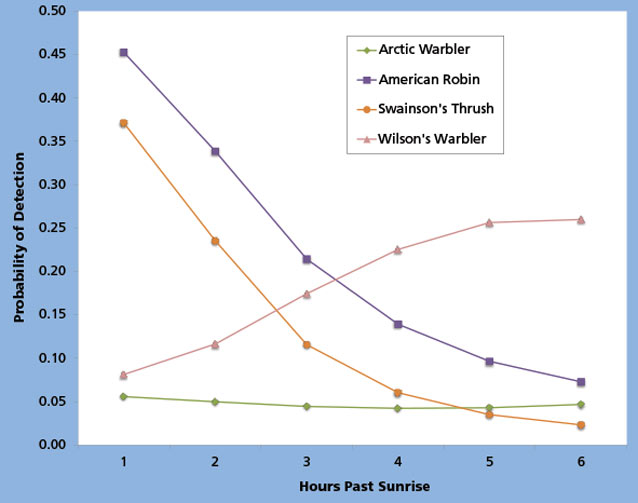

In the repeat-survey study, patterns in singing rates varied by species throughout the presumed “peak” singing period—½ hour before sunrise to 6 hours after sunrise (see lower graph at right). For example, for American Robin and Swainson’s Thrush, the detection probabilities are highest at sunrise and decline to near zero; for Wilson’s Warbler, the probability is nearly zero at sunrise and highest 4-5 hours after sunrise; and for Arctic Warblers, the probability remains nearly constant. Time of day influences the probability of detection of songbirds and needs to be built into calculations of abundance.

Variation by observer

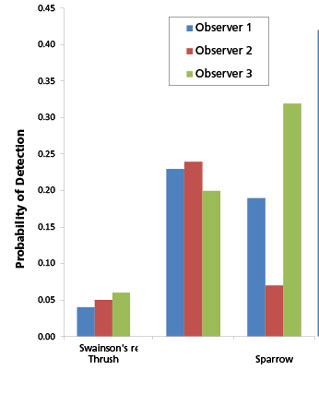

Although all Denali observers are trained intensively and are proficient at identifying birds in the study area, there are very large differences in detections of songbirds among even highly-trained observers (see graph at left). This “observer effect” must be incorporated into calculations of abundance and estimates of trends.

Interpreting Survey Results

After accounting for these three sources of variation in detection, researchers can estimate trends with confidence. Over the 15-year study period, they estimated that on average along the park road, Fox Sparrow abundance increased at a rate of 6.4 percent per year while Wilson’s Warbler abundance decreased at a rate of 4.3 percent per year. Thus, in 2009, Fox Sparrow abundance was 250 percent (2.5 times) greater while Wilson’s Warbler abundance was 50 percent (half) what it had been in 1995. No change was detected in abundance for the remaining species of songbirds.

When the Ruby-crowned Kinglet sings at dawn, observers may detect the loud and clear notes of the intrepid songbird. But hearing a song is just part of the bird monitoring story. It is only with the results from repeat surveys, and the knowledge of how different species are detected differently over a season, a day, and by different observers, that park managers will be alerted to any changes in the abundance, distribution, or seasonality of the Kinglet or other passerine birds that nest in Denali.

Part of a series of articles titled Denali Fact Sheets: Biology.

Previous: Surveying Dall Sheep in Denali

Last updated: April 8, 2019