NPS photo

A thick blanket of haze obscured the park’s landscapes, except the very closest ridges. An acrid smell hung in the air and accosted the nose. The Friday Ridge hike off ered to lodge guests in Kantishna was abandonned for less strenuous activities. Many questions were voiced by both visitors and park employees about where the smoke was coming from. By the end of the summer, people were defi nitely fed up with the smoke, and didn’t care if it was natural or not. Visitors found an encounter with smoke can be downright frustrating, if smoke prevented views of “the mountain” they hoped to see. Local residents were more aware of the risk of wildfire and were concerned about their homes. The fire situation was in the news every day. A fi re staff person working in Alaska reported “There was so much smoke, it was like walking into a wall when going from being indoors to outside. When I went outside, I immediately had the urge to turn around and go back in. It was that bad.”

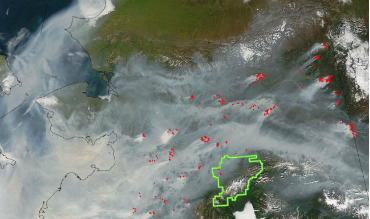

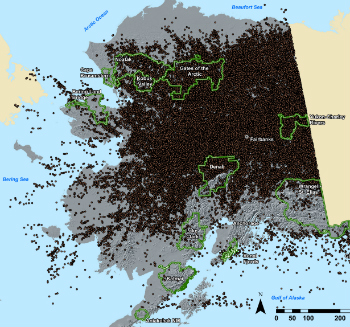

That was the situation in 2004, when smoke arrived and lingered in Denali National Park and Preserve for many weeks even though there were no wildland fires burning within the park. That summer, hundreds of wildland fires in Alaska burned a record 6.7 million acres and smoke was pervasive across Alaska.

In contrast, the summer of 2008 was a wet summer, few wildland fires burned, and smoke was not an issue. Who knows what the next season will be like and if smoke will be part of the scene? Smoke is, however, a part of most Alaskan summers.

NPS photo

Wildland fire ecology

Wildland fires are a natural part of Alaskan ecosystems, especially in forests of spruce—a species more prone to burning than many others. In Denali, large tracts of spruce occur in the northwestern portion of the park. A lightning strike may ignite a fire if it strikes dry fuels, i.e., live or dead vegetation. Given the unbroken sweep of spruce in the landscape, one fire can burn thousands of acres. For example, the 2002 Moose Lake fi re grew to 118,000 acres over the course of July and August. Large fires such as this create huge plumes of smoke.

The fire management staff maps and monitors where wildland fires are burning and notes proximity to remote cabins or communities—ready to take protective action if needed. However, wildland fires (and therefore smoke) are not often extinguished if they do not threaten life or property.

<p?Fires may burn patchily creating mosaics of burned and unburned areas. Black spruce cones opened by the extreme heat of fire shed seeds to warmed soils (post-fi re blackened surfaces absorb more sun). Vegetation grows back. Wildlife, including moose, which prefer willows and other plant growth, also benefit from renewing fires. Researchers are learning from fire evidence how often, on average, fire returns to the same location.

In brief, fire visits Denali frequently and is a constant force of regeneration for boreal forest vegetation. And smoke is a by-product of these wildland fires.

Smoke and how it travels

Smoke is a mixture of particles and gases given off through combustion. Smoke takes on different characteristics (e.g., color, density, smell) depending on what kind of vegetation is burning and how fast.

Winds transport smoke vast distances. Smoke is transported from its source by surface, low-level, and upper-level winds. Whether smoke is encountered in Denali depends on where wildfires are burning and the direction of the prevailing winds. The smoke may linger if captured in valleys or by a mass of air. A change in wind direction may remove or reduce smoke even though the wildfire remains active.

Smoke encountered at Denali may have originated from fires burning in the park, in surrounding areas, or in more distant areas (e.g., northern Alaska, Russia, or Canada).

Fires, and therefore smoke, may occur in Alaska from late April to late October. However, lightning strikes that trigger fi res are more common in mid-June through July. As the summer progresses, rains that typically begin in mid-August increase the moisture content of potential fuels such as mosses, grasses, and branches, thus decreasing the odds of fire. As daylength decreases, there is less sunlight to dry the vegetation sufficiently for it to ignite.

Smoke and a visit to Denali

If smoke is encountered as part of the Denali experience, keep alert for the need to modify activities because of health risks from breathing smoke. Because people with existing respiratory and heart ailments, children, and the elderly are particularly sensitive to smoke, activities should be planned with their smoke tolerances in mind. Physical exertion should be reduced by people and pets if smoke levels warrant. If visibility has been reduced to less than 2.5 miles, the health hazard of smoke is unhealthy and prolonged exertion should be avoided.

During a visit to Denali, if there is smoke, be aware of changing winds that may worsen or ameliorate the conditions. Every wildland fi re season is different. Consider the values of wildland fi re while tolerating the smoke. Smoke is a signal that wildland fire processes are renewing vegetation and habitat for wildlife as they have for millennia.

NPS photo

Managing smoke

Because of its inherent linkages to wildland fires, smoke cannot truly be managed. Putting out fires to reduce smoke is not always possible or desired, although fire managers try their best to manage (reduce) smoke impacts to human communities. Smoke management is even more complicated when there is more than one large fire in the area, as is often the case in Alaska. However, the safety of firefighters and the public is always the No. 1 priority of all NPS wildland fire management activities.

Last updated: October 26, 2021