NPS photo

The early stampede (c. 1905) of fortune seekers to the Kantishna Mining District subsided quickly, yet mining continued intermittently there through 1985. Early miners sought color in Kantishna with gold pans and patience, later others developed more mechanized and larger volume mining, bulldozing streams to move large amounts of gold-laden gravels, or excavating hard rock mines. While some miners cleaned out their camps and put lands back closer to a pre-mining state before they moved on, some abandoned their dreams—along with their heavy equipment and the debris of living in mining camps. Part of the legacy of Kantishna mining was holes in the hillsides, non-functional floodplains, and streams downcutting and eroding banks and tailing piles.

Only massive restoration efforts could begin to fix the visible and invisible scars of mining on the stream ecosystems in Denali National Park and Preserve. The goal of restoration activities in Kantishna is to restore damaged stream reaches to some semblance of healthy stream function, including improved water quality, riparian habitat (vegetation), and aquatic life.

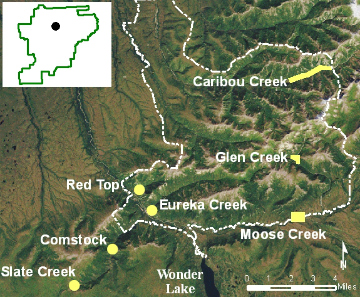

Restoration activities in Kantishna

Restoration activities typically include removing hazardous materials, contaminated soils, and abandoned equipment; reconstructing fl oodplain and stream channel structure; stabilizing stream banks from erosion; and revegetating the site. To evaluate restoration success, restoration also includes long-term monitoring of measures of stream function. To address this large-scale restoration need in Kantishna, the park received NPS funds for work in 2008-2011—prior to 2008, funding for restoration was limited and intermittent. Major eff orts are focused on Glen Creek (2009), Caribou Creek (2010), and Slate Creek (2010 or 2011), while smaller projects may occur at Eureka Creek, Moose Creek, and Crooked Creek. In addition, funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) were appropriated to safely close an adit (opening) at the Comstock Mine.

Legacy of mining claims in Denali

The mining claims staked in the Kantishna Hills, were outside Mount McKinley National Park. When the park tripled in size in 1980, Kantishna’s mining claims were inside the new park boundary. Because of legislation and a resulting court injunction, mining ceased in 1985 while the NPS prepared an Environmental Impact Statement on the cumulative impacts of mining in Denali. Based on the EIS alternative selected in 1990, NPS began to acquire the unpatented claims (surface land held federally, subsurface minerals held privately) through federal takings (reimbursing claim holders for the mineral value of their claims). Today only a handful of unpatented claims remain, while some patented mining claims (the surface and subsurface minerals held privately) are now private inholdings in the park.

As mined lands were acquired by the NPS, they were evaluated for possible restoration activities. Between 1990 and 2006, restoration occurred on sections of Glen Creek, Caribou Creek, Slate Creek, Eureka Creek, and Red Top Mine.

Placer versus hard rock claims

When active, Kantishna’s large-scale placer operations, such as Glen Creek or Caribou Creek, used bulldozers to move streambed materials through large-scale hydraulic wash plants to separate gold flakes and nuggets from other streambed materials. For these claims, restoration involves moving gravel to reconstruct stream flow, smoothing tailing piles, and replanting vegetation. Slate Creek and Comstock Mine are examples of hard rock or lode mining claims (excavation of rock or ore). Restoration is needed to fill pits or adits, prevent leaching of heavy metals, and recontour tailing piles.

Effectiveness of stream restoration

Denali staff is working with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Alaska Department of Conservation, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to track the water quality of the restored streams over time, to determine if restoration work has been eff ective at improving water quality. Development of native vegetation is also being monitored in cooperation with the USGS. A true measure of mining restoration success will be when Caribou and Slate Creek—now listed as impaired waterways under the Clean Water Act—can be taken off the list because they meet water quality standards.

NPS photo

After restoration planning in 2008, sites with restoration work scheduled for 2009-2001 included the following.

Glen Creek

Glen Creek was mined intermittently from its original gold placer claim staking in the early 1900s through 1985. The property is the site of abandoned mining debris, substantial soil contamination, and extensive mining-related impacts. A contractor worked from June to September 2009 to (1) remove buildings, mining equipment, and other debris, (2) characterize and excavate contaminated soils, (3) level tailings piles (see lower photo) and rebuild portions of the Glen Creek fl oodplain, and (4) revegetate disturbed areas.

NPS photo

Caribou Creek

Caribou Creek has the most extensive placer mining-related damage of any drainage in Denali (361 acres comprising 13.1 miles of aquatic and riparian habitat). Portions were dredged in the 1930s, and then aggressively reworked with heavy equipment in the 1970s and 1980s. Stream banks are devoid of vegetation and rows of tailing piles are evident (see aerial photo at right). Plans for 2010 include widening and smoothing the upper portion of the disturbed floodplain (last mined in the mid-1980s), creating a relief channel for flood events, and reinforcing some previously restored curves in the main channel.

NPS photo

Slate Creek

Slate Creek, a tributary of Eldorado Creek, has several adjacent abandoned lode claims including a semi-open pit style mine that was intermittently active from 1910 to 1983. This site consists of exposed mine walls that are leaching acidic minerals (see photo); 245 linear meters (~800 linear feet) of tailings piles; and an acidic stream section. Despite limestone buff er methods used beginning in 1998, acid mine drainage continues, and portions of the site remain barren. One recent in-stream pH measurement was extremely acidic (pH of 2.8). Plans for restoration in 2010 and/or 2011 include capping mineralized outcrops, backfilling the open pit, grading the tailings piles, and relocating and re-enforcing the stream channel.

NPS photo

Comstock Mine

Comstock Mine, adjacent to Eldorado Creek, is a turn-of-the-century hard rock property. To access the lode minerals, the four mining claims have underground workings at three levels. All the adits (horizontal entryways) are collapsed, preventing unsafe access, except one on Comstock claim #2 (see photo). This adit was re-opened in 2006 to determine the value of the mineral deposits and covered with plywood. More recently, loose gravel has sloughed over the boards. To close the adit more permanently, NPS staff will install a sturdy wood framework—filled with a foam core—and cover this new surface with local gravel and soil. The project, funded by the ARRA, is scheduled for 2010.

Last updated: July 28, 2016