NPS photo

In the Kantishna Mining District, beyond the end of the park road in Denali National Park and Preserve, placer mining of yesteryear severely disturbed many streams and watersheds—removing vegetation and topsoil, excavating gravel down to bedrock in the stream channels and floodplains, and leaving tailing piles that lack fine sediments and nutrients.

Stream restoration at Glen Creek

In 1991, the park began an experimental stream restoration project on Glen Creek, focusing on two stream reaches (sections) where the streambed was unstable and incised without functioning floodplains, i.e., the stream was moving around and eroding ditches through the placer mine tailings.

The objectives were to develop and test hydraulic designs for a channel and floodplain shape that would promote recovery to a more natural condition, test methods to stabilize the new floodplains with riparian vegetation to restore lost habitat, and provide information for future projects in similar degraded watersheds.

The principal investigators for the original project and the monitoring that followed were scientists at Denali—Dr. Roseann Densmore (ecologist, now retired from the U. S. Geological Survey) and Ken Karle (hydraulic engineer, now with Hydraulic Mapping and Modeling).

NPS photo

Bulldozers, front-loaders, and dump trucks were used to reconstruct floodplains and to move a stream section to the center of the valley from a ditch along the valley wall. Because the natural revegetation was expected to be slow, several bioengineering techniques were tested to help stabilize the new floodplains, including: (1) bundles of willow and alder branches partially buried at right angles to the stream to slow flood waters and encourage sediment deposition (brush bars), (2) buried willow branches with the ends sticking out of the stream bank (stream bank brush layering), and (3) willow cuttings planted along the stream. Willow plantings were tested with and without slow-release fertilizer. Feltleaf willow (Salix alaxensis) was used because of its importance in natural floodplain plant communities in the area.

Long-term monitoring after restoration

Long-term monitoring of stream restoration projects is essential to modify the project if needed (adaptive management) and to transfer the knowledge to the design of other projects. Densmore and Karle have monitored the Glen Creek project since construction. They have resurveyed established transects across the floodplain and stream, conducted analyses of water quality and soils, measured growth of planted vegetation and natural revegetation, and compared ground, aerial, and satellite photos.

NPS photo

Results of long-term monitoring at Glen Creek

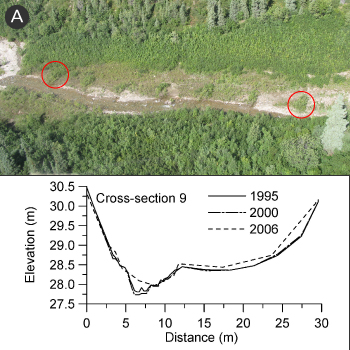

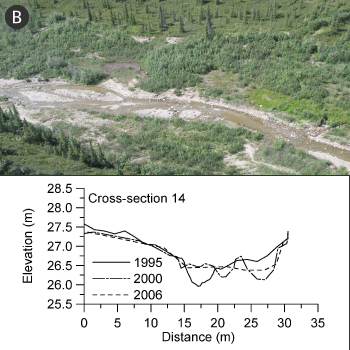

Floods are a critical test of the effectiveness of stream restoration projects. With transects in place, Densmore and Karle were able to measure the effects of a major flood after it occurred in 2000 and to measure the post-flood changes in 2006.

The flood caused immediate and significant changes in many areas of the stream project, while other areas withstood the flood. Figure A shows a stream reach that remained stable during and after the flood. The vigorous growth of fertilized willows in the brush bars and brush layering helped reduce erosion. In contrast, in the lower reach, one-third of the reconstructed floodplain was completely eroded when the floodwaters cut through naturally revegetated areas behind the brush bars. The crosssection in Figure B shows how the stream continued to become wider and shallower after flooding.

Two design flaws were revealed as a result of this long-term monitoring: (1) an underestimate of sediment volume moving downstream from the upper part of Glen Creek, both during floods and on an annual basis, and (2) an overestimate of the rate of natural regrowth in the low-nutrient gravels—regrowth was too slow to stabilize stream banks within the five to ten years the design relied on. As a result of these lessons, Denali has completed another project at Glen Creek to reduce excess sediment erosion from large piles of mine tailings near the Glen Creek headwaters.

NPS photo

A monitoring program for Caribou Creek

A similar restoration project was conducted in 2001-2002 at Caribou Creek. Baseline data on stream location and shape were collected, but there was not a program for long-term monitoring until Densmore initiated one in 2007—resurveying the location of the stream and stream cross-sections, and evaluating the natural revegetation of the reconstructed floodplains.

In 2007, Densmore was able to survey seven cross-sections and the channel location, and two vegetation transects. Other monitoring was impossible due to difficult access logistics (Caribou Creek is more remote than Glen Creek). So, Densmore also used aerial and satellite photos to confirm the widespread instability in stream channel morphology and the slow plant regrowth. In many areas, the stream channel has widened and become shallower, with considerable bank erosion, deposition of new gravel bars, and sparse revegetation. However, some streambanks were relatively stable, with willows, dwarf fireweed, and a crust of bacteria and lichens.

More restoration, more monitoring

Caribou Creek is slated for additional restoration to address deficiencies in the reconstruction already completed, and to reduce erosion and sediment load in a reach further upstream. Monitoring at Caribou, Glen Creek, and other restored streams will continue to provide valuable feedback to help park managers adapt and improve restoration protocols. Ultimately, the monitoring efforts are aimed at finding out the effects of the project on the ecological conditions of the stream and its riparian zone.

Last updated: July 28, 2016