NPS photo

Denali seems an unlikely place to look for toxic contaminants. The park, however, receives very small amounts of contaminants from global sources each year. Some of these contaminants persist in the environment, and can accumulate in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems over time.

In an effort to better understand the potential risks of toxic airborne contaminants in park ecosystems, Denali participated in a comprehensive study of contaminants in western parks from 2002-2007.

NPS Photo

Collaborative science

The Western Airborne Contaminants Assessment Project (WACAP) was a collaborative effort headed by the National Park Service and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in cooperation with scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Forest Service, Oregon State University, and the University of Washington.

The project focused on lakes and their watersheds, with two lakes sampled in each park. In Denali, the lakes were Wonder Lake, at the west end of the park road, and McLeod Lake, nine miles southwest of Wonder Lake.

In each watershed, researchers sampled snow, water, lake sediments, lichens, conifer needles, air, and fish. Air and vegetation were measured in 12 additional parks and national forests, and hunters in Alaska donated moose tissue to the project.

A thorough analysis

Each sample was analyzed for over 100 compounds, and in some cases, new laboratory techniques had to be developed to analyze project samples. The primary contaminants analyzed were semi-volatile organic compounds (SOCs) such as DDT and PCBs, and heavy metals such as mercury. These contaminants share the characteristics of persistence, bioaccumulation, and varying degrees of toxicity. Some of the manufactured chemicals found in Denali have been banned from use in North America, but are still used legally on other continents.

Key findings in Denali

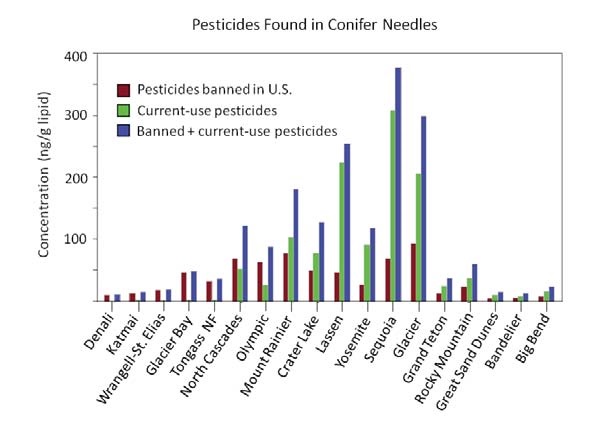

Most of the contaminants found in Denali vegetation, lake water, snow, sediments, and air were at relatively low concentrations. In general, Alaska samples contained lower concentrations of contaminants than samples from parks in the lower 48 states. (See graph at right for pesticides found in conifer needles.)

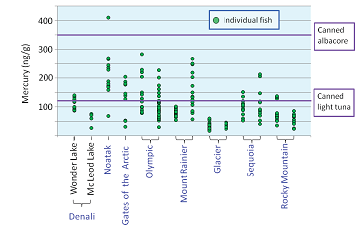

Concentrations of PCBs, mercury, and dieldrin—an insecticide banned in the U.S. in 1987—were higher than expected in some Denali fish, although none were at levels that exceeded human health standards established by the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. (For mercury results, see graph below.) Fish can accumulate contaminants in their tissues from their food and from the environment, so small inputs to ecosystems can be magnified over time in individual fish.

Wildlife species that eat mostly fish can be particularly sensitive to contaminants. Average mercury concentrations in Denali fish were above published thresholds for the health of kingfishers, mink, and river otters.

In contrast to fish, sampled moose tissues contained very low levels of contaminants, well below levels of concern for human consumption.

Putting it all in perspective

Results from the WACAP study show that Denali ecosystems, while still intact, are not entirely pristine. Bioaccumulation of contaminants in fish and wildlife species are of particular concern for subsistence users, because they typically eat more fish and wild meat than most other people. While the contaminant levels in some Denali fish were higher than expected, the fish from the two lakes sampled in Denali did not contain concentrations that would require even subsistence users to limit their consumption.

Science can make a difference

It is fairly certain that the persistent, toxic contaminants found in small amounts in Denali ecosystems do not primarily come from within this six-million-acre park. Their presence is an indication that airborne contaminants are transported to the park from afar. As global development continues to increase, the amount of airborne contaminants transported to Denali from international sources is likely to increase as well.

Regional and international efforts to reverse this trend can cite data collected in national parks, including Denali, to illustrate how contaminants released in one place don’t stay in one place. For example, in June 2010, EPA took action to end all use of the pesticide endosulfan in the United States, and referenced published data from the WACAP project to support its decision.

For more information, check out the Western Airborne Contaminants Assessment Project.

Last updated: July 28, 2016