NPS Photo / Kent Miller

“One back leg of a Dall’s sheep lamb. One arctic ground squirrel carcass. Some willow ptarmigan feathers. Four snowshoe hare legs. Another ground squirrel.” A wildlife biologist, who rapelled down the rock ridge to the untidy stick nest of a golden eagle, is calling out the various food items that are scattered around the perimeter of the nest. The field assistant records what the adult eagles have been feeding to their nestlings, and this tally becomes part of the growing data set on golden eagles in Denali National Park and Preserve.

Carol McIntyre, is the biologist, and she and her research colleagues have been asking and answering many questions about the nesting and migratory ecology of golden eagles at Denali since 1987. The tally of carcasses helps answer such questions as: What is the diet of golden eagles in Denali, and does it change appreciably from year to year?

Other questions that the researchers have posed include: In what kind of landscapes do eagles build their nests? What percentage of nest territories are occupied by pairs of golden eagles each year? How successful are golden eagles at producing eaglets? How do food supply and other factors affect golden eagle success at fledging young? How long do fledged young depend on their parents? Where do young eagles go when they leave Denali? How and where do sub-adult eagles spend their days before entering a breeding population?

McIntyre and her collaborators are also learning how the habits of Denali’s birds may be different from those of golden eagles that nest at lower latitudes. For example, while the nesting densities of golden eagles are higher in Denali than most other places this species has been studied, the reproductive success of eagles in Denali tends to be lower.

Learning About Golden Eagle Natural History

Early naturalist-scientists in the park, such as Charles Sheldon, Adolph Murie and Joseph Dixon, recognized that golden eagles were an important component of the region’s fauna—they observed the natural history of golden eagles in the park. They knew that these eagles build large stick nests on cliffs and rock outcrops (and McIntyre has probably visited some of the same nests they observed). They also knew that eagles lay one to three eggs in these unkempt nest-platforms, and usually one or two eaglets hatch in mid- to late May or early June.

They also knew that the nestlings fledged by mid- August, but did they know that the fledglings remain in the general nest area for four to eight weeks? During this time, the fledglings are dependent on their parents for food and protection from predators, and are exercising their muscles and practicing independent flight. Murie knew that golden eagles from Denali were migratory, but did he observe the 4-month-old eagles departing in late September or early October and realize that many of them would spend the winter as far south as central Mexico?

Building on the earlier observations of Murie and Dixon, McIntyre and her collaborators have learned many of the details of how golden eagles spend their lives in Denali and beyond the park’s borders. While some questions are newly posed, other questions have been answered as a result of more than two decades of research on golden eagles in Denali. Here are a few short summaries of research findings.

Selected Findings from Golden Eagle Research in Denali National Park and Preserve:

Landscapes Near Nest Sites

McIntyre and research colleagues described the landscape characteristics within the central core of 36 golden eagle nesting territories in Denali. Within that core—with a radius of 3000 m (10,000-feet)—there is a mosaic of alpine, upland, and riparian land-cover types represented. On average, the alpine low shrub types predominate (34%) followed by alpine barren (20%). The researchers hypothesize that building nests in open landscapes provides better opportunities for hunting.

Occupation of Nesting Territories

Golden eagles in Denali build nests on rock outcrops and cliffs. The nests range in depth from ~0.5 to 3 meters (1.5 to 10 feet). A nesting territory may have one or more nests. Since 1988, McIntyre and field crew have surveyed annually (by helicopter) nearly 80 nesting territories soon after egg laying in mid-April to find out if the nesting territories are occupied, i.e., the eagle pair is constructing a nest or incubating eggs. Nearly 90 percent of these territories are occupied each year.

Success at Fledging Young

Female eagles lay one to three eggs, and most eggs hatch by early June. McIntyre has studied several nesting-related variables in relation to availability of food.

From 1988 to 2010, laying rates (percentage of pairs with eggs) have ranged from 13 to 88 percent, and laying is closely associated with the abundance of snowshoe hares. During the same period, success rates (whether a pair produced a fledgling) have varied from 40 to 88 percent. Brood size averages 1.45 fledglings per successful pair. About one-quarter of the nests (27 percent) produced 50 percent of the fledglings from 1988-1999.

More eagles lay eggs and raise young in years when the snowshoe hare cycle is at its peak than at its low point. Snowshoe hares and willow ptarmigan are important spring food sources for golden eagles in Denali. Later in the nesting period, Arctic ground squirrels are also an important food source for golden eagles, but they are not available as prey until they come out of hibernation.

Post-fledging Dependence and Juvenile Survival

Most fledglings leave the nest by mid-August. After fledging, a juvenile golden eagle remains near the nest for 39 to 54 days and has a 94 to 100 percent chance of surviving to embark on its first autumn migration. The survival rate of juveniles raised in Denali has ranged from 19 to 34 percent; starvation is one of the primary causes for young eagle deaths.

Movements of Juvenile Golden Eagles

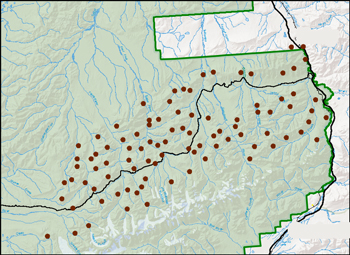

McIntyre and colleagues used satellite telemetry to study the year round movements of 48 juvenile golden eagles from 1997 to 2002. Juvenile golden eagles from Denali migrated south across the Rocky Mountains (peak movements during tail winds), arriving on their winter ranges from 31 to 86 days after leaving Denali in late September.

Juveniles returned to Alaska and

northwestern Canada in late May, many following a different route than the one they had used southbound. Their 24- to 54-day spring migration covered from 2,000 to 4800 km (1,200 to 3,000 miles). Eagles migrated mainly at midday when updrafts favor soaring-gliding flight. Rather than returning to Denali, the juvenile eagles wandered throughout southcentral, central and northern Alaska.

Last updated: December 15, 2016