NPS Photo

By mid-October in 2013, the vibrant colors of autumn were all but gone. Park staff had closed operations at Wonder Lake, Eielson Visitor Center, and the Toklat road camp, and the Denali Park Road was ready for winter silence under snow. On October 23, Brad Ebel and Tim Taylor, the park’s road supervisors at the time, headed west for a final check of road conditions. They drove no farther than Mile 38, near the western edge of Igloo Canyon, where their passage was blocked by a colossal pile of soil, gravel, icy mud, and clay, topped by a recent dusting of snow. A massive debris slide had crossed the road.

Immediate Actions After Debris Slide Discovery

When did the slide occur? The last confirmed day that someone had driven successfully past this point was October 12, so park staff were able to narrow the date of this event to a span of less than two weeks.

Park geologist Denny Capps and several other geologists drove to the site, while the park pilot and other staff flew above it, to photodocument the conditions, make measurements of the event, and attempt to determine its underlying causes and any specific trigger that set the debris slide in motion. Once staff determined the hazard was manageable, crews cleared the road October 25-28. They worked 12-hour days, with flood lights as needed, to avoid having a frozen mass at spring road opening.

NPS Photo

Dimensions and Features of the Slide

Blocks of permafrost the size of small houses, capped with soil from the thawed active layer above the permafrost, were dislodged from a steep hillside above Igloo Creek and spilled over the road and down into the floodplain of the creek. The slide measured 600 feet (180 m) long, 110 feet (35 m) wide, and up to 35 feet (11 m) thick.

Staff from the maintenance division initially estimated the volume of debris to be 30,000 cubic yards (23,000 cubic meters)—a typical small dump truck can carry nine cubic yards. When geologists calculated the volume from field measurements, the number was very close to the initial estimate.

The debris slide consisted primarily of cobbles, silt, and clay, which had been part of a frozen layer of unconsolidated sediments. The exact cause(s) and trigger of the debris slide remain unknown. However, permafrost may have thawed or thinned through a clay layer, causing the clay to become slippery and unstable. During this time, when day temperatures were near or above freezing, and nights dipped below freezing, water may have seeped into cracks in the permafrost and repeatedly frozen and expanded—triggering the debris slide. The massive frozen blocks slid downhill on the lubricated clay layer, and momentum carried them across the road.

Monitoring the Debris Slide

Will more debris come down in the same place? To address this question, park staff are collaborating with staff from the NPS Alaska Regional Office, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska Department of Transportation, and the Federal Highway Administration. The cross-disciplinary effort initiated three measures soon after the debris slide occurred, in order to track any future changes at that location:

- creation of an elevation model

- use of time-lapse photography in relation to rain gauge data

- frequent site visits

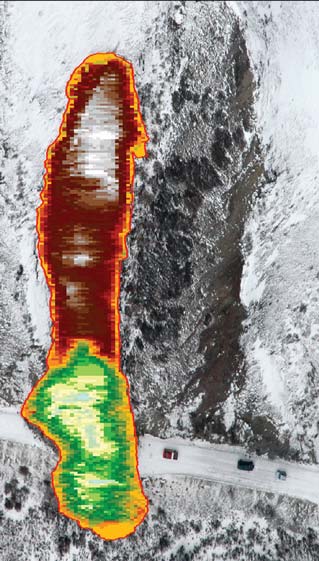

Soon after the slide, geologists mapped the area with precision GPS and built 3D digital elevation models (DEMs) showing the topographic conditions before and after the slide. The changes in elevation of the debris that resulted from the slide are mapped at left below. Park scientists can detect new slides by comparing future or recent DEMs to older ones and noting elevational changes. When combined with real-time weather, these elevational changes also can be used to assess the potential for future slides.

A camera was set up facing the slide, and time-lapse photography has been capturing the current state of the slide every five minutes, 24/7. Scientists can compile and analyze the photos as if they are a video, to detect the status of the slide (e.g., dormant, active, accelerating). They also can correlate the photo data with rainfall data collected at a nearby rain gauge to determine whether precipitation is significantly affecting slide activity.

NPS Photo

Will Similar Slides Occur Elsewhere?

To address the question of whether similar events likely will occur elsewhere along the road, the park initiated an assessment in 2014 to help analyze such potential hazards.

Many areas in Denali are prone to debris slides and other mass movements because they contain steep slopes and frozen sediment or soil layers that can thaw. Sometimes mass movements are gradual (over months or years) and sometimes massive blocks of material can detach and fall from a hillside quickly (in seconds or minutes). These processes occur in Denali, but, because of past and ongoing science and engineering efforts to ensure the safety of visitors and staff, relatively few large events have occurred along the park road.

Safety and Collaboration

As a basic precaution, staff placed road signs on either side of the debris slide to discourage buses and other traffic from stopping to look up at the slope where the debris slide originated (see photos above). However, the effort to monitor and mitigate the park’s geohazards, such as debris slides, goes beyond the placement of a few signs.

On one October day in 2013, Brad and Tim may have encountered a blocked road, but collaborative steps are taken every day to ensure that visitors and staff have continuous access to, and safe experiences on, Denali’s ribbon of road.

Last updated: October 26, 2021