Denali maintains a strong commitment to preserve and interpret not only the expansive natural resources of the park, but also a rich collection of historic and prehistoric sites that provide a record of over 10,000 years of human settlement and activity in an area frequently considered today as an “untouched wilderness."

The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations... NPS Mission Statement (2001)

These ancient and recent historic places are important because they provide a tangible link to the past. Once lost, these links can never be recovered. They are material touchstones to the past, providing learning experiences and connections that confi rm the reality of the past—people actually lived, struggled, laughed, and died here.

Each generation can learn from the lumps of ground where buildings stood, from ruins, restored buildings, and the objects of the past. These are the landmarks that provide linkages over time and space, and give perspective and added meaning to modern lives.

National Historic Preservation Act

In addition to the National Park Service’s stated mission of protecting and interpreting cultural resources, the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 is the legal framework of cultural resource preservation in national parks. The NHPA mandates that Federal agencies identify historic properties in their possession, and that those properties be considered prior to taking any actions which could harm them.

In practice, this means that Denali is responsible for identifying and evaluating its historic properties. Denali’s cultural resource staff work in consultation with the Alaska State Historic Preservation Officer and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to determine whether or not a historic property possesses “integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association with signifi cant historic persons or events, or possess the potential to provide information important to advancing knowledge of history or prehistory.”

If these criteria are met, than a property is determined eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), joining the ranks of other national historic treasures with this status. Under the law, this status of eligible provides them the same level of consideration as places that have been formally listed.

So far, Denali has several properties listed on the National Register:

- Teklanika Archeological District (1976)

- Mt. McKinley National Park Headquarters Historic District (1987)

- Park Patrol Ranger Cabins (multiple property documentation, with each Patrol Cabin listed individually in the NRHP).

Many historic and archeological sites, such as the Park Road, Savage Camp, Wonder Lake Ranger Station, many prehistoric sites throughout the park, and the Old Eureka / Kantishna Historic Mining District have been determined eligible for the National Register.

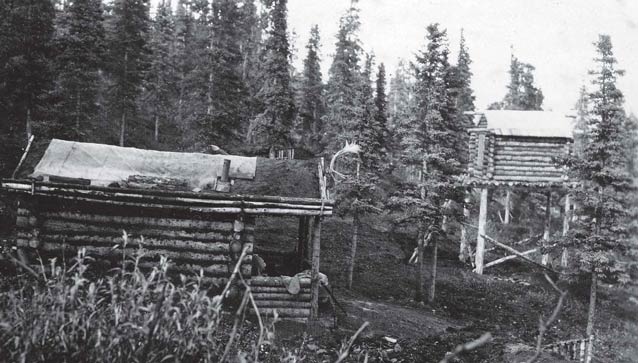

NPS Photo

Section 106 of NHPA

When the park is considering a project that could impact the integrity or setting of a historic property (e.g., new construction of road, trail, or building; a new installation proposed by a researcher, or the rehabilitation of a cabin), section 106 of the NHPA spells out a process for consulting with the State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO) and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

The consultation process is legally mandated, though the fi nal decision concerning the treatment of the property in question lies with the Superintendent of the park. The section 106 process has been applied numerous times in Denali over the years.

Three of the more visible projects subjected to 106 consultations in 2009 are the restoration of historic Ranger Patrol Cabins, the damage by informal trails to the remains of the park’s fi rst headquarters on Riley Creek, and the proposed construction of roadside pulloffs along the Denali Park Road.

Restoration of the Upper Toklat Patrol Cabin

Constructed in 1927 by park rangers as a relief cabin for backcountry patrols, the Upper Toklat Patrol Cabin (also known as the Pearson Cabin) serves much the same function today and is a “contributing member” to the Mt. McKinley National Park Patrol Cabins National Historic District.

The cabin was slated for rehabilitation in 2009 to ensure it would remain functional and continue to withstand the elements.

However, the rehabilitation necessitated replacing with modern materials some of the cabin’s “historic fabric,” which could potentially threaten its overall historic character.

After careful consideration and consultation, it was determined that the rehabilitation work, because it would be hidden from view, would not adversely impact the structure. Without the careful oversight of the 106 process, the historic character of this cabin, and of many others like it in Denali, would almost certainly be lost.

Protecting the Original Park Headquarters

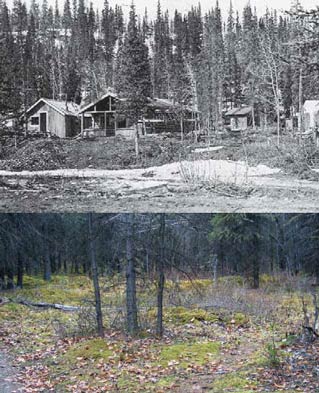

Little remains of the original park headquarters which occupied the bank of Riley Creek near the park entrance between 1921 and 1924.

Buried archeological ruins and foundations are all that is left at the site. Various social trails were threatening these archeological remains, so Denali cultural staff recommended that the trails crew construct an authorized path adjacent to the site to by-pass the historic remains.

The archeological survey mandated by the NHPA allowed the threatened portions of the site to be identifi ed, documented, and avoided during the trail construction in 2009.

Maintaining the Character of the Park Road

The Denali Park Road was built as a rustic one-lane dirt road by the Alaska Road Commission—in partnership with the NPS—between 1922 and 1938. It was designed to provide visitors and park rangers access to the interior of the park, as well as vehicular access to the Kantishna Mining District on the northwest edge of the 1917 park boundary.

The road has been continually maintained and somewhat altered from its original design, particularly during the Mission 66 Period in the park when the fi rst half of the road was widened and fi fteen miles were paved.

Nevertheless, today’s road retains the integrity of location, setting, feeling, association, and its basic alignment. It is enjoyed by modern visitors in much the way it was originally intended to be used. For these reasons, the Park Road was determined eligible to the NRHP in 2009. Park plans to modify the road by creating shallow pulloffs to facilitate two way traffc were carefully scrutinized by the NPS cultural staff and the Alaska SHPO using the section 106 process. Eventually, plans were developed that allowed the construction of the pulloffs without adversely affecting the historic feel of the road.

Thoughtful Consideration of the Past

The three projects mentioned here have been initiated or completed, but only after carefully evaluating their potential impacts on the historic sites. The section 106 process may sometimes seem excessive and drawn out, but 106 consultation is more than just a legal requirement. It is the vehicle that ensures proper and thoughtful consideration of historic properties in national parks. Without it, large-scale development or even small incremental modifi cations to historic properties could eventually destroy our tangible connections to the past.

Last updated: July 12, 2017