NPS Photo / Tim Rains

From 2000 until 2010, the State of Alaska prohibited wolf hunting and trapping in two areas bordering the park, the Stampede and Nenana Canyon Closed Areas, in order to protect two of the park’s three most-commonly viewed wolf packs. At the spring 2010 meeting of the Alaska Board of Game, the National Park Service submitted a proposal to extend the eastern boundary of the Stampede Closed Area. Instead, the Board of Game decided to eliminate both closed areas and allow hunting and trapping wolves in all areas bordering the park.

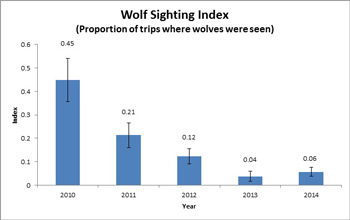

In 2010, Denali National Park and the University of Alaska Fairbanks, with the cooperation of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, began a study of wolf movements, wolf survival, and wolf viewing opportunities along the Denali Park Road.

This study is investigating a variety of factors that might influence sightings of wolves on the park road including;

- Wolf abundance

- Harvest of wolves outside of park boundaries

- Den location

- Pack size and composition(adults, pups, etc.)

- Individual behavior

- Pack social structure

- Pack proximity to the road

During the course of the study in 2012, the death of a breeding female from a pack that lived along the Denali Park Road was followed by a drop in wolf sightings. This was one of several instances where the death of an individual wolf, from legal trapping or hunting, sparked widespread media attention and concern in recent years. In order to improve our understanding of the implications of breeder mortality, we looked at changes in wolf pack fate, reproduction, and population growth following the death of breeders using data collected on 70 packs during the long-term study of wolves in Denali National Park. We published our findings in Journal of Animal Ecology:

Borg, B.L., Brainerd, S.M., Meier, T.J. & Prugh, L.R. (2015) Impacts of breeder loss on social structure, reproduction and population growth in a social canid. Journal of Animal Ecology, 84, 177–187

We found that breeder loss preceded or coincided with most documented cases of wolf pack dissolution (when a pack disbanded or was no longer found). However, the death of a breeding individual did not always lead to the end of a pack. In approximately two out of three cases where a breeder died, the pack continued. The sex of the lost breeder and the pack size prior to loss were important factors explaining pack fate following the death of a breeder as the probability of a pack continuing was less if a female died or if the pack was small prior to the death. The analysis also suggested that the death of a breeder had a greater influence if the wolf died during the pre-breeding or breeding season. Human-caused mortality rates were highest during the winter and spring, which correspond to the pre-breeding and breeding seasons for wolves such that harvest may lower the odds of pack survival because of this timing, especially when pack sizes are small.

However, higher rates of breeder mortality and pack dissolution did not correspond to lower population growth, indicating that the wolf population was resilient to the loss of breeding individuals at a population level. Wolves may compensate for the death of breeders in a variety of ways, such as rapid replacement of breeders or increased reproductive success the following year.

Last updated: March 29, 2016