Last updated: April 19, 2022

Article

White Spruce Cone Production and Seed Viability

By Sarah Stehn and Carl Roland (last updated April, 2022)

NPS Photo / Sarah Stehn

NPS Photo / Sarah Stehn

Results from this study indicate that spruce cone production occurs on approximately 3–4 year cycles, with climate conditions of the preceding years being the deciding factors in both seedfall and seed viability (Roland et al. 2014). For example, recent research from these plots suggests that an optimal cone production year will arise after two wet summers and low snow winters (during which reserves for cone growth are stored), followed by a warm and dry early summer (during which cones are initiated), and capped with a wet, cool summer just before seed dispersal (as cone maturation is complete).

However, high cone and seed production does not necessarily mean high seed viability since slightly different climatic factors control success of the two processes. Overall, the long-term mean annual germination percentage is only around 8% in the forest, and 5% at the treeline, indicating that it takes a white spruce tree quite a bit of energy, and perhaps luck, to successfully reproduce.

2022 Update

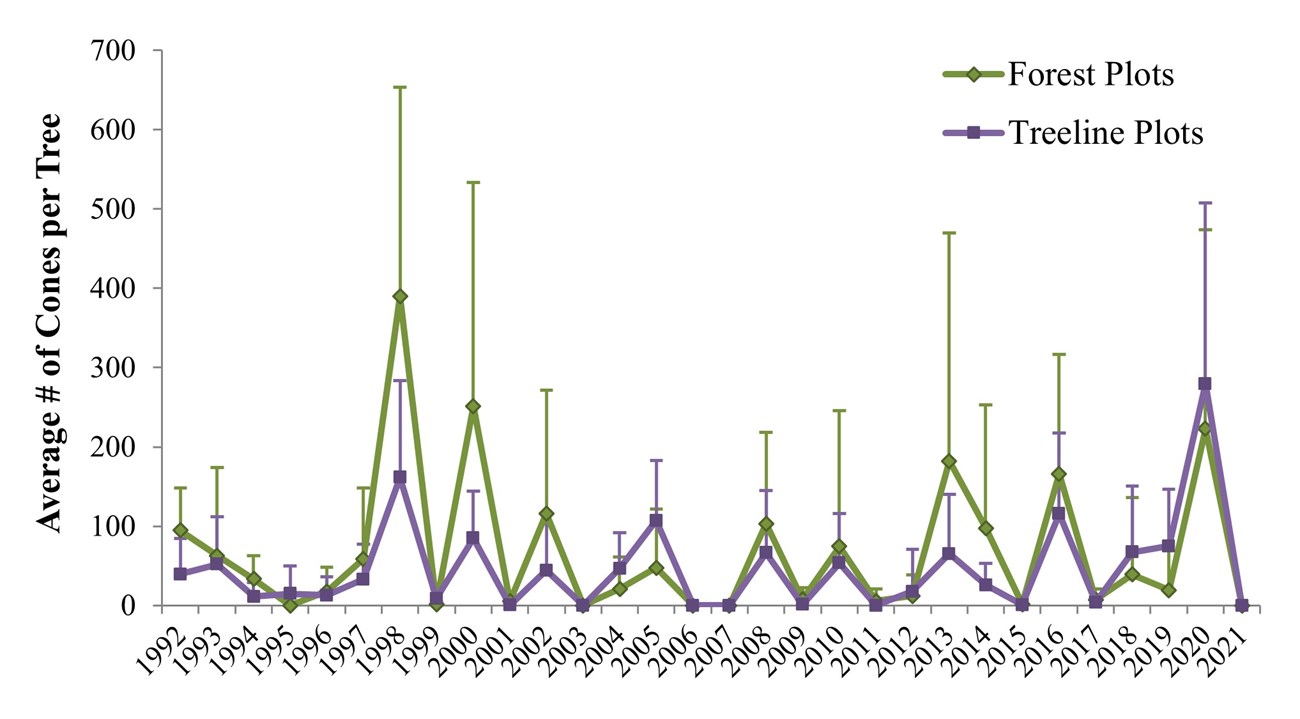

Cycles of spruce cone and seed production continue. Figure 4 illustrates that in 2021, spruce cone production was low, in fact, our study trees produced zero cones! They had good reason to take a break considering the banner cone production year of 2020.

Spring of 2020 was kind to Denali’s flowering plants, with large numbers of flowers observed in the much beloved pasque flower, aspen trees, and spruce trees! Beginning in mid-May, the lower branches of many spruce were laden with male pollen cones. These cones, bright reddish at first, elongate and turn yellow as they release their pollen in early June. By late June, one could observe the development of female seed cones, primarily found on the ends of white spruce’s upper branches near the tops of the trees. It is the female cones that most think of when envisioning of a spruce cone. Female cones are larger and more elongate (about 2 inches long) than the male cones. Early in their development they are light green, but turn purplish-brown by fall. As they mature and dry, seeds may be released and the color again changes—to a light brown.

Prior to 2020, the last notable cone production year, referred to as a ‘mast year’, occurred in 2016 (Figure 4). The highest cone production year in forest plots over the last 30 years was 1998, followed by 2000, and then 2020. At treeline, the pattern is a bit different, and 2020 produced the most cones by far! Interestingly, cone production at treeline has surpassed that in the forest only five out of the 30 years (in 2018, 2019, and 2020).

Spruce cone and seed production effects not only forest regeneration dynamics, but also likely contributes to the food supply for vole, squirrels and other small mammals, thus feeding into the predator-prey cycles of larger animals like eagles, hares and lynx. Monitoring of the white spruce reproduction plots will continue in 2022, adding to one of the longest-term records of white spruce seed production and viability in Alaska.

More Information

Roland, CR, Schmidt, J, and J. Johnstone. 2014. Climate sensitivity of reproduction in a mast-seeding boreal conifer across its distributional range from lowland to treeline forests. Oecologia 174: 665-677.