Last updated: December 2, 2019

Article

A Bear, Bacon, and a Dramatic Rescue 120 Years Ago

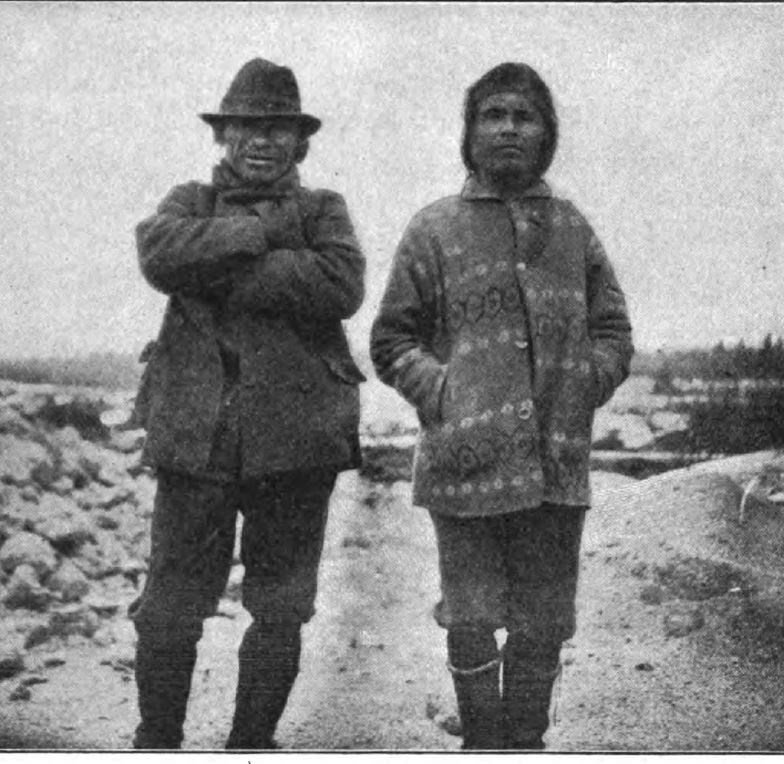

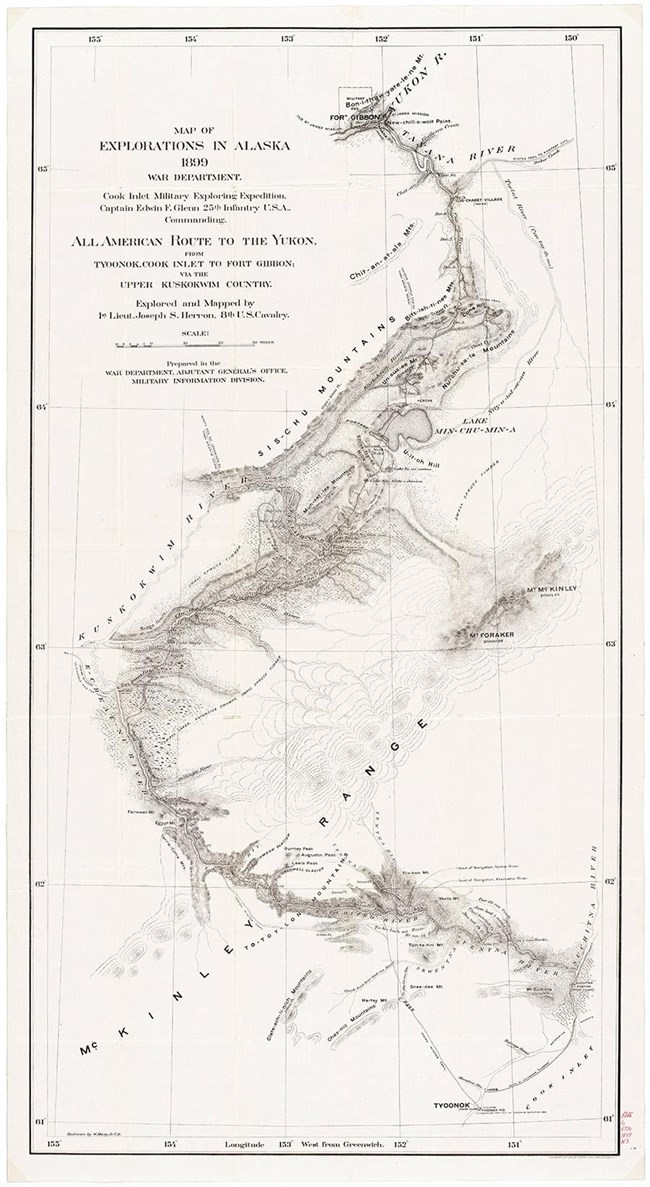

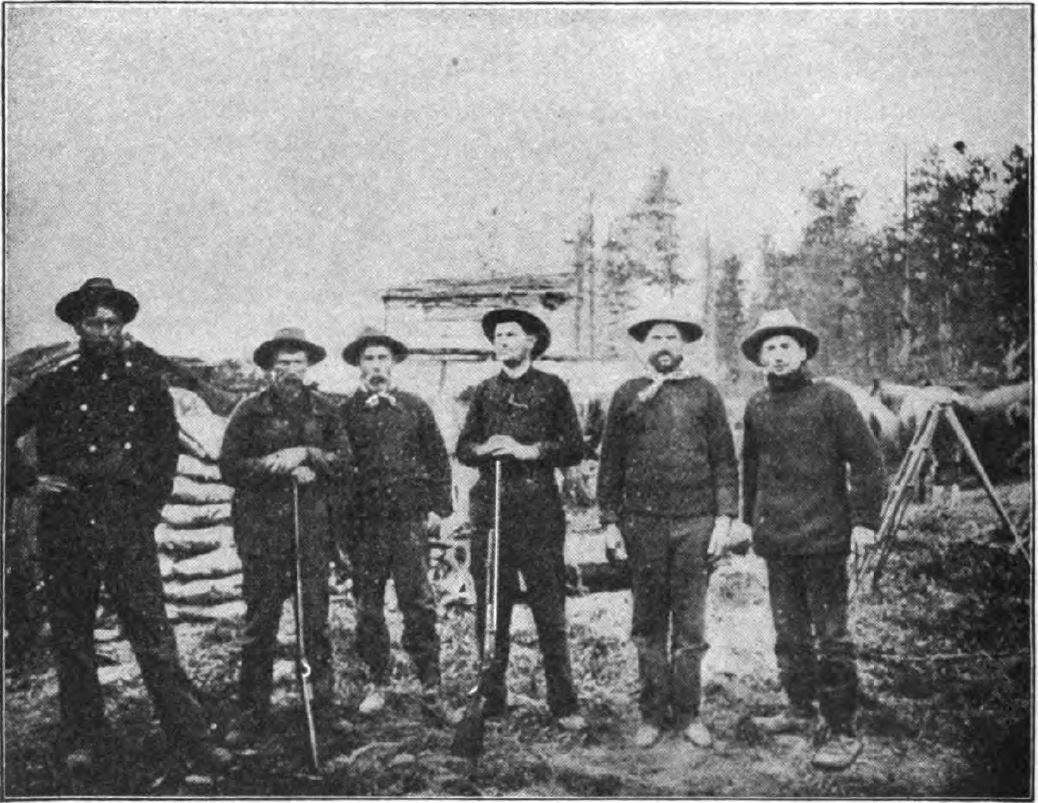

From Lt. Joseph Herron's publication "Explorations in Alaska," 1899.

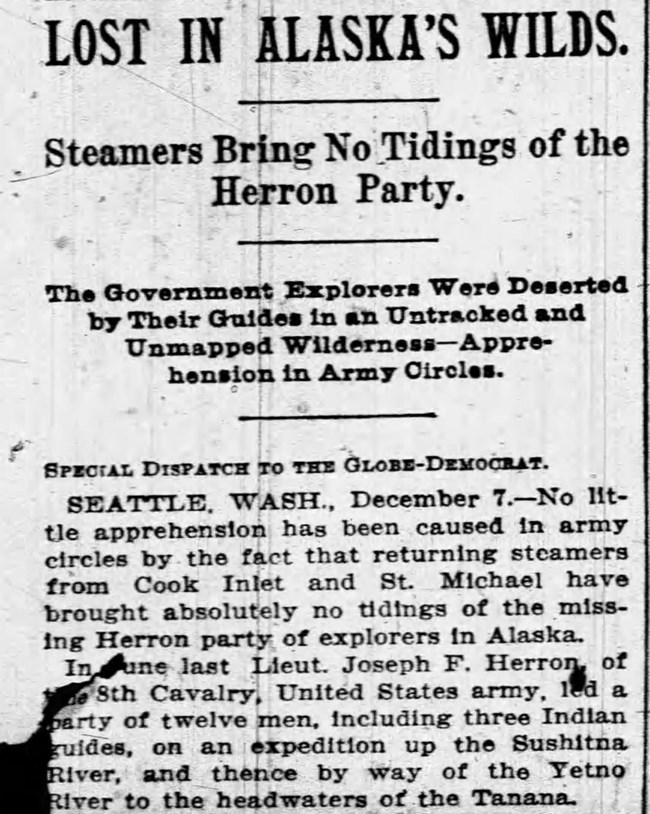

St. Louis Globe Democrat, December 8, 1899.

As legend has it, Sesui followed the bear tracks back to a raided cache, and eventually to Lieutenant Joseph Herron’s exploration party. The ill-equipped group were lost in the boggy lowlands on the northern slope of the Alaska Range (near the western boundary of what is now Denali National Park and Preserve).[1]

The Chief rescued the distressed explorers and led them to his village of Telida (Tilayadi). For over two months the Telida people helped the six strangers and provided them with warm clothing, food, and shelter to survive the oncoming winter for which they were not properly outfitted. When the conditions were again suitable for travel, Alaska Natives guided the expedition north on its final leg to Fort Gibbon (on the Yukon River at the mouth of the Tanana River).[2]

We were lost for three months, and ran entirely out of rations after wandering for several weeks with heavy packs on our backs. We had previously abandoned all of our faithful horses, and made rafts, but had to abandon them . . . . We were finally picked up in the mountains by a lone Indian, his name is Shesawy [Sesui], and he belongs to the Kuskokwim tribe. He took us to his hunting tent, twenty-five miles from where he found us. We remained with him sixty-five days and lived on dried fish and little moose meat. At this camp were four Indians and their families . . . . They were more than kind to us, and gave us everything they had.[3]

This article appeared in the Seattle Post Intelligencer on February 24, 1900.

US Exploration of Alaska at the Turn of the 20th Century

At the end of the 19th century, the United States government was conducting extensive surveys of Alaska. Alaska Natives often served as guides and provided the expeditions valuable local knowledge, and often sacrificed much to help strangers. Without this support, many of these expeditions would have failed. In the case of the Herron party, adding six men to the village of seventeen for two winter months would have been a tremendous resource burden. Gara Sesui (also known as “Carl”) mentioned how much his father had given to the men, and how little his people had received in return.

One hundred and twenty years after Herron’s party was saved, the Telida Village and people are still here, and are an important part of Denali National Park and Preserve’s community. Telida Village is a federally recognized tribe that park managers consult with regularly. An overview of Telida’s history is available in Ray Collins’ Dichinanek’ Hwt’ana.

From Lt. Joseph Herron's publication "Explorations in Alaska," 1899.

[1] Coincidentally, Sesui served some of the bacon-eating bear to the explorers. Years later, Chief Sesui’s son mentioned that evidence of horse tracks alerted the tribe to the presence of outsiders. See: Land Use in the North Additions of Denali National Park and Preserve: An Historical Perspective, by William Schneider, Dianne Gudgel-Holmes, and John Daile-Molle. Anchorage, AK: National Park Service, 1984, p. 72.

[2] The Telida Village site where the rescued party camped on the Swift Fork is several miles upstream from where the tribe’s most recent village is located. The village is used seasonally by tribal members. The Telida Village is a band of the Dinak’i (pronounced “dee na kee;” or Upper Kuskokwim (anglicized version) language group.

[3] This account appeared in the Seattle Post Intelligencer on Feb 24, 1900.

[4] Explorations in Alaska, 1899 gives a first-hand account of Herron’s travels in Alaska and provides insight into the colonial mindset the US government had toward Alaska Natives. Herron’s records also documented numerous Alaska Native place names and noted details about the 17 people in Telida at the time (p. 47-48 of Dichinanek’ Hwt’ana).

[5] Herron, who was from Ohio, named Mount Foraker (for Ohio Senator Joseph Foraker).