Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Article

Democracy Limited: The Politics of Dress

https://embed.culturalspot.org/embed/exhibit/dQLitXejg0YgLw?position=14%3A0

“Fashion is part of the daily air and it changes all the time, with all the events. You can even see the approaching of a revolution in clothes. You can see and feel everything in clothes.” —Diana Vreeland

What did the suffragists wear? Why did it matter?

The politics of dress are the ways that people use clothing to affect how they are perceived and treated. Suffragists understood the importance of how they and their cause were viewed in mainstream society. Previous attempts to argue for “dress reform”—that women should wear less restrictive clothes, or even pants—had caused controversy that many suffragists believed they could not afford. Even Alice Paul and more confrontational activists decided to avoid the scandal that wearing pants or figure-fitting clothing would cause. Instead, suffragists used fashion to gain mainstream support for their cause.

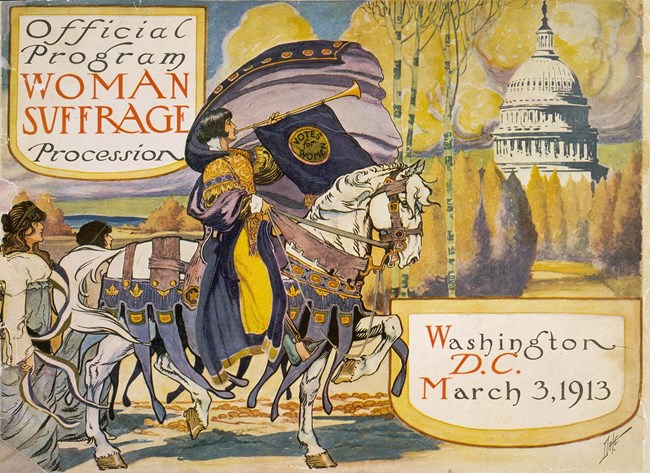

The white dresses and gowns worn in the Suffrage Procession of 1913 were part of their political statement for the cause. In contrast to the smart shirtwaists or formidable skirt-suit outfits sported by many university students and working women, women protesters donned pure white accented by purple and gold sashes. The full-length white dresses presented them as proper and “pure” women, a contrast to the negative caricatures of masculine women in pants that many people associated with the suffrage movement. The long dress adhered to modesty standards and the white represented a maternal and spiritual innocence expected of white, upper-class womanhood. Suffragists chose the sash colors because of their positive associations for both the suffrage cause and women. Purple represented loyalty to the United States and its democracy, important for suffragists to emphasize to combat the idea that women were rebelling against their husbands, country, and proper societal role. Yellow, meanwhile, was the color of hope.

When picketing outside the White House, suffrage protesters wore black as a visual display of their feelings. When they were arrested, their protest clothing and the message it signified were stripped away and replaced with a prison uniform. The rough prison garb was plain and reused, usually not washed between prisoners.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000249).

How did the Prison Special use the politics of dress?

Suffragists who had been imprisoned did not let the uniforms they were forced to wear stifle their message. In fact, they used the politics of dress in new ways. When suffragists appeared in public on the Prison Special, they wore replicas of the clothes they’d been forced to wear in prison. Though still dresses, the prison uniform violated the idea of appropriate clothing for middle-class white women in the early twentieth century. The dresses were thin and straight-cut in a way that would have been scandalous had the women chosen them for themselves. Audiences watching the suffragists wear their prison uniforms generally viewed the fact that the prisons had put the women in such clothing as reflecting negatively on the political system. How could women put their trust in a government that would disgrace them in such a way? The message of the Prison Special was that women needed the right to vote to protect their dignity from government abuses.

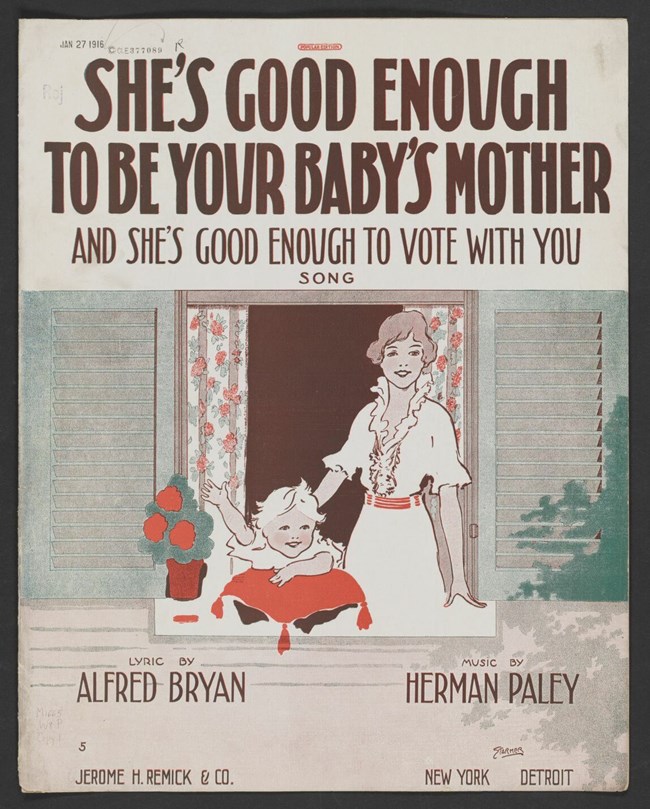

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2017562275).

Why were the Prison Special’s clothing choices impactful?

The fashion choices of these suffrage activists were effective because they spoke to the public in a way that they would understand. Highlighting their loyalty combatted the belief that all women in the suffrage movement wanted to overthrow the United States government or force men to take on feminine roles. These suffragists were constantly careful about how they presented themselves and tried to make sure the attention they received was in favor of their cause. The Prison Special highlighted how the government without women’s votes was harmful to women by showing how it violated social rules of female modesty. The success of the Prison Special relied on the unofficial politics of dress to make the argument that women not only deserved the right to vote but actually needed it in order to be virtuous women.

Bibliography

Blackman, Cally. "How the Suffragettes Used Fashion to Further Their Cause." Stylist. https://www.stylist.co.uk/fashion/suffragette-movement-fashion-clothes-what-did-the-suffragettes-wear/188043.

"Fashioning the New Woman: 1890-1925." Daughters of the American Revolution. https://www.dar.org/museum/fashioning-new-woman-1890-1925-0.

Kelly, Katherine Feo. "Performing Prison: Dress, Modernity, and the Radical Suffrage Body." Fashion Theory 15:3, 299-321. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174111X13028583328801.

The Morgan City daily review. (Morgan City, La.), 18 Feb. 1919. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88064293/1919-02-18/ed-1/seq-1/.

O'Brien, Alden. "Great Strides for the "New Woman," Suffrage, and Fashion." National Museum of American History, March 7, 2013. https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2013/03/guest-post-great-strides-for-the-new-woman-suffrage-and-fashion.html.

by Brianna Nuñez-Franklin

Last updated: May 21, 2020