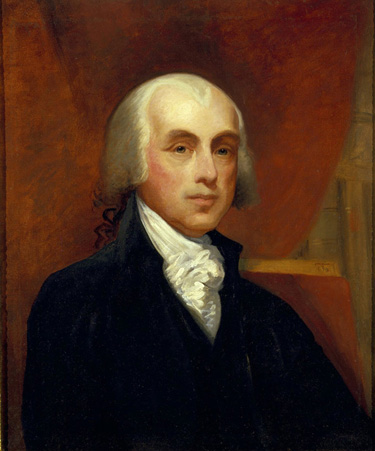

It was known as Mr. Madison’s War. Throughout his career James Madison was appreciated for his deliberative character, his leading role in state and national legislatures, and his reasoned opinions on such issues as commerce and constitutions. But no one looked to the guarded, if good-humored, fourth president for wartime leadership.

"Who will be the next President causes great doubt, / As all parties agree whiffling Jemmy goes out." Opposition to James Madison published in the Alexandra [Virginia] Gazette

Republicans Ascendant

NPS

Unlike his Princeton contemporaries Colonel Aaron Burr and General Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee (the father of Robert E. Lee), James Madison was not a man of action and had never been eager to enter the field of battle. Slight of build, sickly and short, he was nicknamed “Little Madison,” and to those who willfully mocked him, “Little Jemmy.” Even after having served for eight years as Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of state, respectful and sympathetic members of his own Republican Party suspected that President Madison was not temperamentally equipped to lead the nation through a second war with Great Britain.

In 1809, as Madison succeeded Jefferson, the Republicans (also known as Democratic-Republicans) were in the ascendant. Much had changed in twenty years. When George Washington took the oath of office in 1789, formal political parties did not yet exist. Supporters of the new, relatively strong central government were Federalists; those who remained suspicious of centralized power and pressed for a Bill of Rights to explicitly protect individuals against federal encroachment were Antifederalists. But these designations indicated ideological differences not regular organizations.

During Washington’s first term, however, Madison and Jefferson saw danger to the republic in Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s power-engrossing measures. The two Virginians feared an executive that would come to imitate the British government and sacrifice republican principles. Despite Madison’s crucial work in defining the federalist system in 1787–1788, he, along with Jefferson and others, absorbed former Antifederalists and critics of the administration into what became the Republican Party. Washington administration stalwarts retained the name Federalists; their last successful presidential nominee was John Adams, and they would be politically defunct by 1815. In Andrew Jackson’s time, the Jeffersonian-Madisonian Republicans were known as Democrats and are thus ancestors of today’s Democratic Party—not the Republican Party formed in 1856 to which Abraham Lincoln belonged.

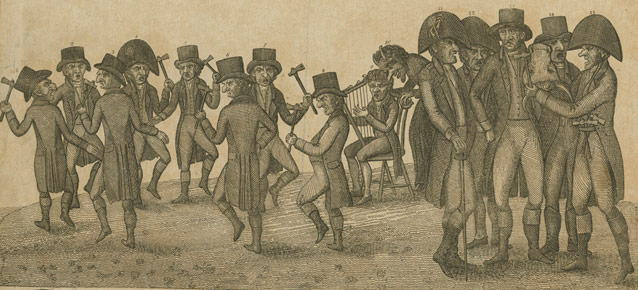

The Federalist Challenge

Maryland Historical Society

The Federalists did not go down easily. From the moment Madison succeeded Jefferson, they were public in their denunciations of the new Republican president. And in the run-up to war, as Madison sought reelection, the opposition Alexandria [Va.] Gazette published a nasty piece of doggerel: “Who will be the next President causes great doubt, / As all parties agree whiffling Jemmy goes out.” In the vocabulary of the day, to whiffle was to waver. As the saying goes, though, one should not judge a book by its cover. Yes, Madison was a bookworm; but he was also an ardent nationalist keen on American expansion and confident in his ability to conduct the coming war. He was not a whiffler.

In 1810, midway through his first term, Madison had turned his attention to the Gulf of Mexico, deftly managing the acquisition of West Florida from Spain, while making it known that he was interested in annexing East Florida as well when that became feasible. Spain was militarily weak, unlike England. Madison dreamed of incorporating Canada as well as Spanish Cuba into the expanding Union, but the United States was not strong enough to advance its aims through bluster, and the fiscally conservative Republican president was initially unprepared to spend adequately on national defense.

Instead, he looked for ways to pressure London to back down from its bullying on the high seas. The 1807 Orders in Council, which threatened all neutral shipping, had not been rescinded. Early in his presidency, Madison assured his predecessor that he would stand strong, with “a prudent adherence to our essential interests.” By April 1812, he had determined that the British “prefer war with us, to a repeal of their Orders in Council. We have nothing left therefore, but to make ready for it.” The retired Jefferson thoroughly concurred.

Part of a series of articles titled Madison, Party Politics and the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015