Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

Decatur House: A Home of the Rich and Powerful (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

From its beginnings in 1819 as the home of a wealthy naval hero, Decatur House—on Lafayette Park across from the White House in Washington, D.C.—has served as an elegant setting for social gatherings. Presidents, ambassadors, senators, congressmen, and other influential people gathered to listen to the gentle sound of their hostess playing the harp, gossiped about those who were not present, or engaged in hushed conversations about the rise or fall of the fortunes of other guests. Ambitious guests often used social events at Decatur House as a means to affirm their own power and influence in Washington.

Stephen Decatur's mansion reflected the importance that the politically ambitious once placed on being in close proximity to a site of authority—in this case the president's house. For more than 130 years, Decatur House was the coveted residence of individuals seeking political or social influence. Today, the National Trust for Historic Preservation operates Decatur House as a museum.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file for Decatur House (and photographs) and related materials prepared by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which preserves Decatur House as a historic house museum. It was written by Robin Fogg Schuldt, former Curator of Education for Decatur House Museum. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in units on the early national period, including the War of 1812 and the growth of the federal city. It examines the life of Stephen Decatur, a naval hero who died as a result of a duel in 1820, and considers the role the house he built played in the political and social scene of the nation's capital up to the 20th century.

Time period: Early 19th century to early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Decatur House: A Home of the Rich and Powerful relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801 to 1861)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands the international background and consequences of the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Monroe Doctrine.

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the first era of American urbanization.

-

Standard 3A- The student understands the changing character of American political life in "the age of the common man."

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Decatur House: A Home of the Rich and Powerful relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G- The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

- Standard J - The student observes and speculates about social and economic effects of environmental changes and crises resulting from phenomena such as floods, storms, and drought.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

- Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing interactions of individuals and social groups.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

1) To examine the practice of dueling in early 19th-century America.

2) To explain the significant role the Decatur House and its residents played in the social and political life of Washington, D.C. during the 19th and 20th centuries.

3) To examine the process of gaining access to politicians at the state and local level.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) one map and drawing of Lafayette Park and its surroundings;

2) four readingsthat describe Stephen Decatur's rise to fame and fortune, his early death, and the subsequent history of the house he planned and built;

3) one historical painting and photo of Decatur House;

4) floor plans of Decatur House.

Visiting the site

Decatur House is a museum property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The house is located at 748 Jackson Place, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006. It is within easy walking distance of Farragut West and Farragut North Metro stations. The house is open Tuesday-Friday, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., Saturdays and Sundays, noon to 4 p.m. It is closed on Mondays, New Year's Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. For additional information, visit the Decatur House web page.

Setting the Stage

In a series of complicated debates and compromises over the assumption of the states' Revolutionary War debts by the newly-created Federal Government, a diamond-shaped portion of land carved from the states of Maryland and Virginia became the District of Columbia. This site of the federal city of Washington stretched along the marshy shores of the Potomac River. Few people thought the site could ever become a great capital city. Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, called it "the very dirtiest Hole," its streets a "quagmire after every rain." Senators and congressmen spent as little time as possible in Washington, often renting single rooms from one of the hotels or boarding houses near the Capitol building during the short terms of Congress. Those few government employees who worked year-round had little to do but collect tariffs, order the defense of the nation's borders, and deliver mail. Even they did not feel like settling in, because they believed it was highly possible that the capital might again be moved.

Conflicts abroad soon caused the government to grow. First, the country needed a navy to protects its trading interests against the Barbary Pirates of North Africa. Then the War of 1812 required additional growth of the navy and the army. With more governmental activity and responsibility, the city of Washington began to attract important and ambitious men. Among the new residents was Stephen Decatur, hero of the war with the Barbary Pirates and the War of 1812.

When the new government had purchased land for the president's mansion in 1792, it planned that the land on either side of President's Park, later renamed Lafayette Park, would be used as lots for private homes. For many years, the land lay vacant. When Decatur decided to build his home near the White House, however, others followed his lead, and the landscape of Lafayette Park began to take shape.

The conspicuous site chosen by Decatur was consistent with his military prominence and his public esteem. To design the house, he hired Benjamin Henry Latrobe, America's most prominent architect. This first private residence on President's Park was planned and built to be a place for sparkling entertainment in a city that was hungry for social occasions, and where social contacts played a central role in obtaining power and influence.

Locating the Site

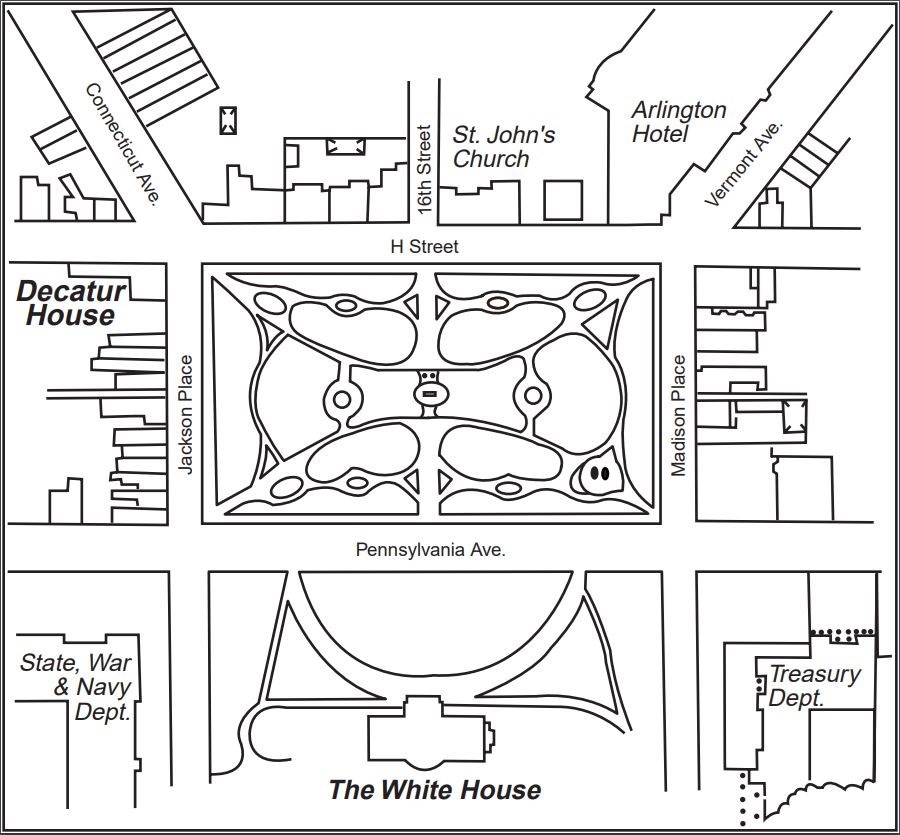

Map 1: Lafayette park and its surroundings, 1891.

Former or present residents of Lafayette Park as of 1891 included: Reverdy Johnson, senator and minister to England; James Buchanan; Benjamin Harrison; the Prince of Wales; William L. Marcy, secretary of war and secretary of state; Lewis Cass, secretary of war and secretary of state; Senator Pomeroy; Lord Ashburton; John Hay, poet and historian; Henry Adams, author; Walter A. Wood, inventor and manufacturer; Daniel Webster; Admiral Shubrick; Judge Bancroft Davis, secretary of state and minister to Germany; Commodore Stephen Decatur; Henry Clay; Martin Van Buren, vice president; John Gadsby; George M. Dallas, vice president; General Beale; Senator James G. Blaine; Charles Glover, banker; Commodore Stockton; General Daniel E. Sickles; Peter Parker, minister to China; James Madison; Dolley Madison; General McClellan; William Windom, secretary of the treasury; Senator Don. Cameron; Henry Clay; John C. Calhoun, vice president; and William H. Seward, secretary of state.

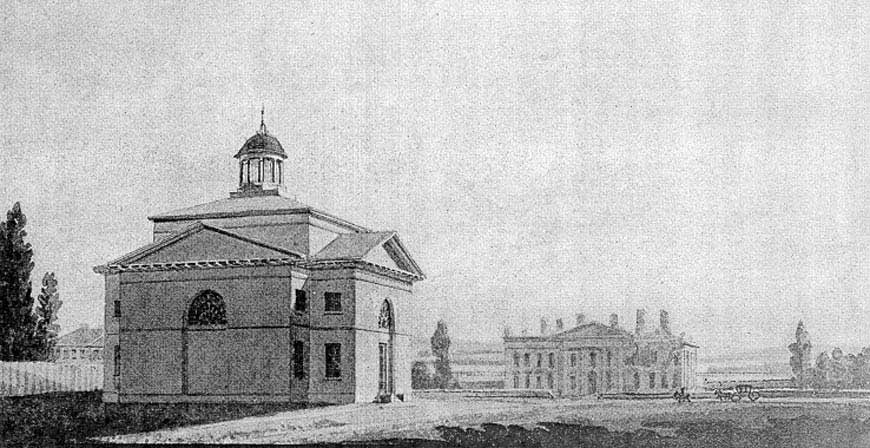

Drawing 1: Benjamin Latrobe's 1816 drawing of

President's Park.

Drawing 1 is a view of St. John's Church and the presidents' house in 1816, before Decatur House was built. In June 1818, Stephen Decatur bought 19 lots on President's Park. In consultation with Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the finest and most fashionable architect of the era, he chose to build his home on the most prominent of the lots. He decided that the site across the street from the northwest corner of the open park would provide a perfect view of the president's house and an unobstructed path to the newly-built St. John's Church. He planned to hold the other lots to sell when the price of property went up.

Questions for Map 1 and Drawing 1

1. Locate St. John's Church, the White House, and Decatur House on Map 1. How had the park and area around it changed between 1816 and 1891?

2. What kinds of occupations were held by the people who lived on Lafayette Park? Does the list help you understand the attraction Lafayette Park held for well-connected, influential people? What names do you recognize from the key?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Stephen Decatur, A Nation's Hero

Born in 1779 to a prominent Philadelphia family, Stephen Decatur was reared in the traditions of the sea. His father had been a successful privateer during the American Revolution and assumed command of a naval vessel when the official American navy was established in 1798. At the same time, young Stephen Decatur embarked as a midshipman aboard the new frigate United States. It took him only a year to be commissioned as a lieutenant.

Decatur's first real act of heroism came during the Barbary Wars of 1801-1804. For decades the North African states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli had seized ships, crews, and passengers all over the Mediterranean Sea and held them for ransom. European nations avoided such incidents by paying an annual sum of protection money, or tribute. Both Presidents Washington and Adams had followed that custom, but President Jefferson balked at the idea. Tripoli declared war on the United States in May 1801, and Jefferson sent a naval squadron to the Mediterranean. The war dragged on with few victories for either side. Then in 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur performed a bold act. Under cover of darkness, he and 10 sailors slipped into Tripoli Harbor and set fire to the captured U.S. frigate Philadelphia guaranteeing that the ship could not be used by the Tripolitans against the Americans. His feat earned him a promotion to captain, and also the praise of Lord Nelson, England's greatest naval hero, who proclaimed it "the most bold and daring act of the age." The deed has been memorialized by the phrase in the Marine's Hymn: "to the shores of Tripoli."

During the War of 1812, Decatur and his men captured the British ship Macedonian, and brought her back as a prize to the safe shores of the United States. In 1815 Decatur commanded a squadron to Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli where he secured agreements forever ending U.S. payment of tribute to the Barbary States. After both triumphs, Decatur's exploits were widely described in newspapers. Greatly admired for his courage and cleverness, Decatur was honored with public dinners in New York and Norfolk, and presented with gifts of silver from Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Until the mid-19th century, captors of enemy vessels were entitled to receive a portion of the proceeds earned from the sale of the cargoes of captured ships. Decatur accumulated quite a generous sum through his exploits. With this prize money in hand, and with his appointment as a Commodore who would serve on the Navy Board of Commissioners, Decatur and his wife Susan came to Washington in 1816. Many people were eager to entertain the Decaturs, holding celebration dinners in the hero's honor. The reciprocal parties and dinners the Decaturs gave after they built their mansion on President's Park initiated the tradition of Decatur House as a focal point for Washington society.

The Commodore's reputation was that of a man with an engaging personality and good conversation. His wife charmed their guests with her intellectual achievements and her talent in playing the harp. Both were excellent hosts, and a party at Decatur House was always considered a notable event.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What actions made Stephen Decatur a national hero?

2. How did he become wealthy?

3. Why did Decatur settle in Washington and build his stately home there?

Reading 1 was adapted from Royana Bailey Redon, "Commodore Stephen Decatur," in Decatur House, edited by Helen Duprey Bullock (Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1967) pp. 39-46.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: A Conflict of Honor

As one of his earlier duties in the navy, Stephen Decatur had sat as one of the judges on the trial, or court martial, of Commodore James Barron. In 1807 Barron and his crew aboard the frigate Chesapeake encountered the more powerful British ship Leopard off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia. Finding his ship under attack with only one gun in place, Barron surrendered, and the British boarded his ship and seized four supposed deserters. The Chesapeake returned to Norfolk in humiliation, and the nation was furious.

In spite of a long and close friendship with Barron, Commodore Decatur agreed with the rest of the court that Barron had been at fault in the incident for failing to attempt appropriate defensive measures. Barron, who was expelled from the navy for a period of five years, was outraged that his old friend had agreed to the verdict.

When the War of 1812 began, Commodore Barron was overseas and just completing his five years of exile from the navy. He decided not to return to help defend his country. When Barron finally returned to the United States in December of 1818, he and Decatur were spoiling for a fight. Barron believed that Decatur was slandering his name in all of Washington, causing his "honor" to be destroyed. Decatur, for his part, criticized Barron's apparent lack of loyalty during the War of 1812. Barron claimed that he had no money and could not get back to this country. Back and forth over several years, the men exchanged letters. Eventually, the quarrel exploded into a battle of honor.

At this time it was not uncommon for men in public positions to challenge one another to a duel. Although dueling was outlawed in the District of Columbia, an unofficial "dueling ground" in nearby Bladensburg, Maryland, was used for many such illegal challenges. On March 22, 1820, Commodore Stephen Decatur and Commodore James Barron met on that field. Both men were shot, but Decatur was mortally wounded and died several hours later at his home on Lafayette Square.

At the height of his fame, and still ascending within the navy bureaucracy, Decatur gave up all for what he believed was an essential battle, a battle for his honor. The nation was distraught. People everywhere wept openly over the death of a favorite hero. John Quincy Adams, who attended the funeral, noted in his diary:

There were said to be ten thousand persons assembled ....The procession walked to Kalorama [a section of Washington where Decatur's tomb was located]....A very short prayer was made at the vault by Dr. Hunter, and a volley of musketry from a detachment of the Marine Corps closed the ceremony over the earthly remains of a spirit as kindly, as generous, and as dauntless as breathed in this nation, or on this earth.1

Susan Decatur left the house, moving to another section of Washington, and later entered a convent where she died in 1855.

Questions for Reading 2

1. Why were Decatur and Barron at odds with one another?

2. Why did their quarrel escalate into a duel? What was the result of that duel?

3. How does the quotation from Adams' diary help you to understand the high regard people had for Decatur?

Reading 2 was adapted from Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Courtland Van Dyke Hubbard, Historic Houses of George-Town & Washington City (Richmond, VA: The Dietz Press, Incorporated, 1938) pp. 259-262.

1As quoted in Eberlin and Hubbard, p. 262.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: To Duel or Not to Duel

Following are excerpts from several letters exchanged between Commodores Barron and Decatur in the months before their duel:

Barron to Decatur, June 25, 1819

If you were in my place you would have written as I have. Several gentlemen in Norfolk told me that such a report was in circulation, but could not now be traced to its origin. Your declaration, if I understand it correctly relieves my mind from the apprehension, that you had so degraded my character as I had been induced to allege.

Decatur to Barron, June 29, 1819

I meant no more to disclaim the specific and particular expression to which your inquiry was directed, to wit, that I had said that I would insult you with impunity. As to the motives of the 'several gentlemen of Norfolk,' your informants, and their informants, or the rumors 'which cannot be traced to their origin,' on which their information was founded, or who they are, it is a matter of perfect indifference to me, as are also your motives in making such an inquiry upon such information.

Decatur to Barron, October 31, 1819

I do not think that fighting duels, under any circumstances, can raise the reputation of any man, and have long since discovered that it is not even an unerring criterion of personal courage. I should regret the necessity of fighting with any man; but, in my opinion, the man who makes arms his profession is not at liberty to decline an invitation from any person who is not so far degraded as to be beneath his notice. Having incautiously said I would meet you, I will not consider this to be your case, although many think so; and if I had not pledged myself, I might reconsider the case.

Barron to Decatur, [date is missing] 1819

Upon this subject of dueling, I perfectly coincide with the opinions you have expressed. I consider it as a barbarous practice which ought to be exploded from civilized society. But sir, there may be cases of such extraordinary and aggravated insult and injury received by an individual as to render an appeal to arms on his part absolutely necessary. You have hunted me out, have persecuted me with all the power and influence of your office;...and for what purpose or from what other motive than to obtain my rank, I know not.

Decatur to Barron, December 29, 1819

If we fight, it must be of your seeking. I have now to inform you that I shall pay no further attention to any communication you may make to me, other than a direct call to the field.

Barron to Decatur, January 16, 1820

Whenever you will consent to meet me on fair and equal grounds, that is, such as two honorable men may consider just and proper, you are to view this as that call.

The Agreement to a Duel

On March 8th, 1820 both men signed the following agreement:

It is agreed by the undersigned, as friends of Commodore Decatur and Commodore Barron, that the meeting, which is to take place between the said Commodore Decatur and Commodore Barron, shall take place at 9 A.M., on the 22nd inst., at Bladensburg, near the District of Columbia, and that the weapons shall be pistols; the distance, eight paces or yards; that previous to firing, the parties shall be directed to present, and shall not fire before the word 'one' is given, nor after the word 'three'; and that the words 'one, two, three' shall be given by Commodore Bainbridge.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What attitude did both men seem to have about the practice of dueling? Were their thoughts consistent with their actions?

2. Based on these excerpts, do you think Decatur or Barron provoked the duel? On what do you base your opinion?

3. Do you think the duel was inevitable? Why or why not?

Reading 3 is excerpted from The Friends of Commodore Decatur, Correspondence Between the Late Commodore Stephen Decatur and Commodore James Barron Which Led to the Unfortunate Meeting of 22 March, 1820 (Washington, D.C: Gales and Seaton, 1820).

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: Decatur House Lives On

Although Decatur lived in the home he built in Washington, D.C. for only a year, it continues to be called by his name. As one of his biographers noted in 1938, "Stephen Decatur was one of the most romantic characters in American history...From the year of his birth down to that of his untimely death, a romantic glamour rested upon him. Like a faint, lingering odour of incense, an abiding trace of that glamour still attaches to the house he built."1

From 1820 until 1836, Susan Decatur rented the house to a long series of important political figures. Her first tenant was Baron Hyde de Neuville, the French minister and consul-general to the United States. The Baron and Baroness were very hospitable people, much given to entertaining, which they did exceedingly well. The next tenant was Baron de Tuyll, the Russian minister, who did not entertain as much as his brother diplomats, but who did give excellent dinner parties. On Washington and food, he commented, "Washington, with its venison, wild turkeys, canvas-backs, oysters, terrapins, &c., furnishes better viands [foods] than Paris, and only wants cooks."2

During the presidency of John Quincy Adams, the house was rented to Secretary of State Henry Clay, a prominent Whig and three times an unsuccessful candidate for president between 1824 and 1844. In the winter of 1828 a Washington resident wrote, "Mrs. C— is overwhelmed with company, besides a very large dining company every week and a drawing-room every other week. She says when Mr. C dines at home, he never dines alone but always has a social company in a family dinner, which however is really the trouble of a large one. She is obliged to go to other people's parties, sick or well, for fear of giving offence [sic], a thing more carefully avoided now than ever."3

In 1836 Susan Decatur finally sold the house on Lafayette Park to John Gadsby, a hotel owner and businessman. Although Decatur House remained an elegant setting for parties, the type of people who were entertained began to change. The French minister of the time wrote, "Some days ago I went to an evening party at Mr. Gadsby's. He is an old wretch who has made a fortune in the slave trade, which does not prevent Washington society from rushing to his house, and I should make my government very unpopular if I refused to associate with this kind of people. The gentleman's house is the most beautiful in the city, very well furnished, and perfect in the distribution of the rooms, but the society, my God!"4

After Gadsby's death in 1844, his widow rented out the house as Susan Decatur once had, and it continued to be the home of many illustrious people. During the Civil War the Federal Government took over Decatur House for use as office space. In 1871, General Edward Beale and his wife Mary bought Decatur House. They spent much time and money repairing damage done during the Civil War years, and remodeling the house to conform to the more ornate Victorian style of the Reconstruction years. Beale was a well-known character of his time. He carried the news of the California gold strike to Washington in 1848, fought with Kit Carson, scouted wagon roads and railroads in the West, and experimented with using camels as transport animals in the desert regions of the West.

In 1902, after the deaths of both General Beale and his wife, the house passed to their son Truxtun. Mrs. Beale became known as a generous and attentive hostess. Each year following the Christmas reception for the diplomatic corps at the White House, she held a party for the diplomats, and during Prohibition the Beale's well-stocked wine cellar outshone that in the White House. After her husband's death in 1936, Marie Beale remained at Decatur House for 20 more years. Upon her death in 1956, the Decatur House was bequeathed to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The building is now a historic house museum, but receptions and parties continue to be held there.

Questions for Reading 4

1. What happened to Decatur House after the death of Stephen Decatur?

2. Why did the French Minister disapprove of John Gadsby?

3. Why do you think the government took over several houses on Lafayette Park during the Civil War?

4. Why do you think so many important people wanted to live in or be entertained at Decatur House?

Reading 4 was adapted from Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Courtland VanDyke Hubbard, Historic Houses of George-Town & Washington City (Richmond, VA: Dietz Press, Incorporated, 1938); a study by Phillips & Oppermann, P.A., Initial Investigations of Decatur House, for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Washington D.C., Volume I Summary, 1991; and Excerpt from the Development Plan for the Decatur House, prepared for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, by Francis D. Lethbridge and Associates, 1980.

1As quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard, Historic Houses of George-Town & Washington City (Richmond, Virginia: The Dietz Press, Incorporated, 1938) p. 259.

2As quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard, p. 266.

3As quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard, p. 267.

4As quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard, p. 271.

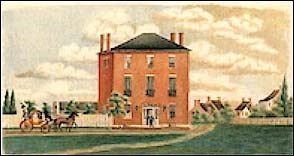

Drawing 2: 1822 watercolor of Decatur House

by E. Vaile.

(Decatur House Collection)

Photo 1: Decatur House, 1967.

Questions for Drawing 2 & Photo 1

1. Compare Drawing 2 and Photo 1. What differences can you detect?

2. How do surrounding buildings in both the drawing and photo affect your impression of the size of the house?

3. What can you learn about the time period by carefully studying the watercolor?

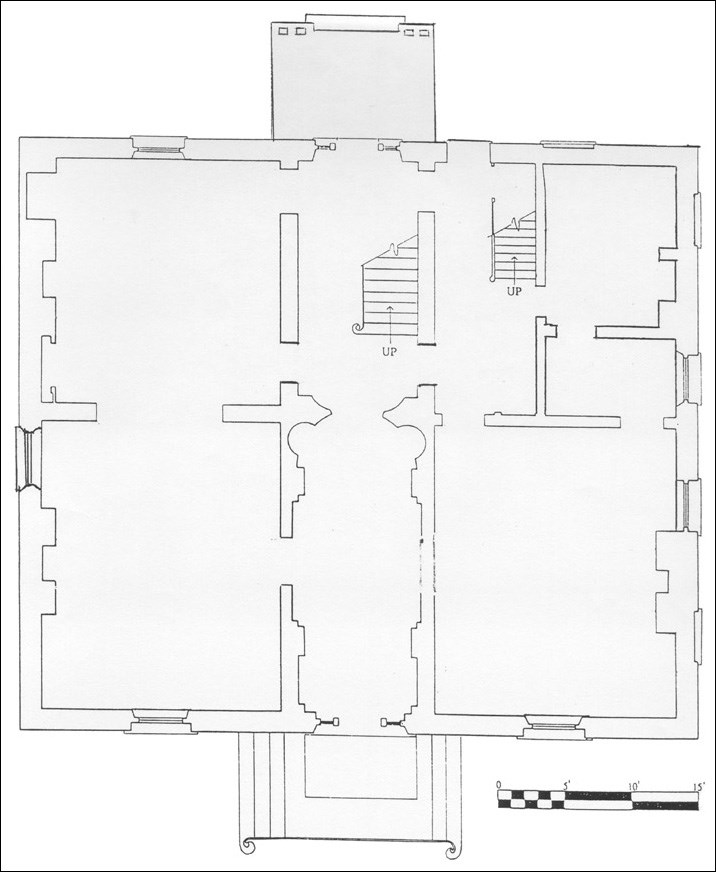

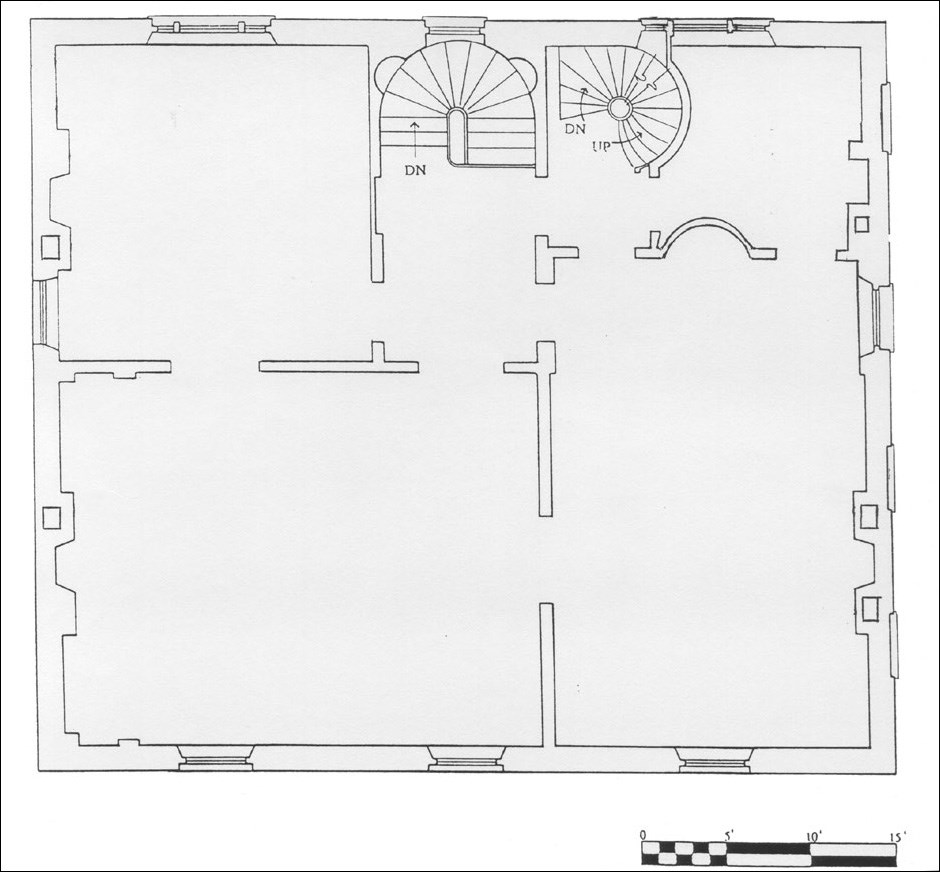

Drawing 3a: Decatur House, first floor.

These conjectural floor plans for the first and second floors of Decatur House, as built, are based on what is known about the use of the interior space. In Decatur's time, guests to large parties entered and processed through an impressive hall to a grand staircase, which led to the second floor rooms where large entertainments took place.

Questions for Drawing 3

1.What elements of the floor plans indicate that the house was designed with entertaining in mind? Why would this have been the case?

2. Use the scale to estimate the size of some of the rooms. How might the rooms on the first floor have been used during Decatur's occupancy?

Putting It All Together

It is unusual for so many famous people to have lived in a particular house. The combination of a beautiful structure and proximity to the White House made Decatur House a plum in the housing market of Washington, D.C. As students work through the following activities, have them keep in mind the importance that people of the 18th and 19th centuries placed on "proper" behavior in "proper" settings. Stress again the importance of social events in advancing a political or military career.

Activity 1: What Makes a Hero?

Explain to students that the dictionary defines a hero as a person who is noted for feats of courage or nobility of purpose, especially one who has risked or sacrificed his life. Stephen Decatur was considered a hero in his own time. Break the class into small groups to discuss the following questions.

-

Which deeds of Decatur characterized him as a hero?

-

What are some characteristics of people who become heroes? What characteristics did Decatur share with other people who have become heroes?

-

What benefits do heroes receive from their status?

-

Why do societies seem to need heroes?

Next, ask students to make a list of four or five present-day heroes who possess the characteristics the students have defined. Finally, hold a full class discussion to determine if there is general agreement as to appropriate answers to the questions among the class. What similarities and differences are there between Decatur and the contemporary heroes they identified? Have students use their U.S. history textbooks to determine other heroes of the 19th century and compare the deeds of those persons with Decatur's.

You might wish to expand the activity by having students conduct research on heroes in their own communities. What kinds of deeds made him or her a hero? Are there any places still standing in the community today that are associated with him or her? Have they been commemorated or memorialized in the community in some other way? How?

Activity 2: Conflict Resolution

Explain to students that conflict is a struggle between opposing forces. It can apply both to large-scale struggles such as battles or to a simple struggle within oneself. To resolve a conflict means to stop it, peacefully as by a friendly handshake and agreement to quarrel no more; by an all out battle between the opposing forces in which one becomes a victor; or by a decision by a judge or other arbiter who supports one side of the argument or forces both opponents to accept a compromise.

Have students use Readings 2 and 3 to review the conflict and the events that led up to the fateful duel between Stephen Decatur and James Barron. Then divide the class into two groups to hold a debate, with one side defending the actions of Decatur and the other side defending the actions of Barron. After the students are in groups, read them the following assignment:

Considering your knowledge of the Decatur/Barron feud, set up an oral argument based on statements from Reading 2 and Reading 3 that would defend your individual's position. Using your understanding of life in the 19th century, defend your individual's right to duel his opponent even though dueling was illegal and they were both well known and influential citizens.

Have students discuss their opinions and then choose a spokesperson to represent their group. Give each spokesperson five minutes to present their group's arguments to the class. Then allow 10 minutes for each spokesperson to consult with his group before presenting a rebuttal. The rebuttals should take three minutes and be given in the same order as the original presentations. Spokespersons should also be allowed two minutes for closing statements. If you hold a vote on who won the debate, be certain students consider the quality of preparation and presentation rather than their opinion on which man held "correct" views. Following the debate, have a full class discussion on the following issues:

-

Why did these two influential and powerful men find it necessary to risk their lives over a battle of honor?

-

Was the duel the appropriate ending to this conflict? In what other ways might the conflict have been resolved?

-

Do we see conflicts of this type in our society today? How are such conflicts resolved? Which methods are appropriate mechanisms for conflict resolution? Can you think of better mechanisms?

Activity 3: Access to Power

In today's world knowing the right people still provides the best access, and the party list of many Washington social events still acts as an indicator of whose career is moving forward, and who is out of favor. Even Americans who do not aspire to jobs in the upper echelons use social and personal contact as a way to find jobs or to influence people with political power to promote a cause they care deeply about. Tell students to keep these facts in mind as they complete this activity.

Ask students to choose a current issue or proposal that they would like to express an opinion about to the governor of their state. As an alternative, have them pretend that their governor is considering a budget that would dramatically reduce funding for local schools. Ask students to list various means of expressing support or disapproval of the issue or proposal, and of influencing the ultimate decision (petition, letter, fax, E-mail, telephone, the news media). Have students choose one of these means and either carry it out or write a description of why that particular means would be helpful in getting their opinion across to their legislator and the governor.

Next, have students consider whether a personal visit with the governor might be more effective. How would they go about getting an appointment with him or her? How would they present their concern in a typical 15-minute visit? What homework would they have to do to make sure they presented a good argument for their cause? Then have them suggest reasons why being located right next to the Governor's mansion might help them get the governor's attention. Discuss responses.

Ask students to name some political positions at the local level such as the school board chairman, mayor, or county supervisor. Would it be easier to arrange a personal visit with such individuals? Why? Do students think that their individual support or disapproval, or that of their parents, is likely to have more of an impact at the local or state level? Why?

The Decatur House--

Supplementary Resources

Decatur House: A Home of the Rich and Powerful examines the complicated rise and fall of a famous and rich naval hero. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of materials.

Decatur House

The Decatur House, a property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, is located in Washington, D.C. Visit the site's web pages for further information.

Navy: USS Decatur

Learn more about the U.S. Navy vessel that carries Commodore Stephen Decatur's name. Also included on the website is a short biography.

PBS: The American Experience

PBS offers a feature titled "The History of Dueling in America." Included is information on "Code Duello," 26 specific rules outlining all aspects of the duel.

Tags

- dueling

- presidents park

- washington d.c.

- dc history

- lafayette park

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- military wartime history

- federal

- american presidents

- america 250 nps

- 250

- founding fathers

- washington dc

- military history

- colonial

- colonial america

- war of 1812

- twhplp

- america 250